Medical Image of the Week: The Atoll Sign in Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

Wednesday, August 30, 2017 at 8:00AM

Wednesday, August 30, 2017 at 8:00AM

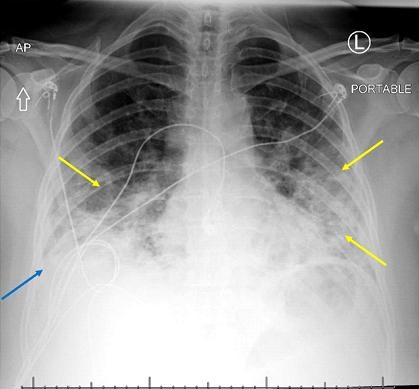

Figure 1. Portable chest X-ray shows bilateral airspace opacities (yellow arrows) and possible trace pleural effusion (blue arrow).

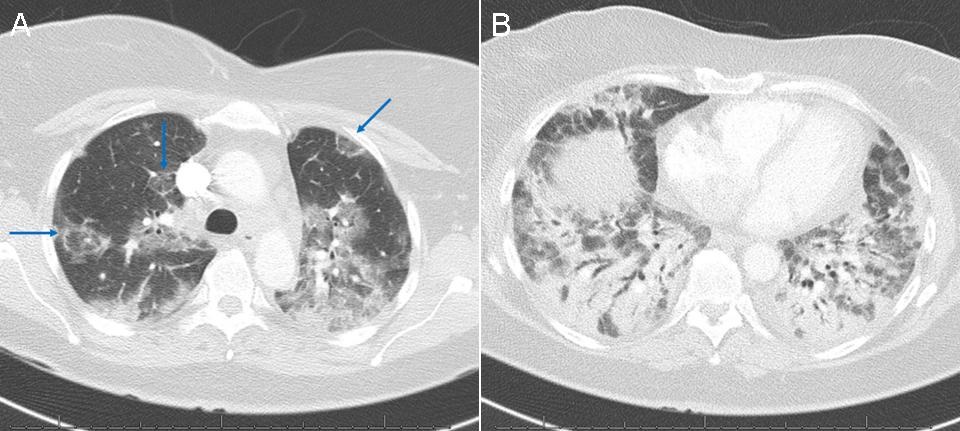

Figure 2. Computed tomography of the chest showing (A) patchy ground glass opacity in the upper lungs with additional scattered circular areas of opacity in a reverse halo configuration (blue arrows, atoll sign) and (B) extensive bibasilar consolidation with air bronchograms.

A 54-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with cough and worsening shortness of breath. Her cough began approximately 1 month prior to presentation, at which time she was diagnosed with pneumonia by her primary care physician based on a chest X-ray at an outside institution. She tried and failed courses of azithromycin, doxycycline, and levofloxacin.

The patient had an oxygen saturation of 55% and hyperpyrexia to 101.7 F in the emergency department. An initial chest X-ray was suggestive of moderate multifocal pneumonia with pleural effusion (Figure 1). Subsequent chest computed tomography (CT; Figure 2) revealed findings consistent with cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) including multiple upper lobe atoll signs. Infectious and autoimmune workups were negative and the patient experienced a rapid recovery with pulse steroids, providing further evidence for the diagnosis of COP.

CT is the best imaging modality for evaluation of potential COP. Features include consolidations and nodules, bronchial wall thickening or dilatation, and ground glass opacities (1). The atoll sign, consisting of a central ground glass opacity and surrounding consolidation which may also be called a reverse halo sign, is highly specific but not sensitive for organizing pneumonia (2). Definitive diagnosis requires lung biopsy, although the disease is often managed based on a presumptive diagnosis (3).

Joseph Frankl, BS1 and Veronica A. Arteaga, MD2

1University of Arizona College of Medicine and 2Department of Medical Imaging

Banner University Medical Center Tucson

Tucson, AZ USA

References

- Lee JW, Lee KS, Lee HY, Chung MP, Yi CA, Kim TS, Chung MJ. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: serial high-resolution CT findings in 22 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010 Oct;195(4):916-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidsen JR, Madsen HD, Laursen CB. Reversed halo sign in cryptogenic organising pneumonia. BMJ Case Rep. 2016 Feb 8;2016. pii: bcr2015213779. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley B, Branley HM, Egan JJ, et al. Interstitial lung disease guideline: the British Thoracic Society in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the Irish Thoracic Society. Thorax. 2008 Sep;63 Suppl 5:v1-58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Frankl J, Artega VA. Medical image of the week: the atoll sign in cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;15(2):92-3. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc100-17 PDF