May 2023 Medical Image of the Month: Methamphetamine Inhalation Leading to Cavitary Pneumonia and Pleural Complications

Tuesday, May 2, 2023 at 8:00AM

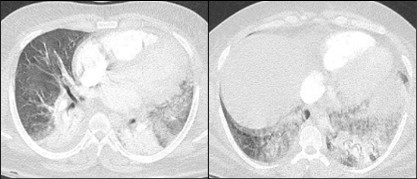

Tuesday, May 2, 2023 at 8:00AM  Figure 1. Two axial images from a thoracic CT angiogram with intravenous contrast upon admission demonstrates ground-glass opacities in the left upper and bilateral lower lobes.

Figure 1. Two axial images from a thoracic CT angiogram with intravenous contrast upon admission demonstrates ground-glass opacities in the left upper and bilateral lower lobes.

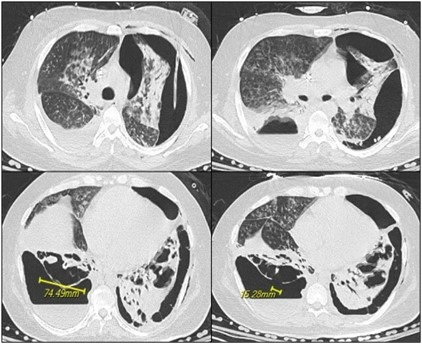

Figure 2. Axial images from noncontrast CT 19 days later show progression with necrosis and cavitation with areas of pleural dehiscence and loculated hydropneumothorax formation.

Figure 2. Axial images from noncontrast CT 19 days later show progression with necrosis and cavitation with areas of pleural dehiscence and loculated hydropneumothorax formation.

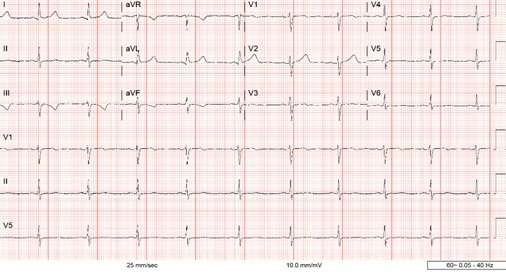

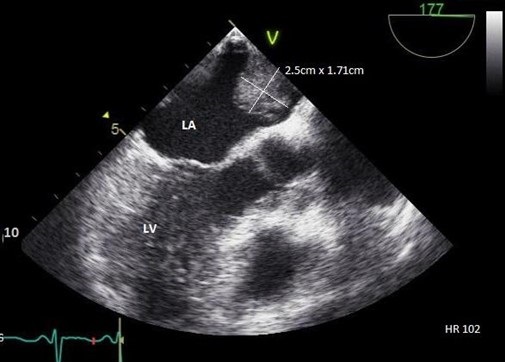

A 31-year-old man with a self-reported history significant for active methamphetamine and OxyContin use (last use of methamphetamine the same day with confirmation on urine drug screen) presented to the hospital with several hours of dyspnea. Having gone into cardiac arrest shortly after, he received several rounds of epinephrine and CPR and was intubated before spontaneous circulation returned. Bedside ultrasound revealed global hypokinesis with left ventricular ejection fraction of 10 to 15%, trivial pericardial effusion, and a moderate left pleural effusion. Chest CT (Figure 1) revealed segmental to subsegmental pulmonary emboli in the left lower lobe and ground-glass opacities in the left upper and bilateral lower lobes. He was treated as septic shock with Vancomycin and Cefepime, eventually speciating methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus in respiratory culture. Due to difficulty liberating the patient from the ventilator, he underwent tracheostomy tube placement. Chest x-ray on hospital day 18 showed a large left partially loculated hydropneumothorax, for which a left thoracostomy tube was placed. The next day repeat CT chest without contrast (Figure 2) showed persistent moderate left lung volume loss with tethering of the lateral and separate anterior margin of the left upper lobe to the costal pleural margin. A dense consolidation of the left lung base had progressed to developing irregular cavitary spaces with air-fluid level. There was a dehiscence of the cavitary space with the posterior left pleura. The right upper lobe showed extensive tree-in-bud ground-glass opacities and consolidation. The right lower lobe showed necrosis with intrapulmonary cavitary spaces/air-fluid levels. There was associated focal dehiscence of the parenchyma along the posterior cavity with the pleura. Patient had developed bilateral cavitary lung lesions with persistent bilateral hydropneumothoraces.

Typical findings of amphetamine induced lung injury can include ground-glass opacities as seen here. Worldwide prevalence of amphetamine use ranged between 0.3-1.3% for those aged 15-64 in 2009 (1). Crystal meth refers to the pure form of d-methamphetamine hydrochloride that can be smoked and inhaled as heated vapor as well. It can also be administered intravenously. Other amphetamines include MDMA, methyl methcathinone (commonly referred to as bath salts), and methylenedioxyamphetamine. Neural catecholamine reuptake is blocked, and neurotransmitter is expunged into the synaptic cleft. Additionally, serotonin and dopamine reuptake blockade and increased release take place.

With inhalation, there is higher percentage uptake, faster peak time, and slower clearance in the lungs compared to other organs as evidence by data from positron emission tomography. Time to peak concentration is the same between inhalation and intravenous use. Laboratories that produce amphetamines in the United States of America reduce L-ephedrine or D-pseudoephedrine either over red phosphorous with hydrochloric acid or with liquid ammonia and lithium. Therefore, they pose risks of contamination. Red phosphorous is flammable and causes smoke inhalation injury. Other solvents used also contribute to respiratory illness including pulmonary edema and mucous membranes irritation (1).

Typical respiratory symptoms from illicit drug use, including amphetamine use, include dyspnea, cough, dark sputum, and chest pain. Mechanisms include toxic effects on the respiratory system, coronary artery constriction, and impaired coronary artery oxygen delivery leading to chest pain. Dyspnea is a primarily a result of ventilation-perfusion mismatch from vasospasm. Bronchospasm is precipitated by airway mucosal irritation. Mucosal ulceration and burns as well as subsequent diffuse alveolar capillary injury lead to hemoptysis. Cardiogenic pulmonary edema stems from the same causes of chest pain as well as acute hypertension and myocardial ischemia. Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema is a result of alveolar epithelial and endothelial damage.

As compared to cocaine, amphetamines have lower rates of barotrauma including pneumothorax, pneumopericardium, and pneumomediastinum, however these are still significant. There have been reports of MDMA-related epidural pneumatosis and retropharyngeal emphysema (1). Air dissects along fascial planes when alveoli are injured and travels up the pulmonary vascular sheath into the mediastinum, pericardium, and between the parietal and visceral layers. When inhaled, coughing, and performing a Valsalva maneuver predispose the patient to this complication (2). Additionally, pneumothorax is more common with exertion shortly after consumption. Attempts at intravenous administration along the chest, supraclavicular regions, and internal jugular veins increase risk of pneumothorax (3). Hemothorax and pseudoaneurysm have been documented as well (2).

Kia Ghiassi DO1, Colin Jenkins MD1, Prateek Juneja DO2

1,2University of California Riverside, Riverside, CA USA

2Inspira Health, Vineland, NJ USA

References

- Tseng W, Sutter ME, Albertson TE. Stimulants and the lung : review of literature. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2014 Feb;46(1):82-100. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen ET, Silva CI, Souza CA, Müller NL. Pulmonary complications of illicit drug use: differential diagnosis based on CT findings. J Thorac Imaging. 2007 May;22(2):199-206. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotway MB, Marder SR, Hanks DK, et al. Thoracic complications of illicit drug use: an organ system approach. Radiographics. 2002 Oct;22 Spec No:S119-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]