Robert A Raschke MD MS

robert.raschke@bannerhealth.com

Professor of Clinical Medicine

Banner Good Samaritan Regional Medical Center

Phoenix, Arizona

Abstract

We report the case of a patient who suffered fatal cardiopulmonary effects of a mobile blood clot adherent to the internal orifice of her tracheostomy tube. We believe the clot acted as a one-way valve, leading to dynamic hyperinflation and elevated intrinsic positive end expiratory pressure (iPEEP). This complication of a tracheostomy tube was suggested by clinical findings of expiratory wheezing, hypotension, increasing peak inspiratory pressure, and unusual but distinctive radiographic findings. Confirmation of one-way tracheostomy tube obstruction was difficult, even with a bronchoscopic examination. When this diagnosis is suspected, tracheostomy tube exchange should be rapidly performed.

Case Report

The patient was a 59-year old woman who had undergone elective colostomy for symptomatic colonic atony. The patient developed a post-operative anastomotic leak, and septic shock. Despite surgical intervention and broad-spectrum antibiotics, acute respiratory distress syndrome ensued, necessitating prolonged mechanical ventilation. On the 29th day of admission, an 8.0 DCT Shiley tracheostomy tube was placed in an open procedure.

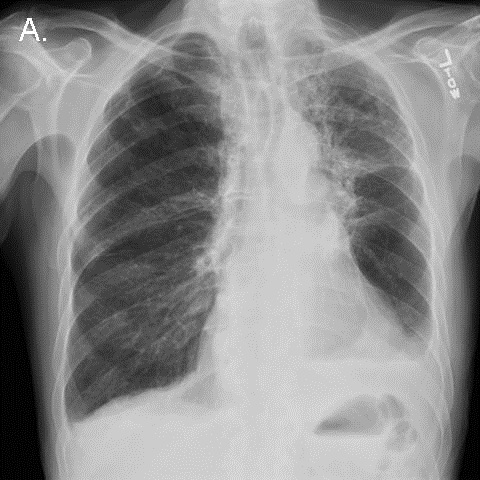

On day 33, a chest radiograph demonstrated persistent diffuse pulmonary infiltrates that had not significantly improved over the preceding 3 weeks (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Portable chest x-ray the morning before the code arrest.

Minor bleeding was noted from the tracheostomy tube. Shortly thereafter, peak inspiratory pressures suddenly rose to the point that adequate tidal volumes could not be delivered by a mechanical ventilator. The inner cannula of the tracheostomy tube was removed. A suction catheter passed easily though the external cannula lumen, and a small amount of blood was suctioned out. However, attempts to bag-ventilate the patient became progressively more difficult. The patient's head and neck became cyanotic and mottled, and a pulse could no longer be detected. Advanced cardiac life support was initiated. Examination was significant for pan-expiratory wheezes throughout the thorax interrupted only by strenuous attempts to at bag-mask inspiration. The trachea was midline, and there was no subcutaneous crepitus. The abdomen was soft. A bronchoscope passed through the tracheostomy tube easily, revealing a widely patent trachea and major airways. Bag ventilation transiently improved, cyanosis resolved, and a blood pressure of 150/85 was briefly obtained. Inhaled albuterol and intravenous corticosteroids were administered. A chest x-ray was performed (Figure 2).

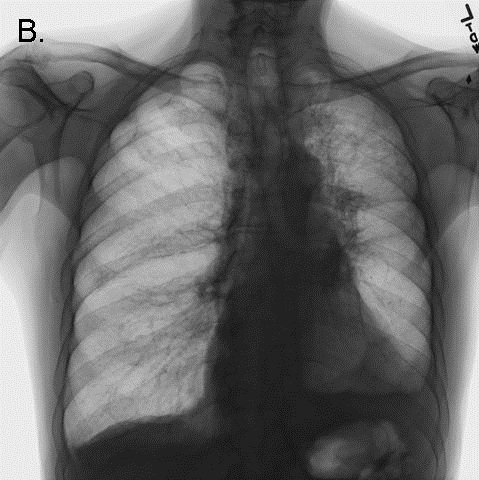

Figure 2. CXR performed during the code arrest, showing flattening of the diaphragms, and acute narrowing of the cardiac silhouette/vascular pedicle, and acute clearing of pulmonary infiltrates, consistent with hyperinflation.

Bag-ventilation became progressively more difficult, and the patient once more became hypotensive and cyanotic. The bronchoscope again passed easily through the tracheostomy and revealed the same findings as before. Needle thoracostomy was considered to treat possible pneumothorax, but the chest x-ray returned to the bedside demonstrated no evidence of barotrauma. The radiograph demonstrated striking improvement in pulmonary edema, a reduction in the size of the cardiac silhouette and vascular pedicle, and flattening of the diaphragms (see Figure 2 - note: the large radio-opacity overlying the mid-portion of the left lung is the shadow of an adherent transcutaneous pacing pad, not a pneumothorax). Further resuscitative efforts were unsuccessful.

The possibility of tracheostomy dysfunction was re-considered at some length in a postmortem debriefing. We concluded that the most likely explanation for the patient's clinical and radiological findings was dynamic hyperventilation and hemodynamic consequences of severe iPEEP induced by a dysfunction of the tracheostomy tube.

Autopsy Findings

The tracheostomy tube was left in place, and the pathologist carefully dissected the trachea open from the carina in a caudal direction to expose the internal tip of the tracheostomy tube in-situ. A blood clot was found that nearly completely occluded the internal orifice of the tube (Figure 3, Panel A). The clot swung out of the way of some IV tubing passed inward through the external orifice of the tracheostomy tube, but swung shut again when the IV tube was removed, like a trap door (Figure 3, Panel B).

Figure 3. Longitudinal view of the open tracheal lumen at autopsy. Orientation: the left side of the figure is rostral. In panel A, the distal orifice of the tracheostomy tube can be seen to be nearly completely obstructed by a thrombus (black arrow). In panel B, the thrombus (black arrow) can be seen to be pushed aside by the passage of a plastic catheter (white arrow),

This clot appeared to function as a one-way valve, allowing inward passage of air, suction catheters, and a bronchoscope, but severely obstructing exhalation. We reasoned that such an obstruction could lead to wheezing and dynamic hyperinflation, and could explain the clinical and radiographic findings. Ultimately, severe iPEEP compromised cardiac preload, leading to pulselessness and death.

No other cause for the patient's clinical syndrome was found - specifically, the patient had no antecedent history of asthma, had received no new medications on the day of the arrest, nor had any dermatological findings suggestive of anaphylaxis. The autopsy failed to reveal pulmonary embolism, mucous plugging, pneumothorax, or any histological evidence of asthma.

Discussion

We are not the first to report dynamic hyperinflation as a complication of uni-directional tracheostomy tube obstruction (1). Several experienced clinicians at our institution recall dealing with this entity before, therefore, we suspect that it is not as rare as the paucity of clinical reports suggests. We felt that the clinical, radiological and postmortem findings in our case are sufficiently interesting, and the danger of missing this diagnosis sufficiently great, to warrant a brief review.

Other types of tracheostomy tube dysfunction can cause high airway pressure and hypotension. Bi-directional tube obstruction from blood, dried secretions, or balloon hyperinflation is the most common (2,3). Barotrauma related to tracheostomy tubes may occur when they become displaced into the soft tissues of the neck, or into the pleural space, or when the cutaneous tracheostomy wound is sutured in an overly constrictive manner (4).

We learned three important lessons from this unfortunate case:

- Clinical and radiographic findings can suggest the diagnosis of expiratory tracheostomy obstruction in a patient ventilated through a tracheostomy tube. The key clinical findings are: expiratory wheezing, hypotension, increasing iPEEP, and increasing peak inspiratory pressure. Unexpected radiographic improvement in pulmonary edema may suggest the presence of occult iPEEP if it is not directly measured.

- The diagnosis of unidirectional obstruction of a tracheostomy tube can be difficult to confirm. The easy passage of suction catheters, or a bronchoscope, does not rule it out. If bronchoscopy is performed emergently, the internal lumen and internal orifice of the tracheostomy tube should be examined with extreme deliberation. This can be difficult during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. If visualized, the potential detriment of small mobile clots should not be under-estimated.

- Alternative airway access should be immediately pursued in patients with tracheostomy tubes who are difficult to ventilate. In dire clinical situations, the best diagnostic test might be to simply see if the patient improves with a new airway. If the tracheostomy tract is likely to be mature (> 5 days old), the tracheostomy tube can simply be exchanged. If the tract is immature, or if tube displacement is suspected, oral laryngoscopic intubation should be performed immediately. The tracheostomy tube may need to be pulled out in order to accommodate the endotracheal tube in the trachea. Either of these actions would likely have saved our patient's life.

References

- Timmus HH. Tracheostomy: An Overview of implications, management, and morbidity. Advances in Surgery 1973;7:199-233.

- Saini S, Taxak S, Singh MR. Tracheostomy tube obstruction caused by an overinflated cuff. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;122:768-9.

- Rowe BH, Rampton J, Bota GW. Life-threatening luminal obstruction due to mucous plugging in chronic tracheostomies: three case reports and a review of the literature. J Emerg Med 1996;14:565-7.

- Tayal VS. Tracheostomies. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1994;12:707-27.

The author reports no financial support and no conflict of interest for this publication.

Reference as: Raschke RA. Fatal dynamic hyperinflation secondary to a blood clot acting as a one-way valve at the internal orifice of a tracheostomy tube. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2012;5:256-61. PDF

Saturday, February 2, 2013 at 6:56AM

Saturday, February 2, 2013 at 6:56AM