December 2023 Medical Image of the Month: Metastatic Pulmonary Calcifications in End-Stage Renal Disease

Saturday, December 2, 2023 at 8:00AM

Saturday, December 2, 2023 at 8:00AM

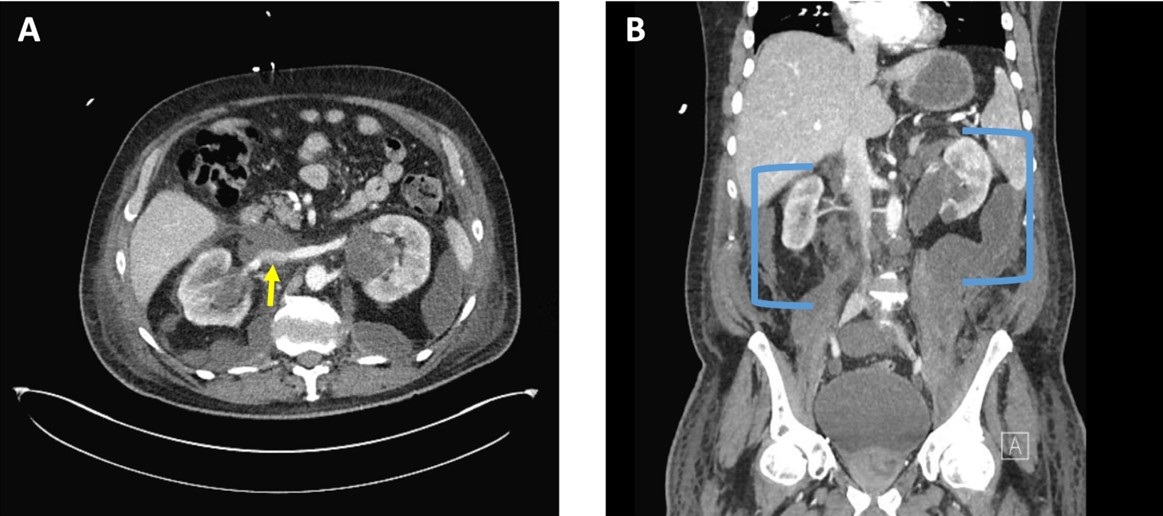

Figure 1. Pulmonary function testing results for the patient demonstrate severe restriction with a reduced diffusion capacity with a corrected DLCO 50% of predicted and FVC 45% of predicted. To view Figure 1 in an enlarged, separate window click here.

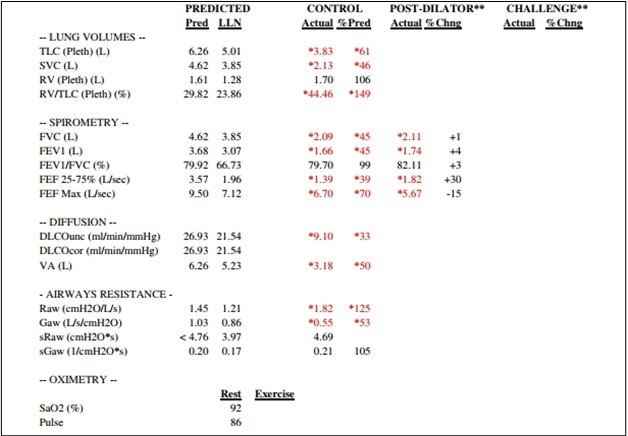

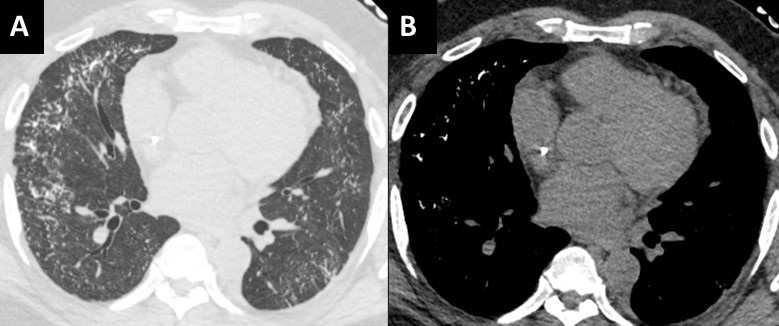

Figure 2. Unenhanced chest CT images in the axial plane reconstructed with lung (A) and soft tissue (B) display settings. There are innumerable small solid pulmonary nodules with a peripheral distribution, some subpleural sparing, and architectural distortion (A). On soft tissues windows (B) the fact that the nodules are calcified are well-appreciated in the anterior and lateral right mid-lung. To view Figure 2 in a separate, enlarged window click here.

Figure 2. Unenhanced chest CT images in the axial plane reconstructed with lung (A) and soft tissue (B) display settings. There are innumerable small solid pulmonary nodules with a peripheral distribution, some subpleural sparing, and architectural distortion (A). On soft tissues windows (B) the fact that the nodules are calcified are well-appreciated in the anterior and lateral right mid-lung. To view Figure 2 in a separate, enlarged window click here.

A 51-year-old African-American man with medical history of obesity (BMI 36) and hypertension was seen in pulmonary consultation for preoperative evaluation of kidney transplantation. End-Stage renal disease (ESRD) was diagnosed 7 years before evaluation secondary to resistant hypertension. The patient has been on hemodialysis since then. The patient was on carvedilol, hydralazine, losartan, and calcitriol. He had prescribed sevelamer and prednisone, but he was not taking them. His main symptoms were 3-year chronic dyspnea on exertion and mild morning cough productive of small amounts of clear sputum. He has had no chest pain, wheezes, hemoptysis, fevers, or dizziness. He had trace lower extremity edema. He worked as a forklift operator. He has had no relevant exposures and was a lifetime nonsmoker.

The patient was diagnosed with cryptogenic organizing pneumonia 5 years ago and was on prednisone taper with subjective improvement of symptoms. He has not had lung function testing or biopsies done at that time. He was maintained on 3L oxygen with activity to targets oxygen saturation of 90%. On examination VS: BP 216/100, HR 94, temperature 36.7 °C, SpO2 88 % RA. He was not in respiratory distress. Chest auscultation: symmetrical breath sounds, no added sounds. Examination of the heart, abdomen and rest of the systems were normal. He had trace bilateral pedal edema and clubbing in all digits.

Figure 1 shows his most recent pulmonary function test illustrating a severe restrictive defect with reduced diffusion capacity. Echocardiogram showed ejection fraction of 54%, mild left ventricular hypertrophy and mild diastolic dysfunction. Representative slices of his most recent computed tomography (CT) of the chest are shown in figure 2 and demonstrate multiple scattered small, solid, and calcified pulmonary nodules.

Pulmonary calcifications can either be secondary to hypercalcemia from benign or malignant causes {1}. Such calcification would occur in normal lung tissue due to elevated calcium-phosphate product and is termed metastatic {2,3}. It is thought to occur with higher concentrations of free hydrogen ions, especially in less ventilated areas (West zone 3) with lower pH (more acidotic), leading to calcium-magnesium phosphate compounds (whitlockite-like). Dystrophic calcification on the other hand develops secondary to injury from granulomatous diseases, infections or inherited pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis {4}.

Most cases of metastatic pulmonary calcification are due to ESRD-related hypercalcemia {2}. Most patients are asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally. Some patients may have non-productive cough, progressive dyspnea, and hypoxia. Lung function testing could show normal or restrictive ventilatory defects, often with impaired diffusion of carbon monoxide. CT scans are diagnostic (Figure 2) and show distinctive diffuse calcifications (sometimes solid and sometimes manifesting as centrilobular ground glass). Bone scintigraphy using technetium-99 diphosphonate scanning would show these calcifications along other parts of the body affected with reported higher sensitivity compared to standard x-ray {5}.

Management is geared towards controlling levels of calcium through phosphate binders, dialysis dosing, and/or parathyroidectomy. Our patient was ultimately evaluated for combined lung/kidney transplantation due to his severe restrictive pulmonary defects.

Abdelmohaymin Abdalla MD1, Clinton Jokerst MD2, Umesh Goswami MD1

Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine1

Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix, AZ USA

Department of Radiology2

Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix, AZ USA

References

- Kaltreider HB, Baum GL, Bogaty G, McCoy MD, Tucker M. So-called "metastatic" calcification of the lung. Am J Med. 1969 Feb;46(2):188-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conger JD, Hammond WS, Alfrey AC, Contiguglia SR, Stanford RE, Huffer WE. Pulmonary calcification in chronic dialysis patients. Clinical and pathologic studies. Ann Intern Med. 1975 Sep;83(3):330-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzela DC, Huffer WE, Conger JD, Winter SD, Hammond WS. Soft tissue calcification in chronic dialysis patients. Am J Pathol. 1977 Feb;86(2):403-24. [PubMed]

- Chan ED, Morales DV, Welsh CH, McDermott MT, Schwarz MI. Calcium deposition with or without bone formation in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 Jun 15;165(12):1654-69. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faubert PF, Shapiro WB, Porush JG, Chou SY, Gross JM, Bondi E, Gomez-Leon G. Pulmonary calcification in hemodialyzed patients detected by technetium-99m diphosphonate scanning. Kidney Int. 1980 Jul;18(1):95-102. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Abdalla A, Jokerst C, Goswami U. December 2023 Medical Image of the Month: Metastatic Pulmonary Calcifications in End-Stage Renal Disease. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care Sleep. 2023;27(6):67-69. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpccs049-23 PDF