September 2023 Medical Image of the Month: Aspergillus Presenting as a Pulmonary Nodule in an Immunocompetent Patient

Saturday, September 2, 2023 at 8:00AM

Saturday, September 2, 2023 at 8:00AM

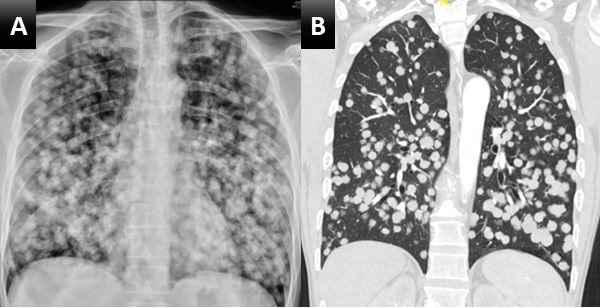

Figure 1. Chest CT showing 11 x10 mm nodule in the anterior segment of the left upper lobe in the background of emphysematous and basal sub segmental atelectatic changes.

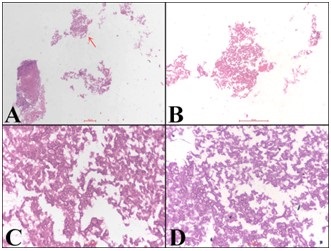

Figure 2. Lung biopsy low power (A) showing chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the interstitium along with a collection of fungus (arrow) (H&E: x40). Fungus with an area of necrosis (B) (H&E: x100). Numerous thin, narrow-angle, and branching hyphae with septa morphologically consistent with Aspergillus (C) (H&E: x400). Collection of Aspergillus (D). (Periodic acid–Schiff stain: x400).

Figure 2. Lung biopsy low power (A) showing chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the interstitium along with a collection of fungus (arrow) (H&E: x40). Fungus with an area of necrosis (B) (H&E: x100). Numerous thin, narrow-angle, and branching hyphae with septa morphologically consistent with Aspergillus (C) (H&E: x400). Collection of Aspergillus (D). (Periodic acid–Schiff stain: x400).

A 32-year-old nonsmoking woman presented with complaints of recurrent hemoptysis for 5 months and dyspnea on exertion for 1 month. She denied any history of fever, cough, or COVID infection. She has hypothyroidism controlled on thyroxine 25mcg. During the evaluation, she was found to have an enhancing solitary pulmonary nodule (11 x 10 x 9mm) in the anterior segment of the left upper lobe (Figure 1). The patient was given a course of oral antibiotics (amoxicillin /clavulanic acid) and supportive treatment for hemoptysis. Sputum for Ziehl–Neelsen stain and cartridge based nucleic acid amplification test (CBNAAT) was negative. CT- guided biopsy of the nodule was performed. Histopathology showed fungal organisms which were thin, septate with acute angle branching and focal necrotic areas, morphologically consistent with Aspergillus (Figure 2). Serum-specific IgG against aspergillus antigen was normal. The patient was started on oral itraconazole 200mg BID. Follow-up after 1 month showed both symptomatic and radiological improvement. Repeat chest CT showed a significant decrease in size of the nodule.

There is a large spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. From this spectrum, pulmonary nodules are a less common manifestation of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA), especially in immunocompetent individuals. Aspergillus nodules are defined as small, round, discrete, and focal opacities on chest imaging. It can be further classified on basis of internal cavitation (i.e., non-cavitary nodules and cavitary nodules). Differentiating these nodules from other lung pathology may be difficult on CT findings alone and may demand further investigation like image-guided needle aspiration cytology or biopsy, blood investigations like serum Aspergillus precipitin IgG antibody and/or serum Aspergillus galactomannan. Delay in diagnoses may lead to persistence of pulmonary symptoms, and cavitation of the nodule. This entity has a favorable prognosis if managed accordingly. Although there is data regarding surgical management of aspergillus nodules, but data regarding the benefits of anti-fungal therapy in the same is limited.

Diagnosing aspergillus nodules in an immunocompetent individual is a challenge to all pulmonologists. Literature shows limited case reports and small case series on CPA presenting as non-cavitating SPN on radiology. Usually, in such cases, the diagnosis is made following removal or biopsy of the nodule(s), presuming it to be malignant. Patients diagnosed with Aspergillus nodules can’t be differentiated from lung malignant conditions based on demographics, which are usually similar. In the largest case series of Aspergillus nodules done by Muldoon EG et al. (6), 33 patients were reviewed constituting less than 10 % of the cohort of patients with CPA. In a study done by Kang et al. (4) 77% of patients with aspergillus nodules were symptomatic and the most common symptom reported was hemoptysis. Similarly in our case hemoptysis was the chief complaint of the patient. Our patient is a woman and non-smoker similar to previous case reports and series.

In the current guidelines, the detection of serum Aspergillus precipitin IgG antibody is a key diagnostic criterion for CPA. Literature is unclear if the presence of Aspergillus IgG antibody could be considered a supportive finding in the making the diagnosis of Aspergillus nodules. Similarly, in our case also serum specific IgG against Aspergillus fumigatus was negative. Azoles are the primary treatment option in all subtypes of CPA including aspergillus nodule. Our patient also showed disease regression during itraconazole treatment. Another option for management is surgical, though it is associated with significant postoperative complications and recurrence of disease at other sites and must be reserved for selected patients.

Dr. Deependra Kumar Rai, Dr. Priya Sharma, Dr. Vatsal Bhushan Gupta

Department of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine

AIIMS Patna, Bihar, India

References

- Kosmidis C, Denning DW. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Thorax. 2015 Mar;70(3):270-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008 Mar;246(3):697-722. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee SH, Lee BJ, Jung DY, Kim JH, Sohn DS, Shin JW, Kim JY, Park IW, Choi BW. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes of pulmonary aspergilloma. Korean J Intern Med. 2004 Mar;19(1):38-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang N, Park J, Jhun BW. Clinical Characteristics and Treatment Outcomes of Pathologically Confirmed Aspergillus Nodules. J Clin Med. 2020 Jul 10;9(7):2185. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda M, Nagashima A, Haro A, Saitoh G. Aspergilloma mimicking a lung cancer. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(8):690-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muldoon EG, Sharman A, Page I, Bishop P, Denning DW. Aspergillus nodules; another presentation of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis. BMC Pulm Med. 2016 Aug 18;16(1):123. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning DW, Cadranel J, Beigelman-Aubry C, et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur Respir J. 2016 Jan;47(1):45-68. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limper AH, Knox KS, Sarosi GA, et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: Treatment of fungal infections in adult pulmonary and critical care patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Jan 1;183(1):96-128. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godet C, Philippe B, Laurent F, Cadranel J. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Respiration. 2014;88(2):162-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kousha M, Tadi R, Soubani AO. Pulmonary aspergillosis: a clinical review. Eur Respir Rev. 2011 Sep 1;20(121):156-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]