Stella C. Pak, MD

Andrew Kobalka, BS

Yaseen Alastal, MD

Scott Varga, MD

Department of Medicine

University of Toledo Medical Center

Toledo, OH, USA 43614

Abstract

The present study aims to integrate the growing body of evidence on the possible association between the severity of chronic inflammatory respiratory disorders (CIRDs) and the frequency of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Eight studies were analyzed to assess the correlation between the severity of CIRDs and the incidence of VTE. Our results suggest that there is no significant increased risk of VTE in patients with severe CIRD compared to mild or moderate CIRD, OR=0.92 (95% CI 0.59 – 1.43; I2 = 74%). Further studies are indicated to explore this possible association. Gaining a better understanding of the VTE risk for patients with CIRDs will enable clinicians to provide better individualized risk management and preventive care.

Introduction

In this age of rapid developments in health care, pioneering attempts are being made to improve the management of chronic inflammatory respiratory disorders (CIRDs). Despite significant public health efforts over the past few decades, the prevalence of CIRDs continues to rise. Common types of CIRDs include asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), and bronchiectasis. Bronchiectasis, a pathologic description of lung damage characterized by inflamed and dilated thick-walled bronchi (1), is most commonly caused by respiratory infections or other pro-inflammatory events such as toxin inhalation (2). Patients with recurrent airway damage due to impaired mucociliary clearance secondary to genetic alterations commonly develop bronchiectasis (2); the overall percentage of bronchiectasis patients with cystic fibrosis is approximately 5-6% (3,4).

There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that individuals with CIRDs are at increased risk for developing venous thromboembolism (5-7). Multiple studies indicate one tenth of patients with acute COPD exacerbation develop VTE (5). Despite this, the possible correlation between CIRD severity and VTE risk has not been sufficiently explored in the literature.

Two plausible mechanisms for VTE in CIRDs are inflammation-induced thrombosis and steroid-induced thrombosis. Inflammation-induced thrombosis involves interaction among activated platelets, leukocytes, and endothelial cells promoting excessive procoagulant activity of endothelium (8). Steroids are also postulated to induce prothrombotic state by increasing the serum concentration of von Willebrand factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (9).

Subtypes of VTE including PE and DVT can lead to significant chronic complications. Nearly 50% of patients who have DVT develop post-thrombotic syndrome within 2 years despite being on anticoagulant therapy (10). Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, which is reported to occur in 0.5 to 4% of patients with history of PE, can lead to right-sided heart failure, exercise intolerance, and dyspnea (11). A recent study showed that pulmonary embolism led to higher mortality in patients with severe COPD compared to general population (12). Episodes of VTE and their sequelae complicate the management of patients with CIRDs. Considering this burden from VTE, preventive measures with risk stratification are needed.

Assessing the correlation between the severity of CIRDs and the risk for VTE would improve the quality of care by allowing accurate risk assessment and proper risk management. Furthermore, demystifying this association would give patients agency in their own care. A recent study showed that 84% of activated protein C-resistant women on combined oral contraceptives changed their method of contraception after finding out that they had increased risk for VTE, and a majority were pleased to learn of their APC resistance status (13). Understanding the correlation between the severity of CIRDs and VTE would help clinicians provide better education and lifestyle advice to patients with CIRDs.

The goal of this study is to assess the correlation between the severity of CIRDs (including COPD, asthma, and cystic fibrosis) and the frequency of VTE. Gaining a better understanding of these correlations will offer significant clinical benefits and facilitate better individualized care for patients with varying severity of CIRDs.

Methods

Search Strategy

English language studies published up to March, 10th 2017 were located via a search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and Web of Science. Key search terms included the following: “CIRD,” “COPD,” “Asthma,” “CF,” “DVT,” “PE,” and “VTE.” Appendix 1 describes specific search terms used in each database.

Inclusion Criteria

The criteria for inclusion required studies: 1) to include adult patients with CIRDs with different severity based on objective index or score system 2) to include the frequency of VTE among participants 3) to be prospective or retrospective observational studies, and 4) to report raw number of patients found to have VTE in different severity group.

Exclusion Criteria

The following criteria were used to exclude studies from this review: 1) Use of subjective measure in severity determination 2) Case study 3) Pediatrics population 4) Non-English literature.

Meta-Analysis

A random effects meta-analysis was performed to determine the association between the severity of CIRDs and VTE risk. The random model was applied to derive the summary estimate. Proportions were calculated using logit transformation (log-odds). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 value. The funnel plot was constructed to detect and adjust for potential publication bias. All statistical tests were two-sided and p-values of less than 0.05 were statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the Review Manager 5.3.5 program (Cochrane, London, UK).

Results

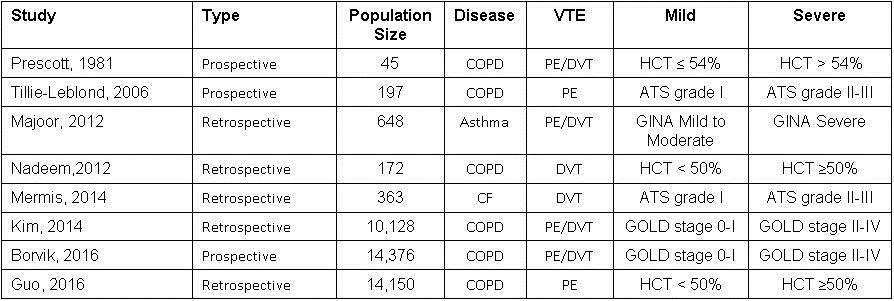

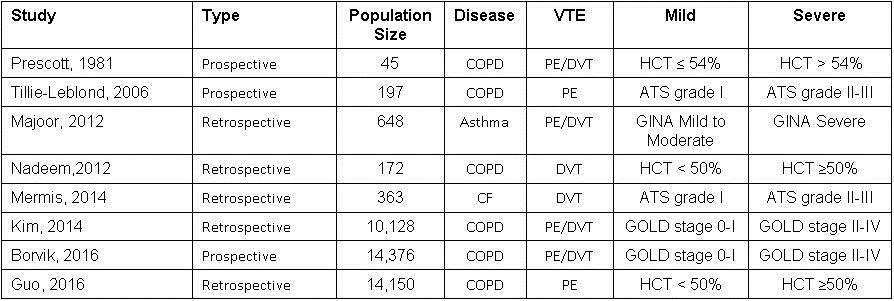

A total of 8 trials (23,899 patients) were included for analysis (14-21). Table 1 describes the characteristics of included studies.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

HCT: hematocrit, ATS: American Thoracic Society, GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, PE: pulmonary embolism, DVT: deep venous thromboembolism, GINA: Global Initiative for Asthma Classification.

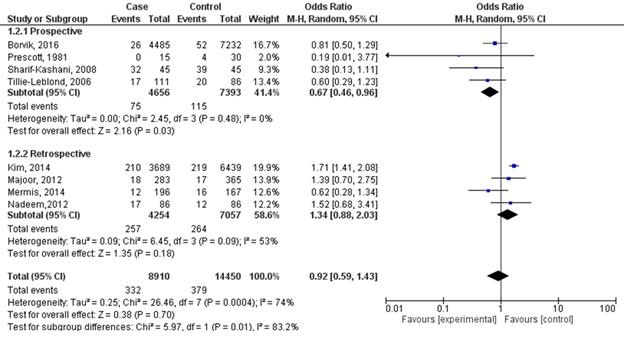

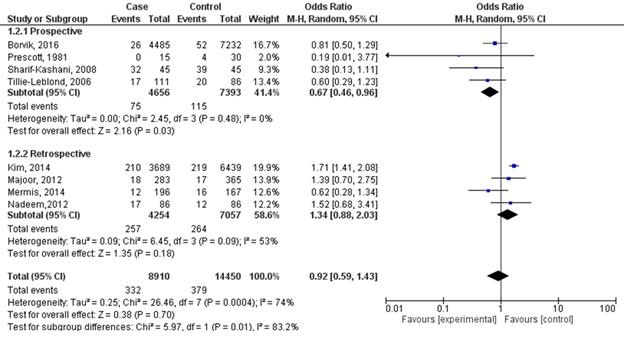

The odds ratio of DVT frequency for people with severe COPD compared to those with moderate or mild COPD was 0.92 (95% CI 0.59 – 1.43; I2 = 74%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Forest plot of studies on chronic inflammatory respiratory disorders and venous thromboembolism with study-type subanalysis.

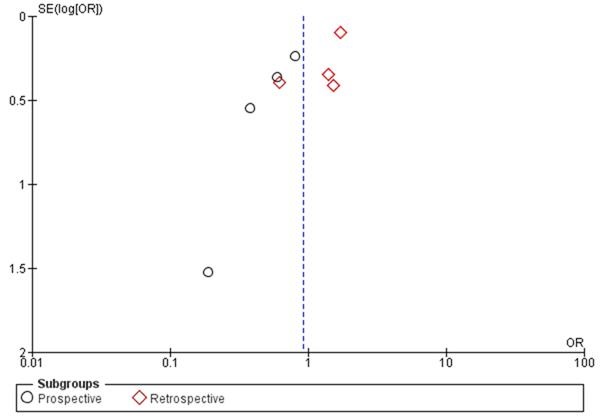

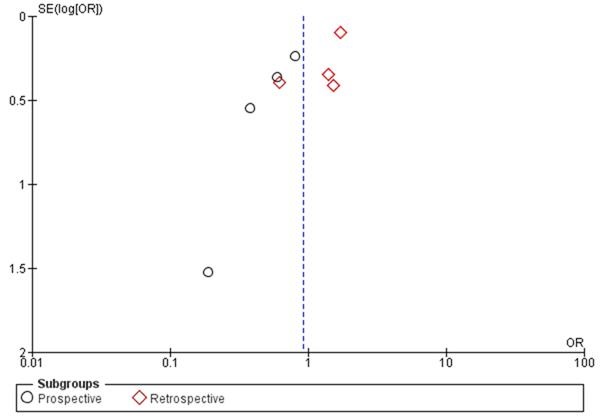

In subgroup analysis, the odds ratio for prospective studies was 0.67 (95% CI 0.46 – 0.96; I2 = 0%). On the other hand, subgroup analysis from retrospective studies showed odds ratio of 1.34 (95% CI 0.88 – 2.03; I2 = 53%). Funnel plot suggests that publication bias minimally influenced retrospective studies (Figure 2). However, the plot suggests that mild publication bias exists among the included prospective studies.

Figure 2. Funnel plot of studies on chronic inflammatory respiratory disorders and venous thromboembolism with study-type subanalysis.

Discussion

Our results indicate no significant association between the severity of CIRDs and VTE risk. Several limiting factors, including substantial variation in the measures of disease severity, may have influenced the final result. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) staging system, American Thoracic Society (ATS) grading system, and the presence of polycythemia were used as disease severity measures in patients with COPD. Global Initiative for Asthma Classification (GINA) system measured severity of asthma, and ATS grading system measured severity of cystic fibrosis. We tried to use the random effect model to compensate for this heterogeneity. Confounding factors such as smoking status, exercise level, BMI, quality of health care, and ethnicity could also have contributed to the development of VTE in the studied population. Finally, a wide variation in cohort size across studies could have confounded the results.

The outcome of subanalysis on prospective studies was contradictory to those of retrospective studies. The retrospective study design, the researchers tend to have limited control over consistency and accuracy. Major limitation for prospective studies is the loss to follow-up associated with relatively long follow-up period (22). These limitations may have contributed to these contradictory outcomes from subanalyses.

The presence of polycythemia was used as a severity indicator for COPD in three of the studies, while GOLD stages II-IV was used in two of the studies. The decision to use polycythemia as an indicator of COPD severity was based upon the finding that more than 70% of COPD patients with polycythemia are in GOLD stage III or IV (21). However, as not every patient with polycythemia is in GOLD stage III or IV, this novel measure might not be strongly correlated enough with disease severity.

While large-scale prospective and retrospective studies assessing COPD severity and VTE risk have been undertaken, the multiple systems for grading COPD severity limits our ability to compare studies. A uniform disease severity grading system is needed to compare studies in this way.

In summary, our results indicate no significant association between the severity of CIRDs and VTE risk. Further exploration of the relationship between disease severity in patients with CIRDs and risk of VTE is necessary to improve risk stratification system and preventive care for this patient population. We hope the present work helps foster subsequent research on this possible association.

References

- Pasteur MC, Helliwell SM, Houghton SJ, Webb SC, Foweraker JE, Coulden RA, Flower CD, Bilton D, Keogan MT. An investigation into causative factors in patients with bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 Oct, 162(4 Pt 1): 1277-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athanazio R. Airway disease: similarities and differences between asthma, COPD and bronchiectasis. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012;67:1335-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verra F, Escudier E, Bignon J, Pinchon MC, Boucherat M, Bernaudin JF, de Cremoux H. Inherited factors in diffuse bronchiectasis in the adult: a prospective study. Eur. Respir. J. 1991 Sep; 4(8)937-44. [PubMed]

- Girodon E, Cazeneuve C, Lebargy F, Chinet T, Costes B, Ghanem N, Martin J, Lemay S, Scheid P, Housset B, Bignon J, Goossens M. CFTR gene mutations in adults with disseminated bronchiectasis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 1997 May-Jun; 5(3):149-55. [PubMed]

- Ambrosetti M, Ageno W, Spanevello A, Salerno M, Pedretti RF. Prevalence and prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Thromb Res. 2003;112: 203-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi G, Favaloro EJ. Allergy and venous thromboembolism: a casual or causative association. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2016;42: 63-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemoto CM. Venous thromboembolism in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47: 105-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksu K, Donmez A, Keser G. Inflammation-induced thrombosis: mechanisms, disease associations and management. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18: 1478-93. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuijver DJ, Majoor CJ, van Zaane B, Souverein PC, de Boer A, Dekkers OM, Büller HR, Gerdes VEA. Use of oral glucocorticoids and the risk of pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Chest. 2013;143: 1337-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin MJ, Moore HM, Rudarakanchana N, Gohel M, Davies AH. Post-thrombotic syndrome: a clinical review. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11: 795-805. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klok FA, van der Hulle T, den Exter PL, Lankeit M, Huisman MV, Konstantinides S. The post-PE syndrome: a new concept for chronic complications of pulmonary embolism. Blood Rev. 2014;28: 221-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahloul M, Chaari A, Tounsi A, et al. Incidence and impact outcome of pulmonary embolism in critically ill patients with severe exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Clin Respir J. 2015;9: 270-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindqvist PG, Dahlback B. Reactions to awareness of activated protein C resistance carriership: a descriptive study of 270 women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82: 467-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott SM, Richards KL, Tikoff G, Armstrong JD, Jr., Shigeoka JW. Venous thromboembolism in decompensated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;123: 32-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillie-Leblond I, Marquette CH, Perez T, Scherpereel A, Zanetti C, Tonnel AB, Remy-Jardin M. Pulmonary embolism in patients with unexplained exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence and risk factors. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144: 390-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majoor CJ, Kamphuisen PW, Zwinderman AH, Ten Brinke A, Amelink M, Rijssenbeek-Nouwens L, et al. Risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in asthma. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(3):655-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeem O, Gui J, Ornstein DL. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with secondary polycythemia. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2013;19:363-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mermis JD, Strom JC, Greenwood JP, Low DM, He J, Stites SW, Simpson SQ. Quality improvement initiative to reduce deep vein thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central catheters in adults with cystic fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11: 1404-10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim V, Goel N, Gangar J, Zhao H, Ciccolella DE, Silverman EK, Crapo JD, Criner GJ; and the COPD Gene Investigators. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2014;1 :239-49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Børvik T, Brækkan SK, Enga K, Schirmer H, Brodin EE, Melbye H, Hansen JB. COPD and risk of venous thromboembolism and mortality in a general population. Eur Respir J. 2016;47: 473-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo L, Chughtai AR, Jiang H, Gao L, Yang Y, Yang Y, Liu Y, Xie Z, Li W. Relationship between polycythemia and in-hospital mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with low-risk pulmonary embolism. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8: 3119-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song JW, Chung KC. Observational studies: cohort and case-control studies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:2234-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Pak SC, Kobalka A, Alastal Y, Varga S. Correlation between the severity of chronic inflammatory respiratory disorders and the frequency of venous thromboembolism: meta-analysis. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;14(6):285-91. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc035-17 PDF

Friday, September 1, 2017 at 8:00AM

Friday, September 1, 2017 at 8:00AM