April 2023 Medical Image of the Month: Atrial Myxoma in the setting of Raynaud’s Phenomenon: Early Echocardiography and Management of Thrombotic Disease

Sunday, April 2, 2023 at 8:00AM

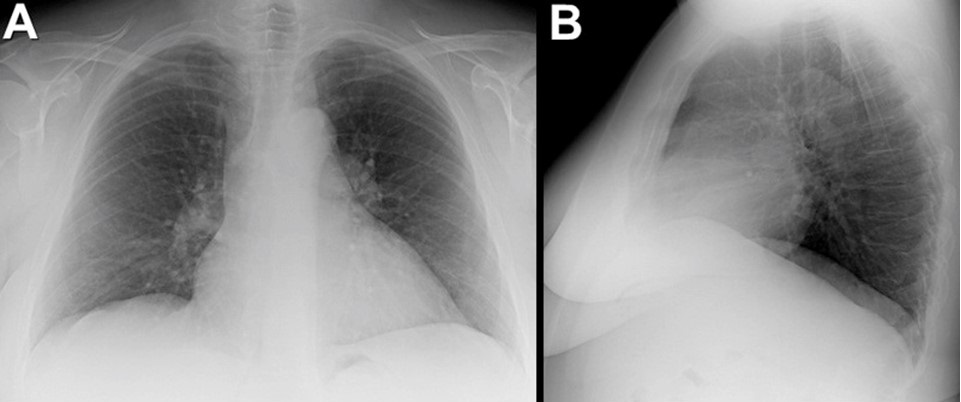

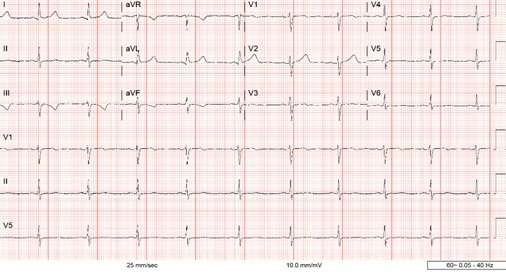

Sunday, April 2, 2023 at 8:00AM  Figure 1. ECG demonstrating sinus bradycardia and T-wave inversion in lead III and aVF.

Figure 1. ECG demonstrating sinus bradycardia and T-wave inversion in lead III and aVF.

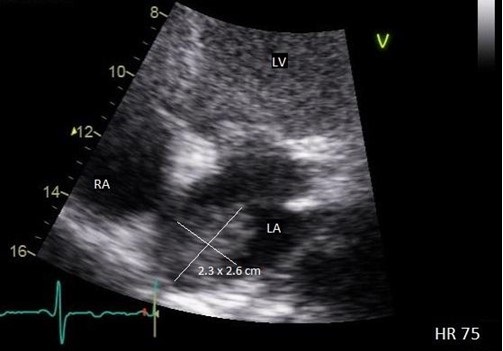

Figure 2. Transthoracic echo apical four-chamber view (zoomed) demonstrating 2.3 x 2.6 cm echogenic mass of the left atrium. LV = left ventricle. RA = right atrium. LA = left atrium.

Figure 2. Transthoracic echo apical four-chamber view (zoomed) demonstrating 2.3 x 2.6 cm echogenic mass of the left atrium. LV = left ventricle. RA = right atrium. LA = left atrium.

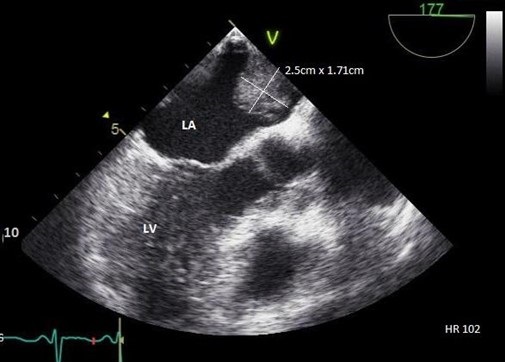

Figure 3. Transesophageal echo, midesophageal long axis view demonstrating 2.5 x 1.71 cm echogenic left atrial mass attached to upper dome of the left atrium. LA = left atrium. LV = left ventricle.

Figure 3. Transesophageal echo, midesophageal long axis view demonstrating 2.5 x 1.71 cm echogenic left atrial mass attached to upper dome of the left atrium. LA = left atrium. LV = left ventricle.

A 43-year-old woman presents to the Emergency Department (ED) with right-sided weakness and numbness for several hours. Medical history is significant for Raynaud’s Phenomenon (RP), initially presenting six months prior to presentation, manifesting as intermittent episodes of painless discoloration of multiple fingers. Cardiac exam was unremarkable with regular rhythm and no discernable murmur. Neurological exam demonstrated right arm pronator drift. Other examination findings were unremarkable. Labs demonstrated a troponin of 0.00 ng/mL, C-reactive protein of 2.28 mg/dL, and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 40 mm/hr. The electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated sinus bradycardia and notable for T-wave inversion in lead III and aVF, but without any ST-segment deviations (Figure 1). Magnetic Resonance Imagining (MRI) of the brain demonstrated acute ischemic left frontal, left parietal, and right parietal infarcts along with mild subcortical left parietal infarct, concerning for venous or watershed distal embolic arterial infarct. MRI Angiogram of the brain showing diminutive bilateral, lateral transverse dural venous sinuses, consistent with thrombus. The patient’s neurological deficits resolved within five hours of ED arrival. Given the background diagnoses of RP and new thrombosis, a complete autoimmune and hypercoagulability workup was pursued and was otherwise negative.

As part of acute stroke work-up, the patient also underwent transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) with a bubble study, which was significant for left atrial (LA) echogenic intracardiac structure attached to the superior part of the LA (Figure 2). Transesophageal Echocardiogram (TEE) was performed which demonstrated a large, 2.5 x 1.71 cm mass, consistent with an atrial myxoma, not appearing to involve the interatrial septum but instead thought to originate from the upper dome of the atrium immediately adjacent to the pulmonary veins (Figure 3). Patient was also evaluated by neurology and started on anticoagulation with parental continuous unfractionated heparin infusion given the dural venous sinus thrombosis and a possible hypercoagulable state due to the underlying myxoma. Patient underwent surgical resection of the atrial mass Histopathological examination of the resected mass was consistent with the diagnosis of atrial myxoma.

Although atrial myxomas are the most common primary cardiac tumor, clinical presentation ranges from incidental imaging findings to profound life-threading cardiovascular manifestations (1). This range of presentation is closely associated with size, mobility, and location (2). Pinede et al. studied 112 cases of atrial myxomas and reported that signs of cardiac obstruction were the primary manifestation of LA myxoma. Approximately, 67% of patients presented with signs of cardiac obstruction, such as heart failure, syncope, or myocardial infarction, while embolic signs were only present in 29% of patients. Systemic signs including fever and weight loss were only reported in 34% of patients with only 5% of patients having associated connective tissue disease (3). Rarely, RP has been described as the primary presenting symptom of atrial myxoma (4,5), underscoring the utility of maintaining a high degree of suspicion when symptomatology coexists.

RP is a vascular response to stress or cold temperature that appears as color changes in the digits (6). Although primary RP has no known underlying etiology, it is more commonly seen in female patients with a history of smoking, migraine headaches, and cardiovascular disease (6). This is in contrast to secondary RP, which presents in patient with an underlying autoimmune rheumatic disease including, but not limited, to Systemic Sclerosis, Mixed Connective Tissue Disease, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Sjogren’s Syndrome, and hematologic disorders such as Cryoglobulinemia, Cold Agglutinins Disease, and Paraproteinemia (7).

Atrial myxoma may rarely make its initial appearance under the guise of RP (4). This phenomenon is likely attributable to overproduction of IL-6 by the myxoma (9-11). Our patient presented with RP six months prior to her presentation to the ED with right-sided weakness and numbness and a complete autoimmune and hypercoagulability workup was negative; this may suggest that the underlying pathophysiology of her RP is the associated overproduction of IL-6 by the atrial myxoma.

TTE may be considered in the initial diagnostic evaluation of a patient presenting with RP without additional findings suggestive of secondary etiologies. Given that myxomas are typically localized within the atrial lumen, transthoracic echocardiography is a highly sensitive modality for diagnosis, whereas CT and MRI may also help in diagnostics in uncertain cases. Once suspicion of a cardiac myxoma has been supported by imaging modalities, surgical removal of the tumor should be performed as soon as possible due to the risk of myxoma associated embolic episodes (5). Post intervention, long term prognosis is excellent with an approximated 5% rate of recurrence (3). Long-term follow-up with serial TTE are recommended, particularly in younger patients (3) but there is no specific guideline regarding the frequency of TTE surveillance post atrial myxoma resection.

Ali A. Mahdi MD, Chris Allahverdian MD, Vishal Patel MD, Serap Sobnosky MD

Dignity Health, St. Mary Medical Center, Department of Internal Medicine, Long Beach, CA

References

- Roberts WC. Primary and secondary neoplasms of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1997 Sep 1;80(5):671-82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaher MF, Bajaj S, Habib M, Doss E, Habib M, Bikkina M, Shamoon F, Hoyek WN. A giant left atrial myxoma. Case Rep Med. 2014;2014:819052. [CrossRef]

- Pinede L, Duhaut P, Loire R. Clinical presentation of left atrial cardiac myxoma. A series of 112 consecutive cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001 May;80(3):159-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skanse B, Berg No, Westfelt L. Atrial myxoma with Raynaud's phenomenon as the initial symptom. Acta Med Scand. 1959 Jul 25;164:321-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1996 Jan 1;77(1):107. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulla, M. C., & Alungal, J. (2015). Atrial myxoma in a primigravida presenting as Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheumatology Reports, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Prete M, Favoino E, Giacomelli R, et al. Evaluation of the influence of social, demographic, environmental, work-related factors and/or lifestyle habits on Raynaud's phenomenon: a case-control study. Clin Exp Med. 2020 Feb;20(1):31-37. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khouri C, Blaise S, Carpentier P, Villier C, Cracowski JL, Roustit M. Drug-induced Raynaud's phenomenon: beyond β-adrenoceptor blockers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016 Jul;82(1):6-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jourdan M, Bataille R, Seguin J, Zhang XG, Chaptal PA, Klein B. Constitutive production of interleukin-6 and immunologic features in cardiac myxomas. Arthritis Rheum. 1990 Mar;33(3):398-402. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saji T, Yanagawa E, Matsuura H, Yamamoto S, Ishikita T, Matsuo N, Yoshirwara K, Takanashi Y. Increased serum interleukin-6 in cardiac myxoma. Am Heart J. 1991 Aug;122(2):579-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parissis JT, Mentzikof D, Georgopoulou M, Gikopoulos M, Kanapitsas A, Merkouris K, Kefalas C. Correlation of interleukin-6 gene expression to immunologic features in patients with cardiac myxomas. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1996 Aug;16(8):589-93. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Mahdi AA, Allahverdian C, Patel V, Sobnosky S. April 2023 Medical Image of the Month: Atrial Myxoma in the setting of Raynaud’s Phenomenon: Early Echocardiography and Management of Thrombotic Disease. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care Sleep. 2023;26(4):56-58. doi:https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpccs006-23 PDF