Maintaining Medical Competence

Sunday, November 18, 2012 at 5:32PM

Sunday, November 18, 2012 at 5:32PM “I am free, no matter what rules surround me…because I know that I alone am morally responsible for everything I do.”― Robert A. Heinlein

I recently renewed my Arizona medical license and meet all the requirements. I far exceed the required CME hours and have no Medical Board actions, removal of hospital privileges, lawsuits, or felonies. None of the bad things are likely since I have not seen patients since July 1, 2011 and I no longer have hospital privileges. However, this caused me to pause when I came to the question of “Actively practicing”? A quick check of the status of several who do not see patients but are administrators, retired or full time editors of other medical journals revealed they were all listed as “active”. I guess that “medical journalism” is probably as much a medical activity as “administrative medicine” which is recognized by the Arizona Medical Board. This got me to thinking about competence and the Medical Board’s obligation to ensure competent physicians.

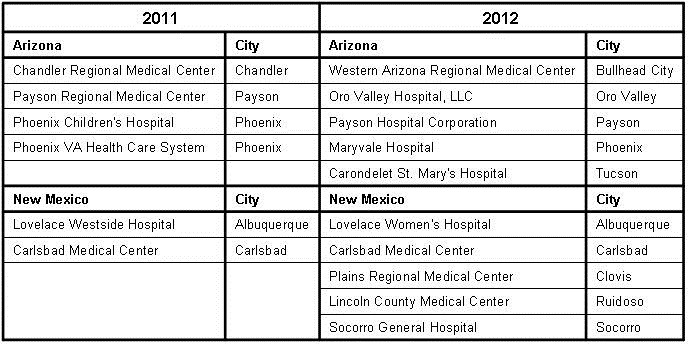

Medical boards focused on preventing the unlicensed practice of medicine by “quacks” and “charlatans” in the first half of the Twentieth Century. The Boards evolved over time to promote higher standards for undergraduate medical education; require assessment of knowledge and skills to qualify for initial licensure; and develop and enforce standards for professional practice. Beginning with New Mexico in 1971, nearly all state medical boards require a prescribed number of continued medical education (CME) hours with Colorado being a notable exception. Colorado’s lack of CME requirements goes against the recent trends. In 2010 the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) House of Delegates voted to adopt a framework for maintenance of licensure to address concerns among policymakers and regulators (1). The FSMB’s framework contains three components: 1. reflective self assessment; 2. assessment of knowledge and skills; and 3. performance in practice.

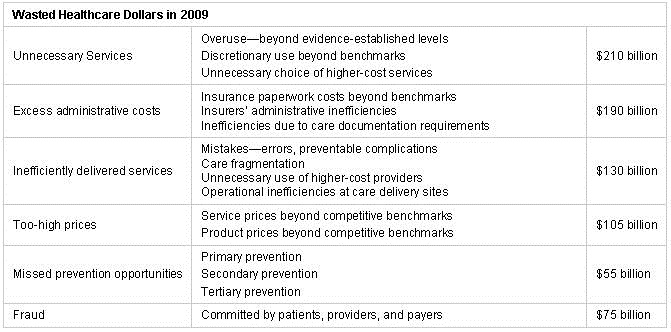

Self-reflection has long been a mainstay of good medical practice. However, the requirement is vague and most evidence suggests that physicians are not very good at it (2). Assessment and reassessment of knowledge and skills has been present in most medical specialty and subspecialty boards for some time. Furthermore, actively practicing physicians are required to undergo periodic peer review and reapplication for hospital privileges. Further testing and assessment seems costly and largely unneeded. However, medical licensure is above all about seeing and treating patients. What is new is FSMB’s recognition of the importance of active medical practice in determining medical competence. In many instances, policymakers such as chiefs of staff, hospital board members, administrators or members of guideline writing committees have been non- or very limited practicing physicians. Their decisions have often been fundamentally flawed. Quality has been frequently politically defined rather than patient centered and evidence based. In too many cases, hastily adopted guidelines are proven wrong and even potentially dangerous to patients (3).

A physician who directs care should be subject to the “Continued Competency Rule” which is used in Colorado (4). This rule requires that a physician, “if not having engaged in active practice for two or more years…be able to demonstrate continued competency”. It needs to be recognized that those who meet this standard are only competent in their own area of practice. For example, a pulmonary and critical care physician has no business directing neurosurgical care or formulating orthopedic guidelines. Administrative medicine, and for that matter, medical journalism, would do not meet this standard of competency since neither involves taking responsibility for the care of patients. The requirement for physician administrators to be really active in the practice of medicine may be one key to improved medical care and competence. At least it should make them think about directing care or mandating a guideline that they, themselves have to follow.

Richard A. Robbins, MD*

References

- Chaudhry HJ, Talmage LA, Alguire PC, Cain FE, Waters S, Rhyne JA. Maintenance of licensure: supporting a physician's commitment to lifelong learning. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:287-9.

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA 2006;296:1094-102.

- Robbins RA, Thomas AR, Raschke RA. Guidelines, recommendations and improvement in healthcare. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2011;2:34-37.

- http://www.dora.state.co.us/medical/ (accessed 11/5/12).

* The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Arizona, New Mexico or Colorado Thoracic Societies.

Reference as: Robbins RA. Maintaining medical competence. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2012;5:266-7. PDF