Medical Image of the Week: Mucous Plugs Forming Airway Casts

Wednesday, December 13, 2017 at 8:00AM

Wednesday, December 13, 2017 at 8:00AM

Figure 1. Bronchoscopic view of the mucous plug.

Figure 2. Cast removed with cryo-adhesion probe.

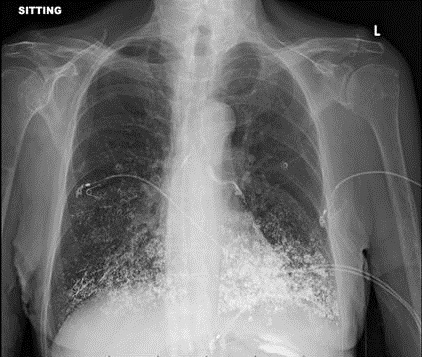

A 64 -year-old man with a recent diagnosis of acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) on chemotherapy presented with acute hypoxic respiratory failure, multifocal pneumonia, neutropenic fever and septic shock. The patient was intubated and required vasopressors for septic shock. His blood and sputum cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chest computed tomography demonstrated extensive consolidation of the left lung mainly the left lower lobe with extensive endobronchial mucus plugs. The patient underwent bronchoscopy after noninvasive measures failed to resolve the left lung atelectasis. After multiple attempts to retrieve the mucus plugs (Figure 1) with suction failed, a cryo-adhesion probe was used to freeze and retrieve the mucus plug. The plug formed a cast taking the shape of the airway (Figure 2).

Flexible bronchoscopy is warranted in patients who have persistent atelectasis or pneumonia that is either of unknown cause or suspected of being due to airway obstruction (1). The use of cryo-adhesion and extraction has been particularly useful in the management of airway obstruction caused by foreign bodies especially mucus plugs and blood clots that are not easily extracted by more standard means such as suction or forceps (2).

Huthayfa Ateeli, MBBS and Cameron Hypes MD, MPH

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, Sleep and Allergy Medicine

University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ USA

References

- Feinsilver SH, Fein AM, Niederman MS, Schultz DE, Faegenburg DH. Utility of fiberoptic bronchoscopy in nonresolving pneumonia. Chest. 1990 Dec;98(6):1322-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strausz J, Bolliger CT. Interventional pulmonology. Sheffield: European Respiratory Society; 2010: 165.

Cite as: Ateeli H, Hypes C. Medical image of the week: mucous plugs forming ariway casts. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;15(6):278-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc147-17 PDF