Medical Image of the Month: Incarcerated Morgagni Hernia

Saturday, March 2, 2019 at 8:00AM

Saturday, March 2, 2019 at 8:00AM

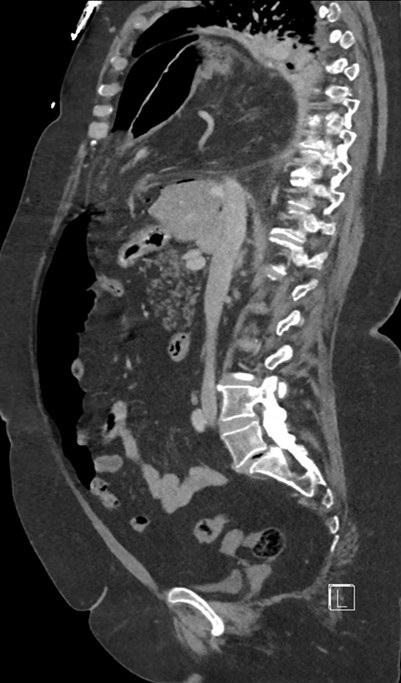

Figure 1. Lateral view of abdominal-thoracic CT in soft tissue windows.

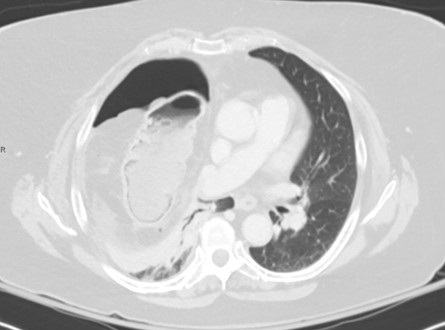

Figure 2. Coronal view of thoracic CT scan in lung windows.

A Morgagni hernia is a congenital diaphragmatic hernia in which abdominal viscera herniate into the thorax via a defect within an anterior attachment of the diaphragm. As with any bowel-containing hernia, the most feared complication is strangulation with subsequent bowel necrosis. In the present case, a 67-year-old woman presented with a five-day history of acute onset and progressively worsening upper abdominal pain and inability to tolerate oral intake, associated with nausea, vomiting, and mild shortness of breath. A CT revealed a large defect in the right hemidiaphragm consistent with a Morgagni hernia with herniation of the omentum, vessels, and a segment of transverse colon (Figure 1). Findings of bowel ischemia were observed, including (a) pneumatosis intestinalis, seen as cystic foci of air lining the bowel wall, and (b) fluid and fat-stranding adjacent to the affected bowel (Figure 2). Evidence of bowel wall perforation include large volume free air adjacent to the bowel in the right hemithorax and within the abdomen (Figures 1 and 2). Bowel ischemia and necrosis can occur with any hernia and requires prompt diagnosis and management.

Samandip Hothi MD1 and Viral Patel MD2

1Department of Medicine, Division of Internal Medicine and 2Department of Medical Imaging

University of Arizona College of Medicine-Tucson

Tucson, AZ USA

References

- Arora S, Haji A, Ng P. Adult Morgagni Hernia: The Need for Clinical Awareness, Early Diagnosis and Prompt Surgical Intervention. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008 Nov;90(8):694-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly JQ. The Rigler Sign. Radiology. 2003;228(3):706-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan TB, Nguyen DN, Tran CD, Maheshwary RK, Mickus TJ. Morgagni Hernia Causing Incarcerated Bowel and Contributing to Cardiac Arrest. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2018 Jul 31. pii: S0363-0188(18)30181-6. [CrossRef]

Cite as: Hothi S, Patel V. Medical image of the month: Incarcerated Morgagni hernia. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2019;18:59-60. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc001-19 PDF