Medical Image of the Week: Diffuse Pulmonary Ossification

Friday, August 2, 2019 at 8:00AM

Friday, August 2, 2019 at 8:00AM

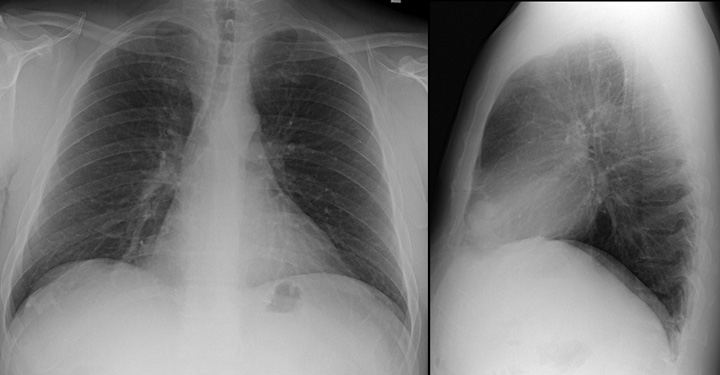

Figure 1. Scout view from a high-resolution CT (HRCT) in this patient, demonstrating predominantly peripheral coarse interstitial thickening, with architectural distortion. Multiple calcific densities are associated with the interstitial abnormality.

Figure 2. A: High resolution CT axial image, 1 mm slice thickness, “lung windows”, bone algorithm. (Window width, 2500 HU; level, 500 H). Extensive peripheral/subpleural predominant reticulation and superimposed net-like, branching, and highly attenuating structures (dendriform configuration) are nicely depicted. Some coexisting less than 4 mm nodules are deposited predominantly in the areas of reticulation. B: Corresponding mediastinal window.

An 84-year-old man with a twelve-year history of interstitial lung disease with indolent course was referred for a new oxygen requirement. He had previously been diagnosed with usual interstitial pneumonia associated with occupational exposures. Over the previous six-months he became breathless with minimal activity. During this interval he had lost nearly 40 pounds. He had worked in uranium mining and had a mere four-pack-year smoking history. In his free time, he was an artisan and engaged in woodworking, metal craft and stonework. He was hypoxic with exertion and notably cachectic. His clinic exam was significant for grade 1 clubbing and soft inspiratory crackles that were audible at the bilateral bases. Pulmonary function testing demonstrated a restrictive ventilatory defect with severe reduction in diffusion capacity. A chest radiograph was followed by high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) with representative images shown in Figures 1 and 2. A diagnosis of diffuse pulmonary ossification (DPO) associated with UIP was made.

Pulmonary ossification indicates bone tissue formation; this in contrast to the deposition of calcium salts in pulmonary calcification. The pathogenesis is uncertain as most patients have no derangements in serum calcium and phosphorus levels. Transforming growth factor-β, implicated in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, is also thought to stimulate chondrocytes and osteoblasts in DPO. Other associated chemokines include bone morphogenic protein, and interleukins 1 and 4.

Patients with DPO may be minimally symptomatic or have significant disease to the level of respiratory failure. The diagnosis is most often made by a surgical biopsy or at the time of autopsy. Nodular and dendriform histologic types are described; the latter of which develops in areas of interstitial fibrosis. The nodular form often follows longstanding pulmonary venous congestion from cardiovascular disorders. Chest radiography is insensitive for diagnosis and may only demonstrate an interstitial pattern. Calcification is generally only seen once HRCT is obtained. 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate (Tc-MDP) nuclear medicine scanning will also detect the presence of pulmonary ossification. Imaging-wise, the differential diagnosis for DPO, is restricted. Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis could potentially be confused with DPO. The intra-alveolar accumulation of innumerable minute calculi called microliths are generally much smaller, usually less than 2 mm, with a uniform size and distribution throughout the lungs (‘sandpaper” appearance). At a later phase the number and volume of the calcific deposits increases and becomes more granular. The distribution follows the interlobular septa or bronchovascular bundles and can be confused with DPO. Previous granulomatous disease may have a somewhat similar appearance. However, the density per area unit of the calcific deposits tends to be much less, and the distribution is more random and not necessarily associated with underlying abnormal/ fibrosing tissue. There is a strong association between DPO and IPF, when compared with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. This may improve diagnostic specificity in patients with IPF.

Therapy with calcium binding agents, chelation, and corticosteroids has been disappointing, and there is currently no proven treatment.

Steven Sears DO1, Bhupinder Natt MD1, and Diana Palacio MD2

1Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, Allergy and Sleep and 2 Department of Medical Imaging

University of Arizona College of Medicine. Tucson, AZ USA

References

- Chai JL, Patz EF. CT of the lung: patterns of calcification and other high-attenuation abnormalities. AJR AM J Roegenol. 194;152:1063-6.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried ED, Godwin TA. Extensive diffuse pulmonary ossification. Chest. 1992;102:1614-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan ED, Morales DV, Welsh CH, McDermott MT, Schwarz MI. Calcium deposition with or without bone formation in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1654-69. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz MI, King TE. Interstitial lung disease 3rd ed. Hamilton, Ontario: B.C Decker, 1998.

- Fernández-Bussy S, Labarca G, Pires Y, Díaz JC, Caviedes I. Dendriform pulmonary ossification. Respir Care. 2015 Apr;60(4):e64-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egashira R, Jacob J, Kokosi MA, Brun AL, Rice A, Nicholson AG, Wells AU, Hansell DM. Diffuse pulmonary ossification in fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: prevalence and associations. Radiology. 2017 Jul;284(1):255-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellana G, Castellana G, Gentile M, Castellana R, Resta O. Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis: review of the 1022 cases reported worldwide. Eur Respir Rev. 2015 Dec;24(138):607-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Sears S, Natt B, Palacio D. Medical image of the week: diffuse pulmonary ossification. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2019;19(2):65-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc028-19 PDF