Medical Image of the Week: Carcinoid at the Carina

Wednesday, June 10, 2015 at 8:00AM

Wednesday, June 10, 2015 at 8:00AM

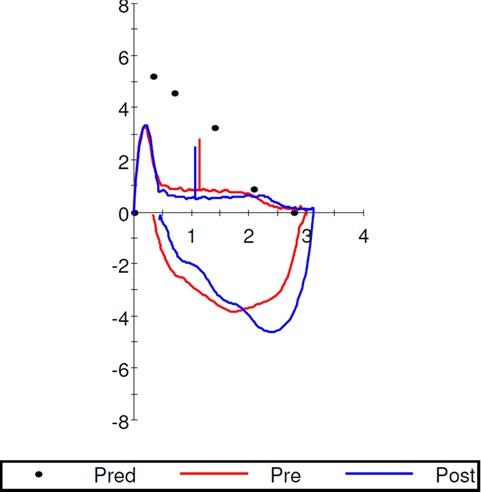

Figure 1. Flow-volume loop showing flattening of expiratory loop suggesting variable intra-thoracic obstruction.

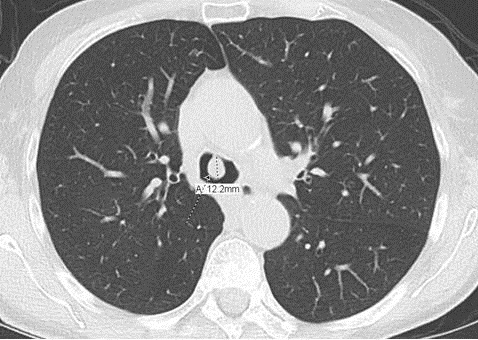

Figure 2. CT of the chest showing pedunculated tracheal lesion at the level of main carina.

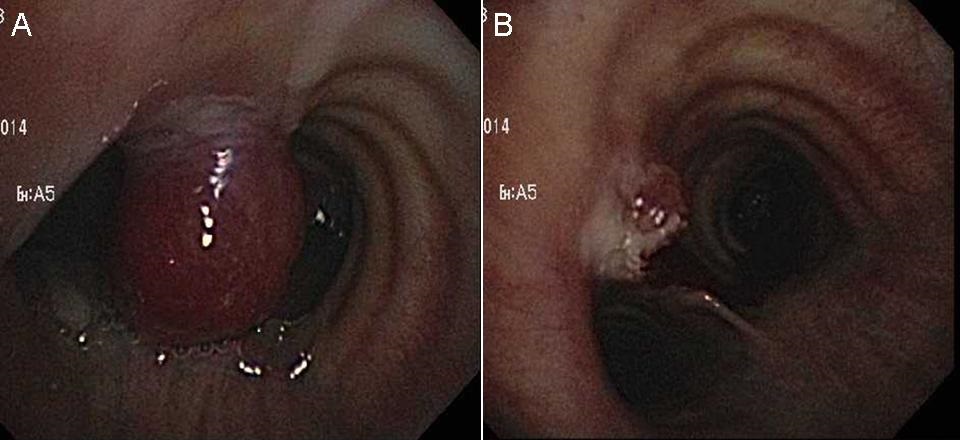

Figure 3. Bronchoscopic view of endobronchial tumor before (Panel A) and after removal (Panel B).

A 74-year-old woman with history of 30 pack-year smoking, allergic rhinitis and asthma presented to pulmonary clinic with cough and dyspnea on exertion. She was placed on inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-agonist. Pulmonary function test showed moderate obstructive ventilator defect and flow volume loop suggested variable intra-thoracic obstruction (Figure 1). In the meantime, she was hospitalized with complaint of dyspnea and possible COPD exacerbation. Het CT chest revealed an endobronchial 12 mm pedunculated lesion at anterior aspect of main carina (Figure 2). She underwent flexible bronchoscopy and lesion was removed using electro-surgical snare and cryoprobe (Figure 3). Her symptoms improved post-procedure. Pathologic examination of lesion revealed a carcinoid tumor.

Endobronchial tumors are masses confined within the bronchus, and may be associated with atelectasis or pneumonia of the distal parenchyma. These tracheobronchial tumors are classified as malignant or benign. Malignant tumors arising from surface epithelium include squamous cell carcinoma and neuro-endocrine tumors; and those arising from mesenchyme include sarcoma and malignant lymphoma. On the other hand, benign tumors arising from surface epithelium include squamous cell papilloma and mucus gland adenoma; and those arising from mesenchyme include hamartoma, lipoma, fibroma, leiomyoma, and neurogenic tumor. Hamartomas may present as a fatty mass, nodules with calcification, or as soft-tissue-density nodules on CT scans. The lipomas manifested as fat density on CT scans. The other benign tumors were low-attenuating, soft-tissue-density masses without characteristic findings on CT scans.

Tauseef Afaq Siddiqi, MD; Muhammad Alzoubaidi, MD; James Knepler, MD and Kenneth Knox, MD

Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

Reference

-

Ko JM, Jung JI, Park SH, Lee KY, Chung MH, Ahn MI, Kim KJ, Choi YW, Hahn ST. Benign tumors of the tracheobronchial tree: CT-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(5):1304-13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Reference as: Siddiqi TA, lzoubaidi M, Knepler J, Knox KS. Medical image of the week: carcinoid at the carina. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2015;10(6):341-2. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc052-15 PDF