Medical Image of the Week: Renal Cell Carcinoma Metastasis

Wednesday, September 21, 2016 at 8:00AM

Wednesday, September 21, 2016 at 8:00AM

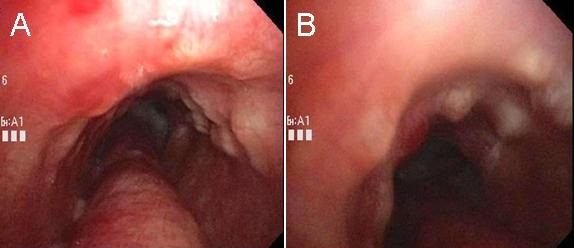

Figure 1. Panel A: Axial CT image noncontrast showing small pulmonary nodules concerning for metastasis. Panel B: Axial CT image depicting 15 cm mass, originating from the right acetabulum and adjacent iliac bone. Panel C: Coronal CT image showing prominent left renal cyst measuring almost 40 mm. Panel D: Coronal CT image displaying femoral head intact but surrounded by abnormal soft tissue, concerning for neoplasm. There is bony destruction and lytic process in the anterior and posterior pillars of the right acetabulum.

A 65-year-old man was complaining of progressive weakness and right knee pain with limping since November 2014 was admitted recently to a local hospital and treated for chronic kidney disease related anemia, Klebsiella urinary tract infection and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus wound infections. He was discharged to rehab, but continued to have progressive weakness, pain and limping. He was sent to our hospital for further evaluation and imaging.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis non contrast, due to decreased glomerular filtration rate, revealed a 15 cm mass originating from the right acetabulum and adjacent iliac bone with bony destruction and lytic processes (Figure 1). The femoral head is also surrounded by abnormal soft tissue (Figure 1D). There were also small pulmonary nodules (Figure 1A), small lymph nodes in the transverse mesocolon and retroperitoneum, and an enlarged left adrenal gland concerning for other metastasis.

CT guided biopsy of the lesion revealed a neoplastic process composed of atypical cells with centrally placed nuclei, abundant clear cytoplasm arranged in a vascular network. Immunohistochemical stains demonstrated positivity for the following: vimentin, low molecular weight keratin, CD10, RCCA, and PAX-8. These findings are consistent with metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

A total body bone scan with Tc-99m methylene diphosphonate, performed to locate other osseous metastasis, was negative for distant metastasis other than the large destructive lesion destroying the right ileum previously noted on CT.

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a cortical tumor with malignant cells originating from the epithelial lining of the proximal tubules. Renal cancer is amongst the 10 most common cancers in both men and women, with RCC accounting for about 80% of the total incidence and mortality (1). RCC has been referred to as “the internist’s tumor” as it can cause systemic symptoms unrelated to the renal cancer. The classic triad of RCC (flank pain, hematuria, and a palpable abdominal renal mass) occurs in at most 9 percent of patients (1). Most cases of RCC are diagnosed incidentally on radiographic investigation done for other reasons. Unfortunately, many patients are asymptomatic until the disease is advanced. At presentation, approximately 25% of individuals either have distant metastases or advanced local disease (2). Biopsy is not usually required to diagnose RCC. Contrast-enhanced CT can be used to diagnosis and stage RCC.

Stage IV disease has a median survival of about 12 months with systemic cytokine therapy and 28 months with targeted therapies, based on analyses from the International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) (1,3).

Erin Yen MS1, Benjamin Rayikanti MD2, Yunuen Valenzuela MD3, Jennifer Segar MD3

1 Midwestern University Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine, Phoenix

2 Tucson Hospitals Medical Education Program

3 Department of Internal Medicine, Banner University Medical Center Tucson

Tucson AZ USA

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2016. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2016/ (accessed 9/14/16).

- DeKernion JB. Real numbers. In: Campbell's Urology, Walsh PC, Gittes RF, Perlmutter AD (Eds), WB Saunders, Philadelphia 1986. p.1294.

- Heng DY, Choueiri TK, Rini BI, et al. Outcomes of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma that do not meet eligibility criteria for clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2014 Jan;25(1):149-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Yen E, Rayikanti B, Valenzuela Y, Segar J. Medical image of the week: renal cell carcinoma metastasis. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016;13(3):135-6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc068-16 PDF