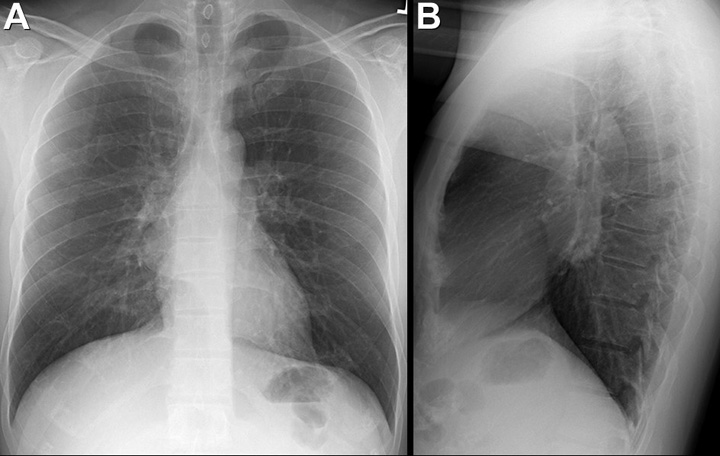

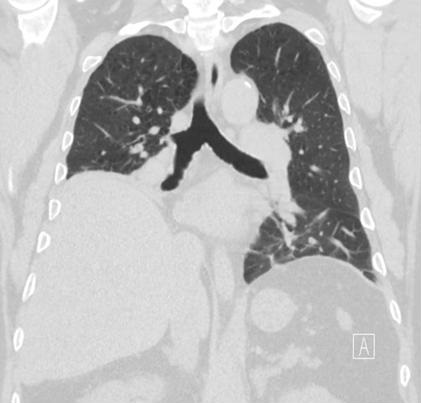

Figure 1. Image from thoracic CT scan shows persistent elevation of the right hemi diaphragm, complete right lower lobe and partial middle lobe atelectasis with patent airways on chest computed tomography.

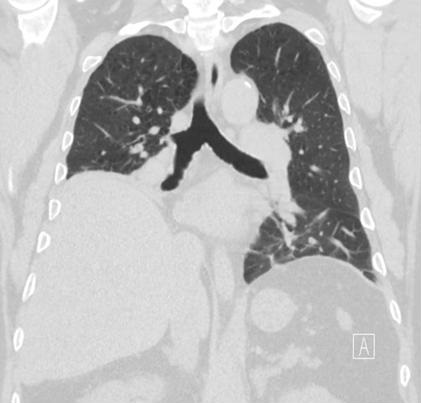

Figure 2. Diaphragm fluoroscopy demonstrating the paradoxical upward movement of the right hemi diaphragm during inspiration confirming right hemi diaphragmatic paralysis.

A 66-year-old man with a history of hypertension, morbid obesity, emphysema, type 2 diabetes complicated by extensive peripheral neuropathy presented for evaluation of persistent fatigue, shortness of breath and increased oxygen requirements.

Approximately 18 months prior to presentation the patient required intubation for septic shock with multifocal pneumonia and right lower lobe collapse. The patient left the hospital after 10 days on 4 liters of oxygen and had been oxygen dependent since then with no improvement despite aggressive pulmonary rehabilitation. A pulmonary function test (PFT) demonstrated a moderate, restrictive ventilatory defect with low diffusion capacity; while his thoracic computed tomography showed persistent elevation of the right hemi-diaphragm with right lower lobe and partial middle lobe atelectasis (Figure 1). No evidence of endobronchial lesions, mediastinal or cervical masses, or enlarged lymph nodes seen.

The patient underwent a fluoroscopic sniff test that confirmed paralysis of the right hemi-diaphragm (Figure 2) (1). Phrenic nerve palsy has been associated with cardiac surgery due to both cooling and stretching mechanisms, cervical and thoracic compression of the phrenic nerve, trauma and iatrogenic injury, Herpes zoster, poliomyelitis, neurologic amyotrophic, brachial plexopathy have been associated with unilateral and bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis (2). In our patient, extensive history, physical exam, neurologic evaluation, laboratory tests and imaging failed to reveal a provoking insult to the right phrenic nerve. Therefore, diabetes related phrenic nerve palsy was entertained as a working diagnosis due to the patient’s extensive history of diabetes related neuropathy. The patient was started on noninvasive positive pressure ventilation with a BiPAP machine and showed remarkable symptomatic improvement at bedtime, but his functional status has been significantly limited during the day. He is currently being evaluated for possible diaphragmatic plication surgery.

Surgical plication of the paralyzed hemi diaphragm has shown very good results in appropriately selected patients (3). This included improvement in lung function, exercise endurance, and dyspnea post surgery.

Richard Young, MD*, Ateeli Huthayfa, MBBS**, Afishin Sam, MD**.

*Department of Internal Medicine. **Department of Pulmonology and Critical Care

Banner University Medical Center, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona

References

- Nason LK, Walker CM, McNeeley MF, Burivong W, Fligner CL, Godwin JD. Imaging of the diaphragm: anatomy and function. Radiographics. 2012 Mar-Apr;32(2):E51-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson GJ. Diaphragmatic paresis: pathophysiology, clinical features, and investigation. Thorax. 1989 Nov;44(11):960-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hüttl TP, Wichmann MW, Reichart B, Geiger TK, Schildberg FW, Meyer G. Laparoscopic diaphragmatic plication: long-term results of a novel surgical technique for postoperative phrenic nerve palsy. Surg Endosc. 2004 Mar;18(3):547-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Young R, Huthayfa A, Sam A. Medical image of the week: a positive sniff test. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;14(5):199-200. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc050-17 PDF

Thursday, May 4, 2017 at 10:02AM

Thursday, May 4, 2017 at 10:02AM