The “Hidden Attraction” of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Diagnosing Pulmonary Embolism

Friday, May 12, 2017 at 8:00AM

Friday, May 12, 2017 at 8:00AM Ahmed A. Harhash MD1

James Cassuto MD PhD2

Ryan J. Avery MD3

Phillip H. Kuo MD PhD3

1Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, and the 3Department of Radiology University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona USA

2Department of Radiology, Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, Florida USA

Abstract

While various modalities exist for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE), CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is the most widely used and can establish the diagnosis quickly and reliably. We report a patient who presented with syncope who developed pulseless electrical activity (PEA) arrest in the emergency department. Given the presence of acute renal injury, CTA was felt to be contraindicated. A ventilation-perfusion lung (VQ) scan demonstrated low probability for PE; however, echocardiography revealed evidence for right heart strain. Subsequent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) unexpectedly revealed a saddle PE. This case highlights the potential role for MR for the diagnosis of PE when high clinical suspicion is discordant with results of conventional imaging.

Introduction

High-risk acute pulmonary embolism (PE) - generally defined as patients presenting with shock or hypotension- is associated with up to 22% 30-day mortality (1). The role of imaging for diagnosing PE is critical, with CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) the most widely used and generally accepted as the test of choice. CTPA offers high sensitivity and specificity for PE, short acquisition time, and the ability to diagnose alternative diagnoses in patients presenting with symptoms suggesting acute PE but with negative CTPA results. In the setting of stable chronic renal insufficiency (GFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73m2) the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy from intravenous iodinated contrast media is low, and administration of iodinated intravenous contrast in this setting considered safe for most patients (2). However, few data regarding the safety of CTPA in the setting of worsening acute kidney injury are available. In these circumstances, an understanding of alternative imaging modalities for the assessment of suspected acute PE is critical.

Case Presentation

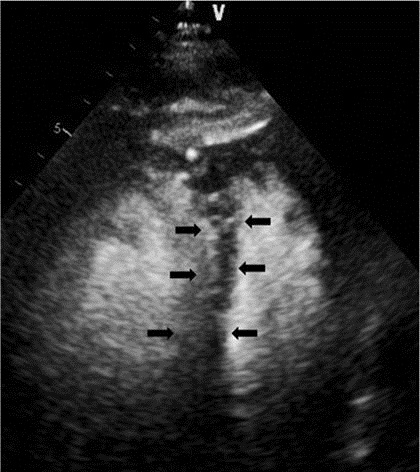

A 61-year-old man with no past medical history presented unresponsive to the emergency department after collapsing while shopping. The patient was minimally arousable during initial assessment and reported sudden onset of shortness of breath prior to syncope. In the emergency room, the patient developed pulseless electrical activity- cardiac arrest. Return of spontaneous circulation was achieved after 2-cycles of CPR and endotracheal intubation. The patient then developed ventricular fibrillation with return of spontaneous circulation following defibrillation. The ECG demonstrated supraventricular arrhythmia with right bundle branch block. Emergent cardiac catheterization was performed for possible acute coronary syndrome but revealed no obstructive lesions. CT pulmonary angiography was then considered to evaluate for PE, however alternative examinations were pursued secondary to acute kidney injury (creatinine 2.3 mg/dL vs. baseline 1.1 mg/dL). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed right ventricular enlargement and hypokinesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Apical four chamber view (transthoracic echocardiogram after intravenous administration of DEFINITY® perflutren lipid microsphere) demonstrated septal flattening consistent with right ventricular pressure/volume overload (black arrows).

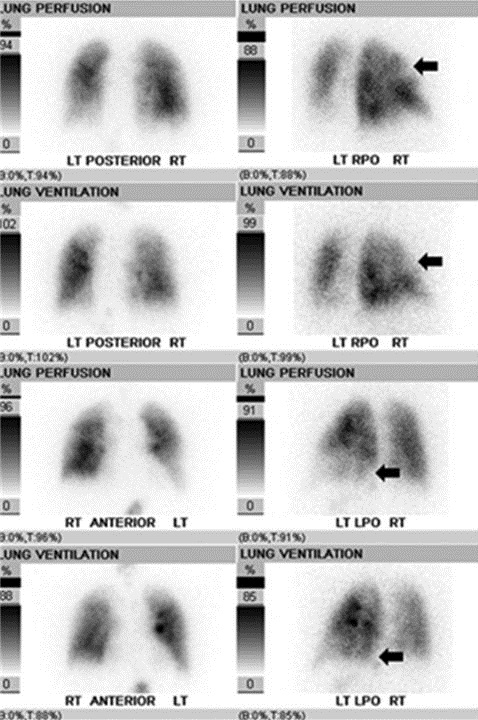

Immediate anticoagulation with intravenous heparin infusion was started as clinical suspicion for PE was high, particularly given the presence of right heart strain. The patient regained hemodynamic stability and was extubated by hospital day three. To assess for the presence of PE, a VQ scan was performed, which showed low probability for PE (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Nuclear ventilation-perfusion scan was performed first with 50 millicuries of technetium-99m diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid aerosol administered via inhalation with multi-view planar imaging of the lungs, followed by intravenous administration of 6 millicuries of technetium-99m macroaggregated albumin with repeat multi-view planar imaging. Matched ventilation-perfusion defects are seen involving the anterior and apical right upper lobe and basal posterior left lower lobe (black arrows), no segmental mismatched perfusion defects were detected. The final impression was low probability for acute pulmonary embolism.

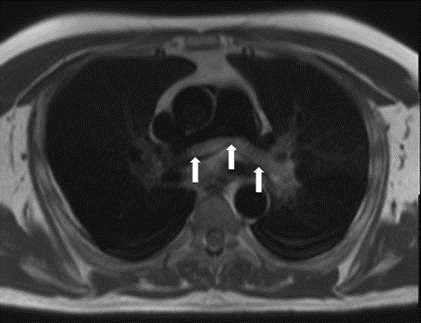

As the RV dysfunction remained unexplained, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) was performed to evaluate right ventricular function and revealed no intrinsic RV disease, but did reveal a central, “saddle” PE (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Axial black blood cardiac MRI sequence (free breathing HASTE, TR 700 ms, TE 46 ms, slice thickness 8mm, slice gap 2mm) was performed prior to intravenous contrast injection and revealed a non-obstructive saddle embolus at the bifurcation of the pulmonary trunk (white arrows).

Discussion

The incidence of symptomatic venous thromboembolism in adults is 1-2:1000, with one-third of patients presenting with PE. Early diagnosis is the cornerstone for improving outcomes due to acute PE - mortality decreases from 25% to 2-8% with prompt management (3). As the array of imaging modalities expands, the role and value of radiologists as consultants for guiding clinicians for the evaluation of PE also increases, particularly for complicated patients. This case highlights both a pitfall in the use of VQ scanning and a role for MR for evaluating PE. For PE patients with non-occlusive thrombus and balanced oligemia, as in the patient presented, lungs may show no mismatched defects. This situation may lead to a falsely low probability VQ scan result as the test relies upon the relative perfusion (or lack thereof) of lung segments compared to others. Prior to the VQ scan, the patient had been anticoagulated for three days with marked clinical improvement. Accordingly, the VQ scan might have been high probability had it been performed prior to anticoagulation. As reported in the PIOPED I study, which integrated both clinical and imaging findings, a low probability VQ scan in the context of high clinical suspicion was associated with 21% probability of PE at catheter pulmonary angiography (4).

This case demonstrates that CMR can incidentally diagnose central PE, although CMR protocols are optimized for cardiac evaluation and not for PE detection, and therefore should never be used in place of dedicated exams for PE.

Magnetic resonance pulmonary angiography offers several advantages for PE evaluation compared with CTPA, including utilization of non-ionizing radiation and not requiring the use of iodinated contrast agents. However, historically, pulmonary MR imaging has been hampered by long acquisition times, limited spatial resolution, and inadequate volumes of coverage compared with CTPA (5). The largest efficacy study of the use of MR pulmonary angiography for the diagnosis of acute PE was the PIOPED III study, in which 371 patients underwent contrast-enhanced pulmonary MRA for the assessment of suspected PE. Pulmonary MR examinations were compared with references standards to establish or exclude the diagnosis of PE. In the PIOPED III study, pulmonary MRA was found to be technically inadequate in 25% of patients, typically the result of poor pulmonary arterial opacification or motion artifacts, with the sensitivity of pulmonary MRA only 57% when including the patients with technically inadequate examinations (6). While specificity for PE diagnosis was high (99%), the sensitivity of pulmonary MRA only rose to 78% when technically limited examinations were excluded. The PIOPED III study has frequently been cited as a cautionary note regarding the use of pulmonary MR to diagnose PE, but it should be noted that this study only employed one technique for the evaluation of possible PE- pulmonary MRA- and the technical aspects of the MR acquisition are now over a decade old (5). Recent improvements in scanner technology, including shorter echo times, time-resolved imaging, improved receiver coils and gradients, more optimized bolus injection techniques, and the implementation of parallel imaging, have reduced acquisition times and decreased artifacts, allowing for more robust MR pulmonary imaging (5). Furthermore, a multiparametric approach to venous thromboembolism imaging using MR, including unenhanced imaging employing balanced steady state free precession sequences combined with enhanced imaging, first using time-resolved contrast-enhanced perfusion imaging, followed by pulmonary MRA using a rapid 3D spoiled gradient echo sequence (typically several vascular phase acquisitions are obtained to optimize pulmonary arterial enhancement), and completed with an additional post-contrast T1-weighted spoiled gradient recalled acquisition, provide complete pulmonary vascular assessment and offer multiple methods for PE detection should one particular sequence be suboptimal (5). A more recent single center study of 190 patients undergoing magnetic resonance pulmonary angiography using a multiparametric approach as the primary study to evaluate for PE showed the negative predictive value of the test to be 97% at 3-months and 96% at 12-months follow-up, similar to CTPA (7). Furthermore, while magnetic resonance pulmonary angiography may show somewhat reduced sensitivity for the detection of distal segmental and sub-segmental PE compared with CTPA, the clinical relevance of such small emboli remains in doubt and many patients with such small emboli may not require anticoagulation.

Conclusion

We report the somewhat unusual finding of central, “saddle” PE diagnosed using cardiac MR in a patient with clinical suspicion for PE but a low probability VQ scan. Our study highlights the important and growing role of MR for the diagnosis of acute PE and serves as a reminder to evaluate all structures within the field of view, not just the heart, when interpreting CMR examinations. Even with the amazing advances in imaging, no imaging modality is perfect and clinical acumen should never be replaced or discounted, especially for a diagnosis as critical as PE.

References

- Becattini C, Agnelli G, Lankeit M, et al. Acute pulmonary embolism: mortality prediction by the 2014 European Society of Cardiology risk stratification model. Eur Respir J. 2016 Sep;48(3):780-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport MS, Khalatbari S, Cohan RH, Dillman JR, Myles JD, Ellis JH. Contrast material-induced nephrotoxicity and intravenous low-osmolality iodinated contrast material: risk strati cation by using estimated glomerular ltration rate. Radiology. 2013;268(3):719-728. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavorini F, Di Bello V, De Rimini ML, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary embolism: a multidisciplinary approach. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2013 Dec 19;8(1):75. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worsley DF, Alavi A. Comprehensive analysis of the results of the PIOPED Study. Prospective Investigation of Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis Study. J Nucl Med. 1995 Dec;36(12):2380-7. [PubMed]

- Schiebler ML, Nagle SK, François CJ. Effectiveness of MR angiography for the primary diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes at 3 months and 1 year. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013 Oct;38(4):914-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein PD, Chenevert TL, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, Gottschalk A, Hales CA, et al. Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography for pulmonary embolism: amulticenter prospective study (PIOPED III). Ann Intern Med 2010;152(7):434-43, . [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiebler ML, Nagle SK, François CJ. Effectiveness of MR angiography for the primary diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes at 3 months and 1 year. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;38(4):914-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Harhash AA, Cassuto J, Avery RJ, Kuo PH. The “hidden attraction” of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosing pulmonary embolism. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;14(5):230-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc057-17 PDF