Medical Image of the Week: Headcheese Sign

Wednesday, April 4, 2018 at 8:00AM

Wednesday, April 4, 2018 at 8:00AM

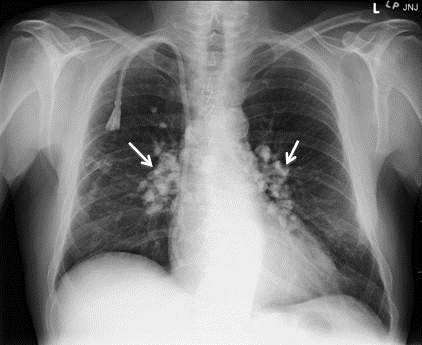

Figure 1. Representative image from thoracic CT scan showing ground glass opacities, most prominent in the lower lung fields bilaterally with air trapping.

A 95-year-old woman with a past medical history of breast cancer and mastectomy presented with fevers, cough productive of sputum and progressive dyspnea for 2 weeks. She denies any recent travel or sick contacts but has bird at home since last 10 years. She was afebrile but tachypneic with respiratory rate of 25 and sPO2 of 86% on room air. Her initial chest examination reveals coarse rhonchi in both lungs. Labs were significant for a sodium of 118 mEq/L, leukocytosis to 18,000 cells/mcL without peripheral eosinophilia. Arterial blood gas showed pO2 of 55 mm Hg, pCO2 of 48 mm Hg and pH of 7.44. An initial chest X-ray was positive for extensive bilateral pulmonary infiltrates predominantly in the mid and lower lungs with areas of airspace consolidation. Her urine Streptococcus pneumoniae antigen was negative as well as rapid influenza and a respiratory syncytial virus panel. The high resolution thoracic CT showed scattered ground glass opacities, most prominent in the lower lung fields bilaterally (Figure 1). Small more focal consolidative opacities are seen in the right upper lobe. As there was a juxtaposition of low, normal and high-attenuated area of CT scan, characteristic of the headcheese sign.

The head cheese sign is indicative of a mixed obstructive and infiltrative process (1). The low attenuated regions reflect air trapping suggestive of obstructive small airway disease and vasoconstriction due to hypoxia (2). Expiration CT may be needed to enhance low attenuation areas. This airway pathology leads to mosaic attenuation on HRCT. The most common cause of this radiological sign is hypersensitivity pneumonitis (3). As our patient had a long exposure to bird, it was probably the cause of her lung pathology. Other causes of the headcheese sign such as sarcoidosis, bronchiolitis, mycoplasma pneumonia or desquamative interstitial pneumonitis should be considered.

Learning Points:

- Headcheese is a radiological sign suggestive of hypersensitivity pneumonitis as most common cause.

- Occupation or any animal exposure history will be most useful in this scenario.

- The clinician should rule out other causes such as an infectious etiology or sarcoidosis.

Ajay Adial MD, Danial Arshed MD, Lourdes Sanso MD, and Asma Iftikhar MD

Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine

New York-Presbyterian/Queens

New York, NY USA

References

- Webb WR. Thin-section CT of the secondary pulmonary lobule: anatomy and the image--the 2004 Fleischner lecture. Radiology. 2006 May;239(2):322-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschmann JV, Pipavath SN, Godwin JD. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a historical, clinical, and radiologic review. Radiographics. 2009 Nov;29(7):1921-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel RA, Sellami D, Gotway MB, Golden JA, Webb WR. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: patterns on high-resolution CT. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000 Nov-Dec;24(6):965-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Adial A, Arshed D, Sanso L, Iftikhar A. Medical image of the week: headcheese sign. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;16(4):192-3. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc040-18 PDF