Salma Batool-Anwar, MD, MPH1

Olabimpe Omobomi, MD, MPH1

Stuart F. Quan, MD1,2

1Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Division of Sleep Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, 2Arizona Respiratory Center, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, AZ.

Abstract

Background: To examine the effect of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) on Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as measured by the Quality of Well Being Self-Administered questionnaire (QWB-SA).

Methods: Participants from The Apnea Positive Pressure Long-term Efficacy Study (APPLES); a 6-month multicenter randomized, double-blinded intention to treat study, were included in this analysis. The participants with an apnea-hypopnea index >10 events/hour initially randomized to CPAP or Sham group were asked to complete QWB-SA at baseline, 2, 4, and 6-month visits.

Results: There were no group differences among either the CPAP or Sham groups. Mean age was 52±12 (SD] years, AHI 40±25 events/hr, BMI 32±7.1 kg/m2, and Epworth Sleepiness Score (ESS) 10±4 of 24 points. QWB-SA scores were available at baseline, and 2, 4 & 6 months after treatment in CPAP (n 558) and Sham CPAP (n 547) groups. There were no significant differences in QWB scores among mild, moderate or severe OSA participants at baseline. Modest improvement in QWB scores was noted at 2, 4 and 6- months among both Sham and CPAP groups (P <0.05). However, no differences were observed between Sham CPAP and CPAP at any time point. Comparison of the QWB-SA data from the current study with published data in populations with chronic illnesses demonstrated that the impact of OSA is no different than the effect of AIDS and arthritis.

Conclusion: Although the QoL measured by the QWB-SA was impaired in OSA it did not have direct proportionality to OSA severity.

Introduction

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is characterized by recurrent episodes of upper airway narrowing and oxygen desaturation with resultant frequent nighttime awakenings and daytime sleepiness (1). A strong association between OSA and obesity has been described (2), and with the global epidemic of obesity (3), the prevalence of OSA is anticipated to increase. Recent studies have reported an increase in prevalence from 22 to 37% among men, and 17 to 50% among women (4).

Health related quality of life (HRQoL) relates to a World Health Organization definition of health comprised of physical, mental, spiritual and social wellbeing (5). A variety of questionnaires are used in epidemiologic studies to assess quality of life (QoL). Studies demonstrate that QoL is worse in persons with OSA (6). Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the gold standard for treating OSA and improves daytime sleepiness among adherent patients (7). However, studies examining the effect of CPAP on quality of life have not found consistent results (8,9). These discrepancies are attributed to the fact that there are two types of questionnaires which are used to assess QoL; generic or disease specific. Utilizing data from the Apnea Positive Pressure long term Efficacy Study (APPLES), a randomized controlled trial of CPAP vs Sham CPAP, we analyzed whether CPAP improved HRQoL using the self-administered version of the Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB-SA), a well-validated generic HRQoL instrument, that has not been validated in OSA.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Protocol. APPLES was a 6-month multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, 2-arm, sham-controlled, intention-to-treat study of CPAP efficacy on three domains of neurocognitive function in OSA. A detailed description of the protocol has previously been published (10). Briefly, the participants were recruited either through local advertisement or from those attending sleep clinics for evaluation of possible OSA. Symptoms indicative of OSA were used to screen potential participants. The initial clinical evaluation included administering informed consent and screening questionnaires as well as history and physical examination and medical assessment by a study physician. Participants subsequently returned 2-4 weeks later for a baseline 24-h sleep laboratory visit, during which polysomnography (PSG) was performed to confirm the diagnosis followed by a day of neurocognitive, mood, sleepiness, and QoL testing. Inclusion criteria have been published previously and included age ≥ 18 years and a clinical diagnosis of OSA, as defined by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) criteria. Only participants with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 10 by PSG were randomized to CPAP or sham CPAP and continued in the APPLES study. Exclusion criteria included previous treatment for OSA with CPAP or surgery, oxygen saturation on the baseline PSG <75% for >10% of the recording time, history of a motor vehicle accident related to sleepiness within the past 12 months, presence of several chronic medical conditions, use of various medications known to affect sleep or neurocognitive function, and other health and social factors that may impact standardized testing procedures (e.g., shift work). After randomization, participants underwent a CPAP or sham CPAP titration and were followed for 6 months on their assigned intervention. Subsequent study visits occurred at 2, 4 and 6 months after the titration PSG. The APPLES study was approved by an institutional review board for human studies at each clinical site; informed consent was obtained from all participants at the time of enrollment as previously described.

Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB). The QWB is a comprehensive measure of HRQoL. It has been extensively validated and can be used to calculate quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) (11). Because of its complexity, a self-administered version, the QWB-SA was developed (12). The questionnaire is sensitive to changes at the higher levels of functioning and can also produce estimates of QALY for cost-effectiveness analyses. The QWB-SA includes 5 sections. The first assesses the presence/absence of 19 chronic symptoms or problems (e.g., blindness, speech problems). These chronic symptoms are followed by 25 acute (or more transient) physical symptoms (e.g. headache, coughing, pain), and 14 mental health symptoms and behaviors (e.g., sadness, anxiety, irritation). The remaining sections of the QWB-SA include assessments of mobility (including use of transportation), physical activity (e.g., walking and bending over) and social activity including completion of role expectations (e.g., work, school, or home). Scores from each subscale are coupled with population derived weights to yield one composite score ranging from 0.09 (lowest possible health state to 1 for perfect health, with zero meaning death.

The QWB-SA was administered at the baseline study visit and at each subsequent study visit. At each visit, we collected three scores (QWB1, QWB2, and QWB3) corresponding to the day of the survey and the immediate 2 previous days. These scores included combinations of questions from the 5 sections as follows:

- Part I: Acute and chronic symptoms

- Part II: Self Care

- Part III: Mobility

- Part IV: Physical activity

- Part V: Social activity

To calculate the QWB-SA the scores for each section were computed and combined according to guidelines provided by the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Health Services Research Center to yield the QWB score for each day. From the daily scores, the QWB Average Score was derived as the mean of QWB1+QWB2+QWB3. We used the QWB Average Score in subsequent analyses.

Polysomnography (PSG). The PSG montage included monitoring of the electroencephalogram (EEG, C3-A2 or C4-A1, O2-A1 or O1-A2), electrooculogram (EOG, ROC-A1, LOC-A2), chin and anterior tibialis electromyograms (EMG), heart rate by 2-lead electrocardiogram, snoring intensity (anterior neck microphone), nasal pressure (nasal cannula), nasal/oral thermistor, thoracic and abdominal movement (inductance plethysmography bands), and oxygen saturation (pulse oximetry). All PSG records were electronically transmitted to a centralized data coordinating and PSG reading center. Sleep and wakefulness were scored using Rechtschaffen and Kales criteria (13). Apneas and hypopneas were scored using the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force diagnostic criteria (14). Briefly, an apnea was defined by a clear decrease (> 90%) from baseline in the amplitude of the nasal pressure or thermistor signal lasting ≥ 10 sec. Hypopneas were identified if there was a clear decrease (> 50% but ≤ 90%) from baseline in the amplitude of the nasal pressure or thermistor signal, or if there was a clear amplitude reduction of the nasal pressure signal ≥ 10 sec that did not reach the above criterion, but was associated with either an oxygen desaturation > 3% or an arousal. Obstructive events were scored if there was a persistence of chest or abdominal respiratory effort. Central events were noted if no displacement occurred on either the chest or abdominal channels. The AHI was computed as the number of apneas and hypopneas divided by the total sleep time. Sleep apnea was classified as mild (AHI 10.0 to 15.0 events per hour), moderate (AHI 15.1 to 30.0 events per hour), and severe (AHI more than 30 events per hour) (14).

CPAP Adherence. Nightly use of CPAP was downloaded from the device and was assessed at 2, 4, 6-month intervals. The participants were considered adherent if CPAP use was ≥ 4 hours per night for >70% of nights.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). The ESS is a validated self-completion tool that asks subjects to rate the likelihood of falling asleep in eight common situations using four ordinal categories ranging from 0 (no chance) to 3 (high chance) (15). Scores range from 0 to 24 with a score >10 suggesting EDS (15).

Calgary Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index (SAQLI). The SAQLI was developed as a sleep apnea specific quality of life instrument (16). It is a 35-item instrument that captures the adverse impact of sleep apnea on 4 domains: daily functioning, social interactions, emotional functioning and symptoms. Items are scored on a 7- point scale with “all of the time” and “not at all” being the most extreme responses. Item and domain scores are averaged to yield a composite total score between 1 and 7. Higher scores represent a better quality of life.

Statistical Analysis. Simple linear and multiple regression models were used to estimate the degree to which variables correlated with QWB scores. We examined the association between the QWB-SA and the following variables: OSA severity as measured by the AHI, sleepiness as assessed by ESS, age, and baseline body mass index (BMI, kg/m2). Severity of OSA in this study was defined according to the AHI as follows: Mild (10-<15 /h), Moderate (15-<30 /h), Severe (>30 /h). Changes in QWB-SA over the duration of the study were analyzed using a mixed model repeated measures analysis of variance with participants stratified by their randomization group (CPAP or Sham CPAP). Analyses were performed using STATA (version 11, StataCop TX USA) and IBM SPSS v24 (Armonk, NY). Finally, we compared the sample means to the normative means using GraphPad Prism8.

Results

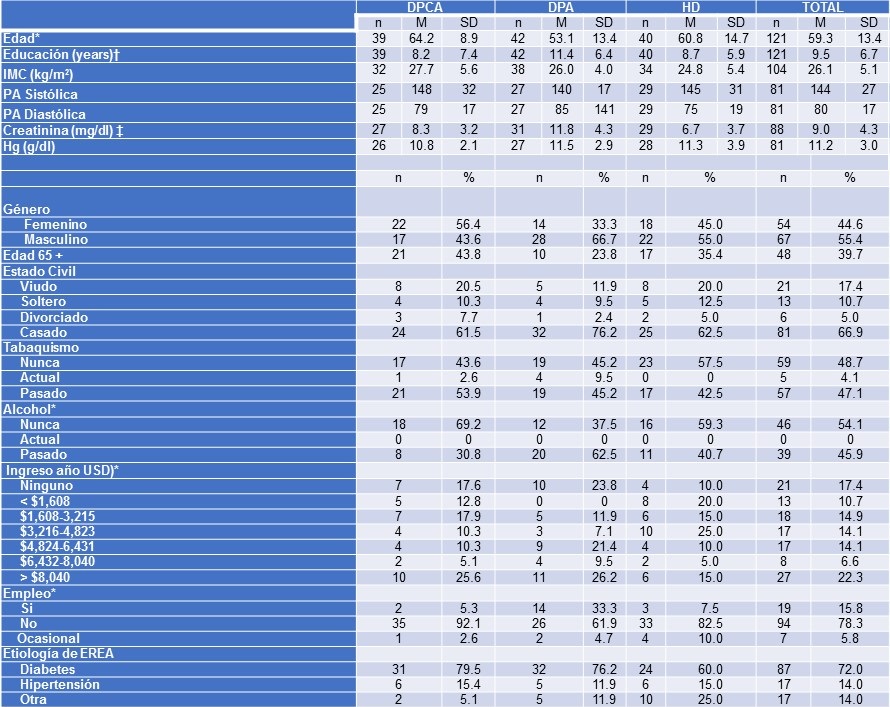

Initially, 558 participants were randomized to CPAP and 547 to Sham CPAP. As shown in Table 1, age, gender, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), AHI, and ESS were similar between the CPAP and Sham CPAP groups.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

SD: Standard Deviation, BMI: Body Mass Index, AHI: Apnea Hypopnea Index, ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale, SAQLI: Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index, QWB: Quality of wellbeing

Men comprised of 50% of the study population and the population was generally obese (CPAP: BMI 32.4 ± 7.3; Sham: BMI 32.1 ± 6.9 kg/m2). The participants overall had at least 15 years of education, and over 50% of the participants were either married or living with someone. The sample population did not report severe excessive daytime sleepiness with the reported ESS approximately 10 in both the CPAP and SHAM groups. Similarly, there were no significant differences in SAQLI score, total sleep time or arousal index among the two treatment groups.

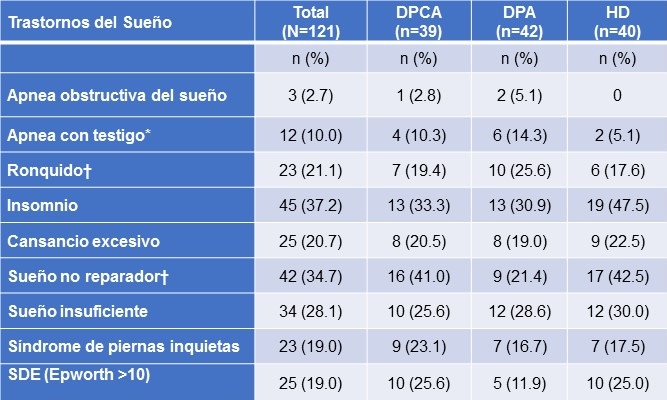

Scores for the QWB-SA were available at baseline and 2, 4 and 6 months after treatment in both groups. As shown in Table 2, there were no significant differences in QWB-SA at baseline between both groups.

Table 2. Mixed model analysis for the effect of time on QWB average score among CPAP and SHAM groups (N=1104).

*QWB-SA scores improved in both groups over the 6 months of follow-up, p<0.05.

In addition, scores among mild, moderate or severe OSA participants at baseline also were not different (data not shown). Modest improvement in QWB scores was noted at 2, 4 and 6- month among both Sham and CPAP groups (P<0.05). However, no differences were observed between Sham CPAP and CPAP at any time point. Furthermore, multiple regression analyses stratified by OSA severity, gender, and mean adherence to CPAP or Sham CPAP suggested significant improvement in QWB scores only among women with severe OSA in the CPAP group (data not shown, P <0.05).

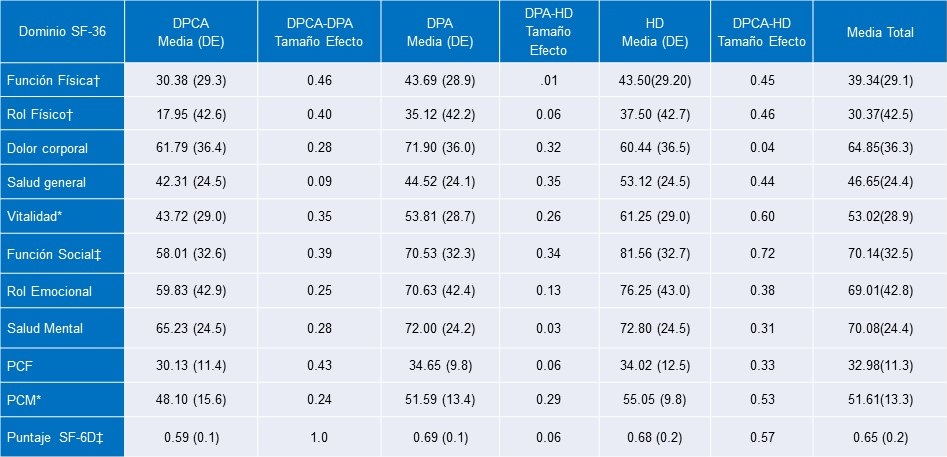

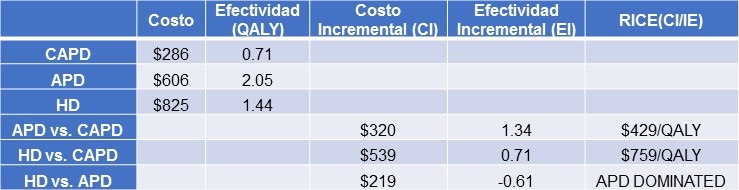

Table 3 shows comparisons of the QWB-SA from the current study with published data in populations with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD), arthritis and prostate cancer (17-20).

Table 3. Comparison of sample mean to normative means.

QWB: Quality of Wellbeing, CF: Cystic Fibrosis, OSA: obstructive Sleep Apnea, AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency syndrome, COPD: Chronic Obstructive pulmonary Disease.

The impact of OSA is not different than the effect of AIDS and arthritis and only slightly less than with COPD and prostate cancer.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the effect of CPAP therapy on QoL using the QWB-SA questionnaire. We found that the cross-sectional mean QWB-SA scores were comparable to the scores found in other chronic illnesses (COPD, arthritis, cystic fibrosis, prostate cancer, and AIDS) (17-20) indicating that quality of life is adversely affected by sleep apnea similar to these chronic conditions. Although the QWB-SA modestly declined over a treatment duration of 6 months, the instrument was unable to distinguish any differences between CPAP and sham CPAP. Moreover, these findings remained after stratifying based on PAP adherence and OSA severity.

Assessment of quality of life (QoL) is an integral part of OSA management and various scales are being used by researchers. Studies using these instruments generally find that QoL is impaired in persons with OSA (6). However, to our knowledge, there have not been previous studies using the QWB-SA in a population with OSA. Our findings which demonstrate that the QWB-SA is low in OSA are consistent with these prior investigations. However, in contrast to our observations, some but not all studies have noted a greater impact of OSA on QoL in those with more severe disease. For example, Baldwin et al. (21) in the Sleep Heart Health Study found that there was a higher risk of having an impact on the vitality subscale of SF-36 with greater OSA severity. In contradistinction, Fornas et al. (22) using the Nottingham Health Profile found no relationship between OSA severity and differences in QoL in a moderate size group of OSA patients. This discrepancy may relate to whether a general population as in Baldwin et al or a clinical population as in Fornas et al. was studied. Additionally, instruments used to quantify QoL may assess different domains, thus leading to different conclusions. Thus, while the QWB-SA can detect that QoL is impaired in those with OSA, it does not have the capability to distinguish subtleties related to differences in OSA severity.

At baseline, we observed that scores on the QWB-SA were comparable to those found for patients with AIDS (23) and arthritis (20) but were slightly higher than those with COPD (18), cystic fibrosis (CF) (24), and prostate cancer (19). They are notably better than chronic renal failure on hemodialysis (0.49) (25). Thus, it appears that the impact of OSA on QoL is approximately the same as several but not all other chronic conditions that are viewed by the general public as having considerably greater health consequences.

Contrary to its use in cystic fibrosis and AIDS where QWB-SA has validity as an outcome measure (18-24) we did not find that the QWB-SA was able to detect changes in QoL with the use of CPAP. This observation also is contradistinction to results from the CPAP Apnea Trial North American Program using the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ) as well as analyses of the Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Inventory (SAQLI) in the APPLES (26,27) study. In contrast to QWB-SA, both the FOSQ and SAQLI are sleep specific QoL instruments. Thus, the results of our study provide additional evidence that a generic HRQoL instrument may not be sensitive to the specific QoL domains impacted by treatment of OSA using CPAP. Other studies have concluded that changes in QoL in response to CPAP therapy may vary depending on the QoL measure used and that some measures may be more sensitive to detecting changes to QoL with CPAP therapy than others (28). A randomized control trial with a total of 1256 patients comparing various QoL tools concluded that generic QoL tools may not be sufficient at detecting important changes in QoL in OSA patients as CPAP may not improve general QoL scores but rather specific QoL domains. For instance, in that analysis, the SF-36 tool demonstrated positive changes only in physical function and energy levels with CPAP (29). In contrast, a study comparing 2 sleep specific QoL instruments to the generic 36-item short form survey (SF-36), found that the FOSQ and SAQLI provided unique information about health outcomes in treated OSA patients (30) and correlated well with the SF36 survey domains. In that study, the FOSQ was found to be more sensitive to differences in CPAP adherence than the SAQLI.

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the effect of CPAP on QoL using the QWB-SA questionnaire. A major strength of the study is that it utilized data from a large multicenter randomized controlled trial with follow up and interval documentation of CPAP adherence for up to 6 months. However, there were several limitations. First, the study population was a mixture of patients recruited from sleep clinics and the general population; this may have resulted in a differential impact on QoL. Second, overall adherence to both CPAP and sham CPAP was relatively poor although not inconsistent with the results from other studies. Finally, QoL was assessed using the average QWB-SA total scores and hence it is unclear whether there may have been improvements in specific domains over time with CPAP treatment.

In conclusion, despite the limitations, we found that QoL measured by the QWB-SA was impaired in OSA but was not found to have direct proportionality to OSA severity. Furthermore, it was not sufficiently sensitive for detecting QoL changes in OSA patients on CPAP therapy. Our data support the use of sleep apnea specific QoL questionnaires for measurement of QoL after initiation of CPAP.

Acknowledgments

The Apnea Positive Pressure Long-term Efficacy Study (APPLES) study was funded by contract 5UO1-HL-068060 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. The APPLES pilot studies were supported by grants from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Medicine Education and Research Foundation to Stanford University and by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (N44-NS-002394) to SAM Technology. In addition, APPLES investigators gratefully recognize the vital input and support of Dr. Sylvan Green, who died before the results of this trial were analyzed, but was instrumental in its design and conduct.

Administrative Core: Clete A. Kushida, MD, PhD; Deborah A. Nichols, MS; Eileen B. Leary, BA, RPSGT; Pamela R. Hyde, MA; Tyson H. Holmes, PhD; Daniel A. Bloch, PhD; William C. Dement, MD, PhD

Data Coordinating Center: Daniel A. Bloch, PhD; Tyson H. Holmes, PhD; Deborah A. Nichols, MS; Rik Jadrnicek, Microflow, Ric Miller, Microflow Usman Aijaz, MS; Aamir Farooq, PhD; Darryl Thomander, PhD; Chia-Yu Cardell, RPSGT; Emily Kees, Michael E. Sorel, MPH; Oscar Carrillo, RPSGT; Tami Crabtree, MS; Booil Jo, PhD; Ray Balise, PhD; Tracy Kuo, PhD

Clinical Coordinating Center: Clete A. Kushida, MD, PhD, William C. Dement, MD, PhD, Pamela R. Hyde, MA, Rhonda M. Wong, BA, Pete Silva, Max Hirshkowitz, PhD, Alan Gevins, DSc, Gary Kay, PhD, Linda K. McEvoy, PhD, Cynthia S. Chan, BS, Sylvan Green, MD

Clinical Centers

Stanford University: Christian Guilleminault, MD; Eileen B. Leary, BA, RPSGT; David Claman, MD; Stephen Brooks, MD; Julianne Blythe, PA-C, RPSGT; Jennifer Blair, BA; Pam Simi, Ronelle Broussard, BA; Emily Greenberg, MPH; Bethany Franklin, MS; Amirah Khouzam, MA; Sanjana Behari Black, BS, RPSGT; Viola Arias, RPSGT; Romelyn Delos Santos, BS; Tara Tanaka, PhD

University of Arizona: Stuart F. Quan, MD; James L. Goodwin, PhD; Wei Shen, MD; Phillip Eichling, MD; Rohit Budhiraja, MD; Charles Wynstra, MBA; Cathy Ward, Colleen Dunn, BS; Terry Smith, BS; Dane Holderman, Michael Robinson, BS; Osmara Molina, BS; Aaron Ostrovsky, Jesus Wences, Sean Priefert, Julia Rogers, BS; Megan Ruiter, BS; Leslie Crosby, BS, RN

St. Mary Medical Center: Richard D. Simon Jr., MD; Kevin Hurlburt, RPSGT; Michael Bernstein, MD; Timothy Davidson, MD; Jeannine Orock-Takele, RPSGT; Shelly Rubin, MA; Phillip Smith, RPSGT; Erica Roth, RPSGT; Julie Flaa, RPSGT; Jennifer Blair, BA; Jennifer Schwartz, BA; Anna Simon, BA; Amber Randall, BA

St. Luke's Hospital: James K. Walsh, PhD, Paula K. Schweitzer, PhD, Anup Katyal, MD, Rhody Eisenstein, MD, Stephen Feren, MD, Nancy Cline, Dena Robertson, RN, Sheri Compton, RN, Susan Greene, Kara Griffin, MS, Janine Hall, PhD

Brigham and Women's Hospital: Daniel J. Gottlieb, MD, MPH, David P. White, MD, Denise Clarke, BSc, RPSGT, Kevin Moore, BA, Grace Brown, BA, Paige Hardy, MS, Kerry Eudy, PhD, Lawrence Epstein, MD, Sanjay Patel, MD

Sleep HealthCenters for the use of their clinical facilities to conduct this research

Consultant Teams

Methodology Team: Daniel A. Bloch, PhD, Sylvan Green, MD, Tyson H. Holmes, PhD, Maurice M. Ohayon, MD, DSc, David White, MD, Terry Young, PhD

Sleep-Disordered Breathing Protocol Team: Christian Guilleminault, MD, Stuart Quan, MD, David White, MD

EEG/Neurocognitive Function Team: Jed Black, MD, Alan Gevins, DSc, Max Hirshkowitz, PhD, Gary Kay, PhD, Tracy Kuo, PhD

Mood and Sleepiness Assessment Team: Ruth Benca, MD, PhD, William C. Dement, MD, PhD, Karl Doghramji, MD, Tracy Kuo, PhD, James K. Walsh, PhD

Quality of Life Assessment Team: W. Ward Flemons, MD, Robert M. Kaplan, PhD

APPLES Secondary Analysis-Neurocognitive (ASA-NC) Team: Dean Beebe, PhD, Robert Heaton, PhD, Joel Kramer, PsyD, Ronald Lazar, PhD, David Loewenstein, PhD, Frederick Schmitt, PhD

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)

Michael J. Twery, PhD, Gail G. Weinmann, MD, Colin O. Wu, PhD

Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB)

Seven-year term: Richard J. Martin, MD (Chair), David F. Dinges, PhD, Charles F. Emery, PhD, Susan M. Harding MD, John M. Lachin, ScD, Phyllis C. Zee, MD, PhD

Other term: Xihong Lin, PhD (2 y), Thomas H. Murray, PhD (1 y).

Abbreviations

- AASM: American Academy of Sleep Medicine

- AHI: Apnea Hypopnea Index

- AIDS: Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- APPLES: Apnea Positive Pressure Long-term Efficacy Study

- BMI: Body mass Index

- CF: Cystic Fibrosis

- COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CPAP: Continuous positive airway pressure.

- EDS: Excessive daytime sleepiness

- EEG: Electroencephalogram

- ESS: Epworth sleepiness scale

- EMG: Electromyogram

- EOG: Electrooculogram

- FOSQ: Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire

- HRQoL: health related quality of life

- OSA: Obstructive Sleep apnea

- PSG: polysomnograpgy

- QALY: Quality Adjusted life years

- QoL: Quality of Life

- QWB: Quality of well being

- QWB-SA: Quality of well being-Self administered.

- SAQLI: Sleep apnea quality of life Index

- SD: Standard deviation

References

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. Sleep. 1999;22:667-89. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Young T, Peppard Pe Fau-Taheri S, Taheri S. Excess weight and sleep-disordered breathing. J Appl Physiol 2005;99:1592-9.(CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Dietz WH. The response of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to the obesity epidemic. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:575-96. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Franklin KA, Lindberg E. Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population-a review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:1311-22. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Health-Related-Quality-of-Life-and-Well-Being

- Yang EH, Hla KM, McHorney CA, Havighurst T, Badr MS, Weber S. Sleep apnea and quality of life. Sleep. 2000;23:535-41. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Epstein LJ, Kristo D Fau - Strollo PJ, Jr., Strollo PJ Jr, Fau-Friedman N, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:263-76. (PubMed]

- Windler S, Rowland S, Antic NA, et al. The effect of CPAP in normalizing daytime sleepiness, quality of life, and neurocognitive function in patients with moderate to severe OSA. Sleep. 2011;34:111-9. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- McArdle N, Kingshott R, Engleman HM, Mackay TW, Douglas NJ. Partners of patients with sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome: effect of CPAP treatment on sleep quality and quality of life. Thorax. 2001;56:513-8. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Kushida CA, Nichols DA, Quan SF, et al. The apnea positive pressure long-term efficacy study (APPLES): rationale, design, methods, and procedures. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:288-300. (PubMed]

- Frosch DL, Kaplan RM, Ganiats TG, Groessl EJ, Sieber WJ, Weisman MH. Validity of self-administered quality of well-being scale in musculoskeletal disease. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:28-31. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Kaplan RM, Sieber WJ, Ganiats TG. The quality of well-being scale: comparison of the interviewer-administered version with a self-administered questionnaire. Psychol Health. 1997;12:783-91. (CrossRef]

- Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Public Health Service,1968 - ci.nii.ac.jp

- Flemons WW, Buysse D, Redline S, Pack A. The report of American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. Sleep. 1999;22:667-89. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540-5. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Flemons W, Reimer MA. Development of a disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire for sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:494-503. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Kaplan RM, Anderson JP, Wu AW, Wm. Christopher M, Kozin F, Orenstein D. The quality of well-being scale: applications in AIDS, cystic fibrosis, and arthritis. Med Care. 1989;27:S27-S43. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Kaplan RM, Atkins CJ, Timms R. Validity of a quality of well-being scale as an outcome measure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37:85-95. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Frosch D, Porzsolt F, Heicappell R, et al. Comparison of German language versions of the QWB-SA and SF-36 evaluating outcomes for patients with prostate disease. Quality of Life Research. 2001;10:165-73. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Groessl EJ, Kaplan RM, Cronan TA. Quality of well-being in older people with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2003;49:23-28. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Baldwin CM, Griffith KA, Nieto FJ, O'Connor GT, Walsleben JA, Redline S. The association of sleep-disordered breathing and sleep symptoms with quality of life in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2001;24:96-105. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Fomas C, Ballester E, Arteta E, Ricou C, Diaz A, Fernandez A, Alonso J, Montserrat JM. Measurement of general health status in obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea patients. Sleep. 1995;18:876-79. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Anderson JP, Kaplan RM, Coons SJ, Schneiderman LJ. Comparison of the quality of well-being scale and the SF-36 results among two samples of ill adults: AIDS and other illnesses. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:755-62. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Munzenberger PJ, Van Wagnen CA, Abdulhamid I, Walker PC. Quality of life as a treatment outcome in patients with cystic fibrosis. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:393-8. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Saban KL, Stroupe KT, Bryant FB, Reda DJ, Browning MM, Hynes DM. Comparison of health-related quality of life measures for chronic renal failure: quality of well-being scale, short-form-6D, and the kidney disease quality of life instrument. Quality of Life Research. 2008;17:1103-15. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Terri EW, Cristina M, Greg M, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment of sleepy patients with milder obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186: 677-83. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Batool-Anwar S, Goodwin JL, Kushida CA, et al. Impact of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) on quality of life in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). J Sleep Res. 2016; 25:731-8. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Antic NA, Catcheside P, Fau-Buchan C, Buchan C, Fau-Hensley M, et al. The effect of CPAP in normalizing daytime sleepiness, quality of life, and neurocognitive function in patients with moderate to severe OSA. Sleep. 2011;34:111-9. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Jing J, Huang T, Cui W, Shen H. Effect on quality of life of continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a meta-analysis. Lung. 2008;186:131-44. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

- Billings ME, Rosen CL, Auckley D, et al. Psychometric performance and responsiveness of the functional outcomes of sleep questionnaire and sleep apnea quality of life index in a randomized trial: the HomePAP study. Sleep. 2014;37:2017-24. (CrossRef] (PubMed]

Cite as: Batool-Anwar S, Omobomi O, Quan SF. The effect of CPAP on HRQOL as Measured by the quality of Well-Being Self-Administered Questionnaire (QWB-SA). Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2020;20(1):29-40. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc070-19 PDF

Monday, April 6, 2020 at 10:41AM

Monday, April 6, 2020 at 10:41AM