Case Report: The Importance of Screening for EVALI

Wednesday, March 11, 2020 at 8:00AM

Wednesday, March 11, 2020 at 8:00AM Vanessa Josef MD, MS

George Tu, MD, FCCP

Department of Internal Medicine and Lung Center of Nevada

HCA MountainView Hospital

Las Vegas, Nevada, USA

Abstract

E-cigarette or vaping product use associated lung injury (EVALI) is an epidemic that has swept the United States by storm starting in Sept 2019. E-cigarettes or vaping was initially advertised as a “safer” alternative to smoking cigarettes when they entered the market in 2007. Only now are we are starting to see the complications of a not so harmless behavior. Many times, EVALI can present similar to community acquired pneumonia (CAP), which can cause a clinical conundrum when despite adequate antibiotic coverage, patients’ respiratory status tend to decline. Through our case report, we demonstrate and stress the importance of early screening for e-cigarette and vaping use in social history to increase clinical suspicion of EVALI and provide early intervention if a patient does not respond to CAP treatment, in hopes of identifying more cases of EVALI and igniting future research.

Introduction

The recent outbreaks of E-cigarette or vaping product use associated lung injury (EVALI) in Sept 2019, has placed the spotlight on the dangers of vaping. EVALI is a form of acute or subacute lung injury whose pathogenesis is unknown and is thought to be a spectrum of disease, rather than a single process. It has many findings such as organizing pneumonia, diffuse alveolar damage or acute fibrinous pneumonitis that are bronchiocentric and accompanied by bronchiolitis (1). If not identified quickly, EVALI has led to non-invasive ventilation, intubation and mechanical ventilation and even death in, otherwise, healthy young adults (1). The CDC confirmed 57 deaths and 2,602 reported cases of EVALI throughout the United States from Aug 2019 to Jan 2020, all of whom were between the ages of 18-34 (2,3). The paucity of knowledge within the medical community with regards to the disease, its pathogenesis and targeted treatment puts clinicians at a disadvantage. We report a case of a 30-year-old male who presented to our hospital with complaints of flu-like symptoms who was initially thought to have community acquired pneumonia but was later diagnosed with EVALI in order to raise awareness, illustrate how crucial screening can affect patient outcome and the need for further investigations of this severe respiratory illness.

Case Presentation

A 30-year-old Hispanic male with significant past medical history of intracranial hemorrhage secondary to arteriovenous malformation and craniotomy (2016) was admitted to our hospital in December 2019 after experiencing productive cough, subjective fevers, malaise, night sweats, dizziness, and fatigue for 3 days. He denied having any sick contacts or obtaining the flu vaccine, or any recent hospitalization. His admitting diagnosis was sepsis due to community acquired pneumonia and he was found to have acute renal failure which was pre-renal in nature.

Clinical findings on admission were as follows: body temperature 37°C, blood pressure 116/75mmHg, heart rate 129 beats/min, respiratory rate 18 breaths/min and oxygen saturation 99% on room air. Physical examination revealed diminished breath sounds on the right lower lobe upon auscultation. The patient’s breathing did not appear labored and he was able to speak full sentences. Laboratory tests revealed: white blood cell count of 13,000 x 109/L with 88.8% neutrophils, BUN/creatinine was 29/1.59 (elevated compared to last admission in 2016), urine toxicology was positive for cannabinoids, urinalysis showed proteinuria of 100 and the rest of the biochemical testing were within normal ranges.

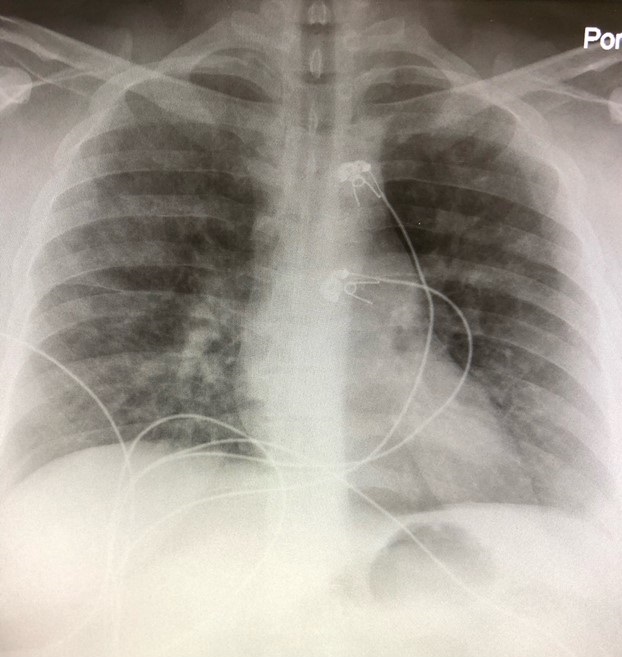

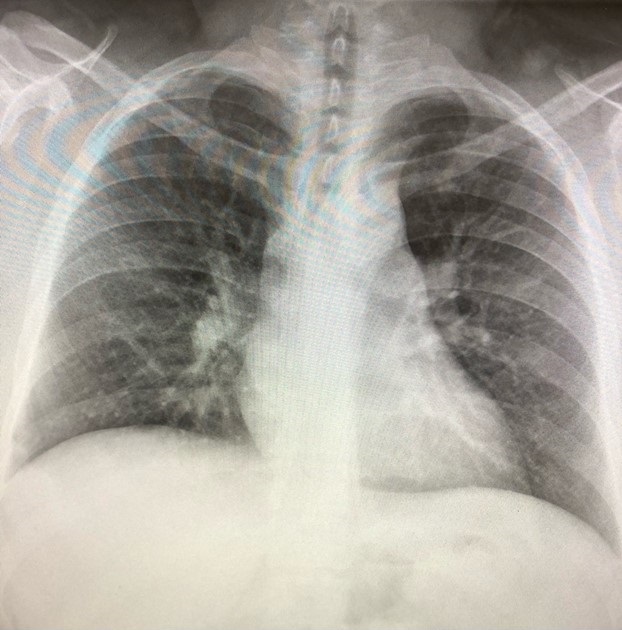

The initial chest x-ray (Figures 1 and 2) was read as interval development of interstitial type infiltrates in the perihilar and lower lobe distribution bilaterally, favoring pneumonia, compared to his pervious chest x-ray from 2016 which had no evidence of acute cardiopulmonary process (Figure 3).

Figures 1 and 2. Chest radiography (PA and lateral views) from the day of admission.

Figure 3. Chest radiograph from a previous admission in 2016 showing no acute cardiopulmonary process.

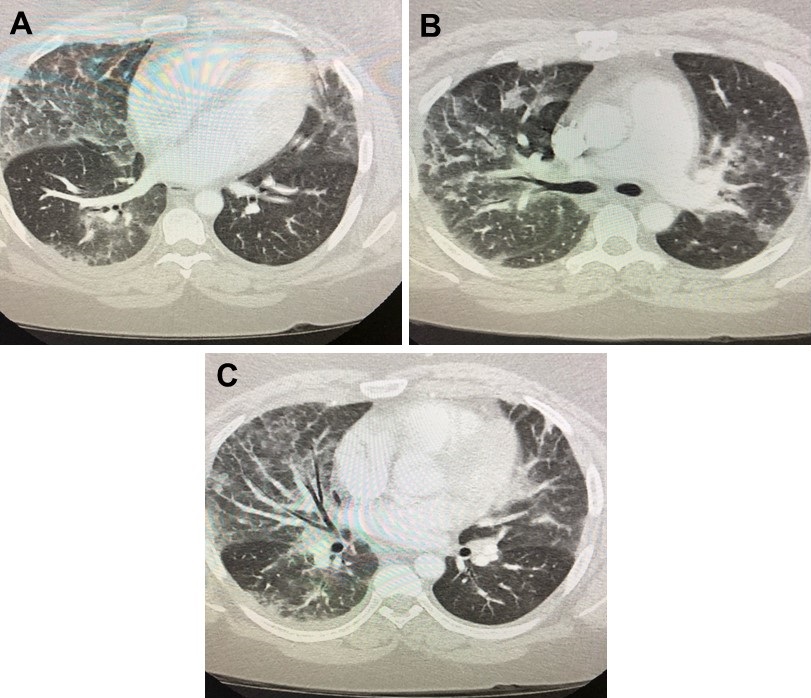

Sepsis bolus was given in the emergency department, blood cultures were drawn, and patient was started on ceftriaxone and azithromycin for community acquired pneumonia. Overnight, The patient spiked fever twice of 39°C at 2am and 4am the next morning. Antibiotics were broadened to vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam and blood cultures were repeated. Patient endorsed dyspnea and increased work of breathing requiring 2L nasal cannula. He remained tachycardic with his heart rate in the 110s despite adequate fluid resuscitation and antibiotic coverage. He also spiked an additional fever of 39.3°C at 8am. Arterial blood gas obtained showed pH 7.49, pCO2 33, pO2 70, HCO3 25 on 2L nasal cannula indicating acute hypoxic respiratory failure and respiratory alkalosis. Since renal function normalized, CT angiogram of the chest (Figure 4) was obtained. Although negative for pulmonary embolism, it showed extensive bilateral ground-glass lung opacities characteristic of pulmonary edema or pneumonia, noted predominantly in the lower and middle lung zones with sparing of the periphery.

Figure 4. CT angiography of the chest in lung windows, almost 24hrs after presentation to the emergency department.

Pulmonology was consulted. Upon further questioning it was discovered the patient has been vaping CBD oil and THC for about 5 years. He vapes approximately 1-2 dabbed cartridges per week which he normally obtains from a dispensary and his friends. The last time he vaped was 3 days prior to admission. He denied smoking tobacco, having a history of childhood asthma. He was started on methylprednisolone 40mg IV BID. Because his temperature became mildly elevated at 37.9°C in the afternoon, it was decided to take him for a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) the following day.

Respiratory viral panel, urine Legionella and urine Streptococcus pneumoniae, HIV 4th generation screen, sputum culture and blood cultures were all negative. Procalcitonin was 3.88 ng/ml. BAL cytology revealed non-specific pulmonary macrophages, benign bronchial epithelial cells, and mucus. It was negative for fungal organisms, cytomegalovirus, Mycoplasma, tuberculosis, Pneumocystis jirovecii, Legionella, and malignant cells. Gram stain was negative as well.

No other events occurred during the rest of his hospital course. Extensive counseling provided regarding cessation of vaping, which the patient expressed he will no longer do. His respiratory symptoms improved with the start of steroids and he was discharged on hospital day 6 with Augmentin and a 10-day prednisone taper.

Discussion

Currently, EVALI is a diagnosis of exclusion, rather than part of the initial screening for patients who present to the hospital with respiratory complaints. During our team’s initial assessment of the patient, vaping was not asked based off the reported history, imaging studies, and labs obtained by the emergency department because it appeared to be a straightforward case of sepsis secondary to community acquired pneumonia (CAP). However, despite adequate antibiotic coverage with ceftriaxone and azithromycin our patient continued to spike high fevers overnight. He did not have any risk factors for MRSA or Pseudomonas that would call for broad empiric coverage when he was first admitted based off the IDSA 2019 guidelines for treating CAP (7).

Despite sepsis fluid resuscitation, our patient remained tachycardic where his heart rate ranged between 110-120s. CT angiogram of the chest to rule out pulmonary embolism could not be done when he was admitted due to acute renal failure. A ventilation-perfusion scan would not be an appropriate study at the time due to patient’s abnormal chest x-ray. Thus, the details of the lung parenchyma could not be appreciated at the time of admission. With his continual fever spikes, we ordered the following labs to try and identify the type of infection, the possibility of a superimposed infection or resistance to the current antimicrobial regimen and if the patient was immunocompromised: flu antigens, urine Legionella and Streptococcus pneumoniae, respiratory viral panel (adenovirus, human metapneumovirus, influenza A & B, parainfluenza 1, 2 & 3, RSV, rhinovirus), HIV 4th generation screen, sputum culture, procalcitonin and repeat blood cultures. That same morning, his antibiotics were broadened to vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam.

Since the patient endorsed increased work of breathing and required 2L nasal cannula when he was initially on room air when he first arrived, pulmonary embolism (PE) had to be ruled out. With his renal function back to normal, we were able to get the CT angiogram of the chest which was negative for PE but showed the largely affected parenchyma. Pulmonology was consulted because of the irregular findings and sudden decline. Based off the peripheral sparing which is characteristic for EVALI and his urine toxicology testing positive for cannabinoids, further questioning about his social history was obtained. The patient’s admission to vaping THC and CBD oil for several years and that he obtains his cartridges from dispensaries and his friends, increased the suspicion for EVALI. Based on the current literature and reports from the CDC, EVALI is largely associated with the use of THC and products obtained from informal sources such as family/friends, dealers or online sellers (1). Many times, these unregulated products contain vitamin E acetate, which is currently thought to be the culprit ingredient igniting the destruction of lung parenchyma (4). The answer remains unclear if the cause of EVALI is an inhalation injury and/or is there an intrinsic reaction sparked by the chemical reactions between the various products that causes tissue injury.

He was immediately started on methylprednisolone 40mg IV BID, based on the recommended dosing of intravenous steroids of 1mg/kg (6). However, the patient’s temperature started to rise again despite the initiation of empiric antibiotics and steroids on the same day. BAL was performed the next morning to rule out infection, malignancy or any other structural issues and only revealed non-specific pulmonary macrophages, benign bronchial epithelial cells, and mucus. The patient clinically improved with the continued regimen of vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam and methylprednisolone IV.

There have been notable case reports with regards to EVALI that illustrate its various presentations and some of the barriers that make it difficult to diagnose. Salzman et al. (8) presented a case of a 27-year-old Caucasian female who developed acute eosinophilic pneumonia associated with electronic cigarettes. CBC at the time of admission showed WBC of 24,400 with 47% eosinophils. Although she admitted to vaping both nicotine and THC products for at least three years, three months prior to admission, she was vaping exclusively JUUL pods with nicotine blueberry and mint flavors. Her symptoms were severe enough that she required a one day stay in the ICU. She was treated with oral prednisone 50mg daily for a total of 5 days and oral doxycycline 100mg BID with improvement in her symptoms. This brings up the question whether her prior vaping history already jeopardized her lung parenchyma thus putting her at higher risk for developing EVALI.

In Schmitz’ (9) case report of a 38-year-old obese female with fibromyalgia on chronic prednisone (20mg daily), she admits to having started vaping CBD oil one month prior to admission. On BAL she was found to have diffuse upper and lower airway erythema with significant coughing, elevated eosinophil count (59%) and foamy macrophages which is associated with EVALI. She was started on methylprednisolone 1000mg daily, without antibiotics and experienced rapid improvement within a couple of days.

Works and Stack (5) discussed the case of a 20-year-old male who had several hospital admissions due to complaints of productive cough, high grade fever, gastrointestinal symptoms of diarrhea/nausea and 20lb unintentional weight loss over 3 weeks. The patient initially was treated at another hospital with ceftriaxone, levofloxacin and azithromycin and did not complete the course of antibiotics because they left against medical advice since they did not experience any improvement. On admission, the patient was found to have a very high leukocytosis with WBC of 44,800 and was not started immediately on empiric antibiotics. Instead, he was started on prednisone 1mg/kg and Bactrim after the BAL failed to yield an infectious cause. The patient was also noted to have obtain his THC cartridges from an outside source, like our patient.

Panse’s (10) case of a 25-year-old male who previously smoked 1-2packs per day and quit 6 months prior to admission was not forthcoming about vaping. Both CT scans showed multifocal ground-glass opacities with features of small airway obstruction. He underwent bronchoscopy and transbronchial biopsy which did not provide enough information to make a diagnosis. A video-assisted thorascopic lung biopsy was performed and showed acute and organized lung injury with interstitial edema, type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, alveolar fibrin deposition, acute fibrinous pneumonitis, lipid-laden macrophages and foci of organizing pneumonia consistent with EVALI. This is a prime example of how omission of vaping history delays diagnosis, leads to invasive procedures and although it did not happen in this particular situation, can result in death (10). Unlike the patient in Panse’s case, our patient easily admitted to vaping. Non-disclosure of medically relevant information such as vaping, is a problem clinicians will run into especially since it is a key piece of information needed to diagnose EVALI. Many patients withhold information from their doctors, especially those that they may find embarrassing, feel that they will be judge or lectured, or not wanting to hear about associated harm. Quantifying how many patients are withholding information or how many cases are not being accounted for because the person does not want to admit they are vaping would be difficult.

Formal diagnostic criteria for EVALI has not been agreed upon which can be attributed to the various forms of lung injury. We were able to diagnose our patient based of the suggested criteria of e-cigarette or vaping in the previous 90 days, lung opacities on chest x-ray or CT, exclusion of infection, and the absence of alternative diagnosis (cardiac, neoplastic or rheumatologic) (1). In a case series by Kalininskiy et al. (12), the University of Rochester Medical Center (Rochester, New York, USA) created a clinical practice algorithm to allow for the rapid identification of suspected EVALI based on history, clinical presentation and chest imaging, which is similar to the CDC however it focuses on vaping activity from the past 30 days rather than 90 days.

Currently, the treatment of EVALI is empiric antibiotics for community acquired pneumonia, systemic glucocorticoids in those with worsening symptoms, and supportive therapy with supplemental oxygen (6). In our case, the patient improved with the combination of vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam and methylprednisolone. The efficacy of systemic glucocorticoids is still unknown (1). However, it still remains unclear whether it was the combination of those specific antibiotics in conjunction with steroids, the combination of vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam only or solely systemic glucocorticoids. Since CAP is more common, it should not be overlooked and go untreated. Further investigation needs to be done for more targeted therapy.

The long-term effects of EVALI in those who were treated are still not well known. It is currently recommended for repeat imaging to determine if the treatment regimen was successful. However, many patients are lost to follow-up, as was the case for our patient due to lack of insurance.

Our case report illustrates how crucial early identification of EVALI affects patient care. It is imperative clinicians screen for the disease to prevent further complications. We recommend the following screening criteria: although the population greatly affected by the EVALI epidemic have been predominantly males between the ages of 18-34 (37% of the cases reported to the CDC as of Jan 14, 2020 are age 18-24, and 24% are 25-34, with a 66% male predominance) it should include all those who vape or use e-cigarettes regardless of age or gender as illustrated with the aforementioned case reports (13). Patients who presents with respiratory symptoms, especially if they are similar to pneumonia, such as dyspnea, increased work of breathing, fevers/chills, productive cough, chest pain, pleurisy, hemoptysis, and noted hypoxemia should be asked more than just smoking history with regards to cigarettes. They should be asked about prior E-cigarettes usage or vaping in the past, when was the last use, what kind of products were used and were they concentrated/dabbed and where it was obtained. Clinical suspicion should be increased if patients admit to THC or CBD use, but nicotine, flavorings and additives should not be disregarded. Urine drug screen should be ordered if there is a strong clinical suspicion, and the patient is denying prior THC use. EVALI has also been associated with gastrointestinal symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting. It is important to rule out infectious causes, by asking about sick contacts, recent hospitalizations, history of HIV and use of immunologic agents that can cause one to be immunocompromised. Patients should be screened about airway diseases such as asthma, COPD, and interstitial lung disease since they could have already caused chronic changes to lung parenchyma. There is still so much that the medical community does not know about EVALI. Further investigations still need to be pursued to improve the medical community’s diagnosis and treatment of this serious respiratory epidemic.

Disclaimer

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA and/or an HCA affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA or any of its affiliated entities.

References

- Layden JE, Ghinai I, Pray I, et al. Pulmonary illness related to e-cigarette use in Illinois and Wisconsin - final report. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 5;382(10):903-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control. Outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. January 17, 2020.Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html#key-facts (accessed 3/10/20).

- Ellington S, Salvatore PP, Ko J, et al. Update: product, substance-use, and demographic characteristics of hospitalized patients in a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury - United States, August 2019-January 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Jan 17;69(2):44-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, et al. Vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 20;382(8):697-705. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Works K, Stack L. E‐cigarette or vaping product‐use‐associated lung injury (EVALI): A case report of a pneumonia mimic with severe leukocytosis and weight loss. JACEP Open. 2020;1-3. [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllou GA, Tiberio PJ, Zou RH, et al. Vaping-associated acute lung injury: a case series. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Dec 1;200(11):1430-1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. an official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 1;200(7):e45-e67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzman GA, Alqawasma M, Asad H. Vaping associated lung injury [EVALI]: an explosive United States epidemic. Mo Med. 2019 Nov-Dec;116(6):492-6. [PubMed]

- Schmitz ED. Severe respiratory disease associated with vaping: a case report. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2019;19[3]:105-9.[CrossRef]

- Panse PM, Feller FF, Butt YM, Gotway MB. February 2020 imaging case of the month: an emerging cause for infiltrative lung abnormalities. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2020;20(2):43-58. [CrossRef]

- Levy AG, Scherer AM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Larkin K, Barnes GD, Fagerlin A. Prevalence of and factors associated with patient nondisclosure of medically relevant information to clinicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Nov 2;1(7):e185293. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalininskiy A, Bach CT, Nacca NE, Ginsberg G, Marraffa J, Navarette KA, McGraw MD, Croft DP. E-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (EVALI): case series and diagnostic approach. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Dec;7(12):1017-26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control. Outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. February 5, 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html#map-cases (accessed 3/10/20).

Cite as: Josef V, Tu G. Case report: the importance of screening for EVALI. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2020;20(3)87-94. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc012-20 PDF