Hasan S. Yamin, MD1

Feras Hawarri, MD1

Mutaz Labib, MD1

Ehab Massad, MD2

Hussam Haddad, MD3

Departments of 1Internal Medicine Pulmonary & Critical Care Division, 2Thoracic Surgery and 3Pathology

King Hussein Cancer Center

Amman, Jordan

Abstract

Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) is a rare pulmonary disease, where carcinoid tumorlets invade the pulmonary parenchyma and bronchioles. These nests of cells release a variety of mediators including bombesin and gastrin releasing peptide that cause heterogeneous bronchoconstriction, creating a mosaic appearance on chest imaging studies, especially on expiratory scans. Clinically patients usually have long standing symptoms of shortness of breath (SOB) and cough that are difficult to distinguish from asthma. In this article we describe a case of DIPNECH in a patient with several years’ history of SOB and cough, and review 179 cases of DIPNECH reported in the literature since 1992.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old, non-smoking lady was admitted to the hospital in preparation for bilateral mastectomy. She recently received a diagnosis of bilateral breast invasive ductal carcinoma grade 2, estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) positive in the left tumor but negative in the right tumor.

Her past medical history was significant for hypertension, long standing cough and dyspnea on exertion labeled as asthma poorly responsive to nebulizers. Socially, she was a house wife with no history of occupational exposure.

The patient was found to be tachypneic (respiratory rate 22 breaths/minute) and hypoxemic (oxygen saturation 86% on room air). Heart rate and blood pressure were within normal limits. She had bilateral decreased breath sounds and diffuse expiratory wheezes.

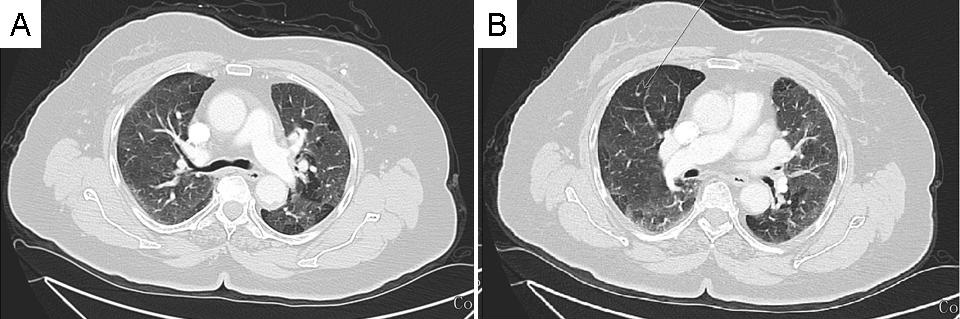

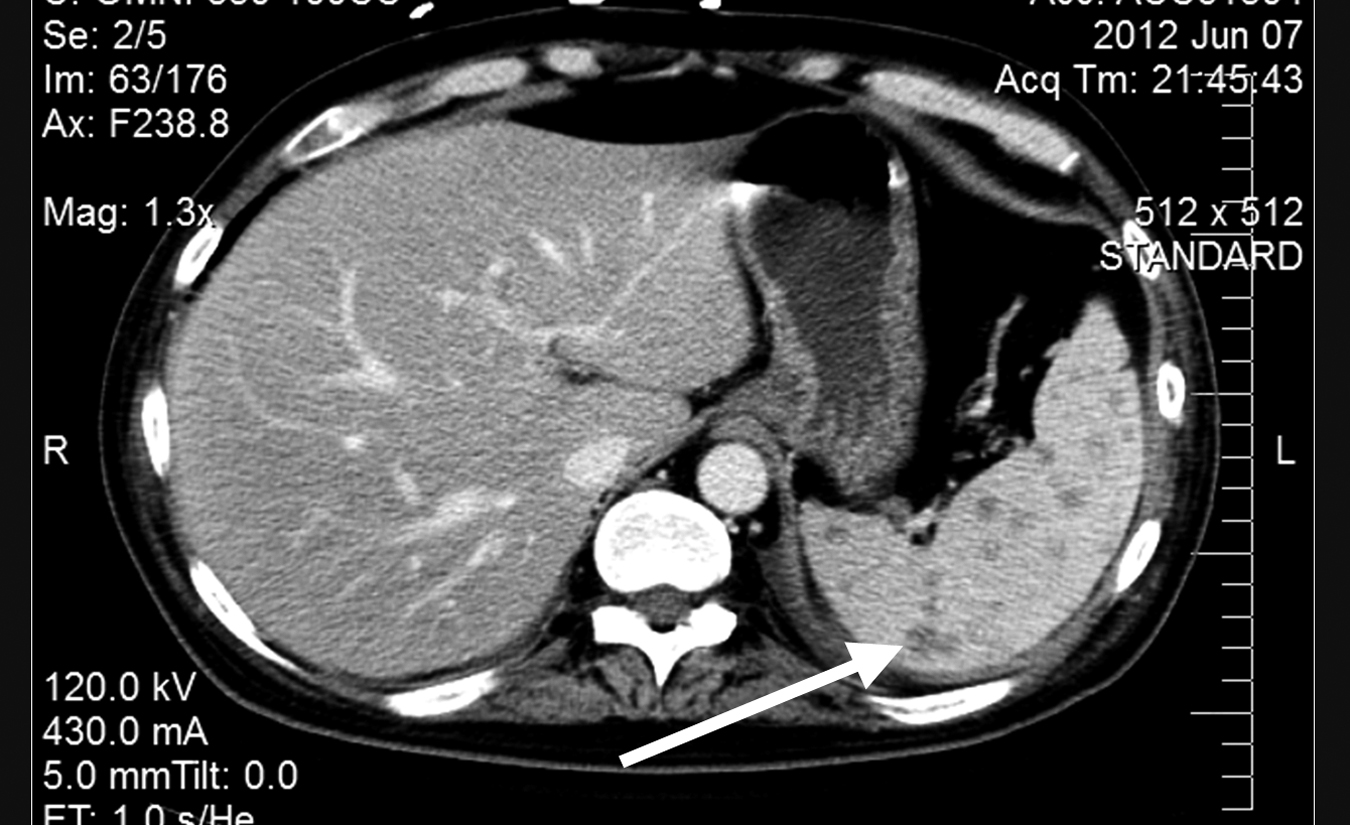

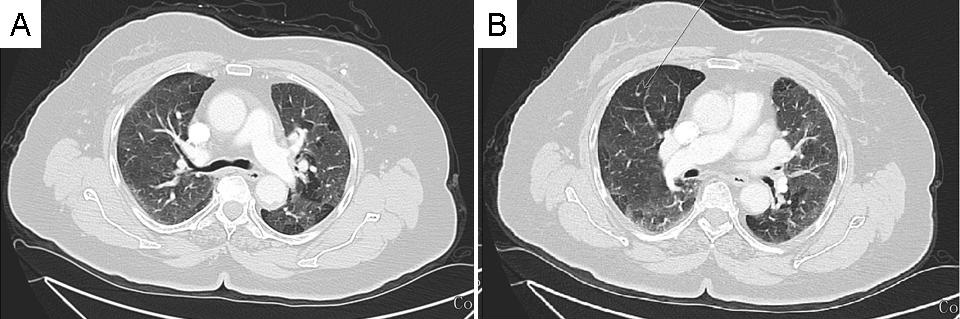

Chest CT scan revealed diffuse mosaic pattern and multiple pulmonary nodules in both lungs suggestive of metastases (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Representative images form chest CT scan showing a diffuse mosaic pattern and multiple pulmonary nodules in both lung fields suggestive of metastases.

These lesions did not take up fludeoxyglucose (FDG) on positron emission tomography (PET) scan. Her pulmonary function tests (PFT) were unremarkable except for reduction in expiratory reserve volume (ERV) at 22%, and increased residual volume to total lung capacity ratio (RV/TLC) at 136% probably related to air trapping. Diffusion lung capacity was within normal limits.

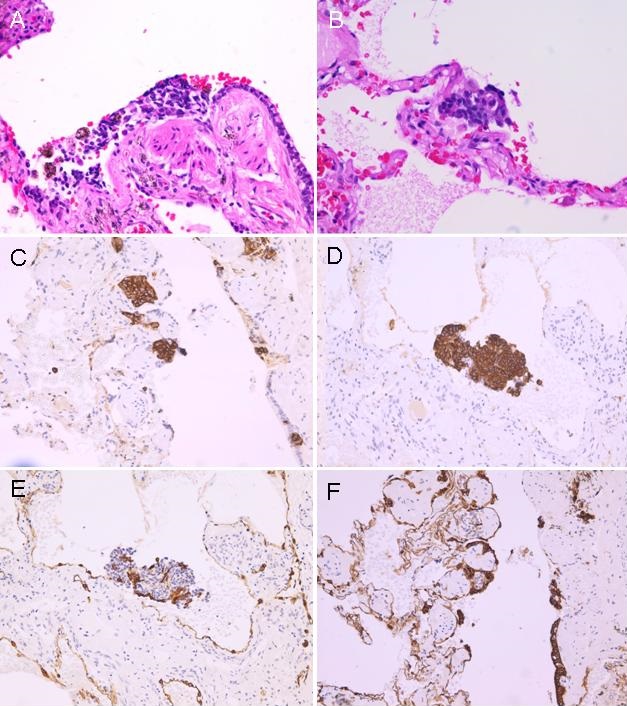

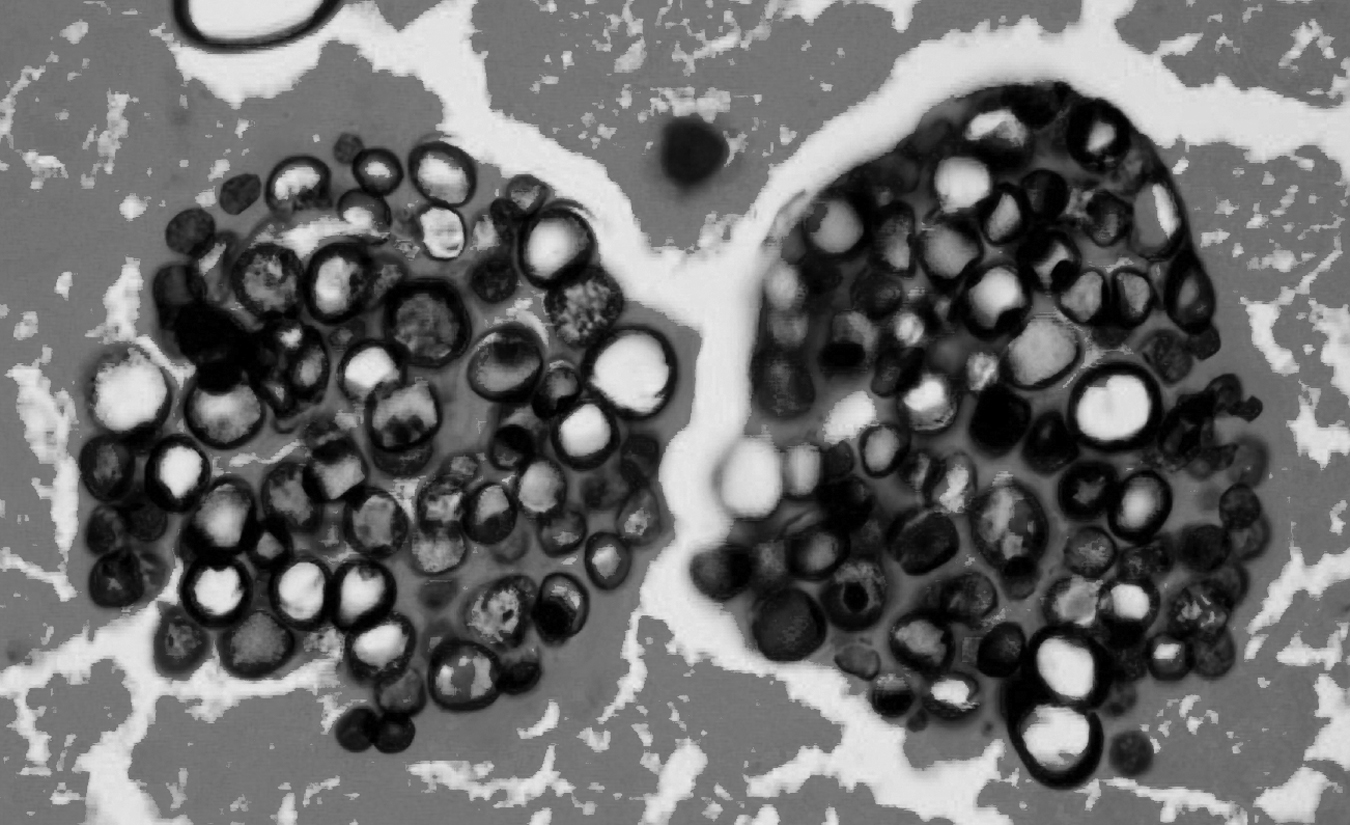

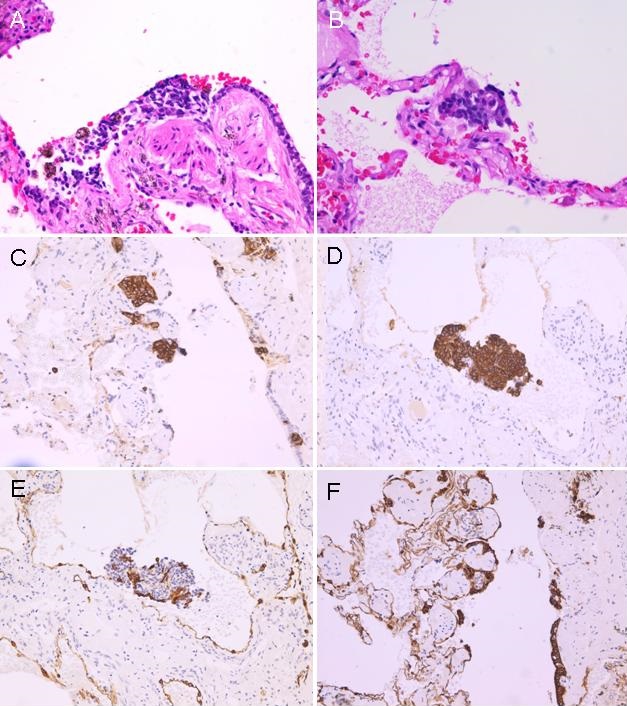

Video assisted thoracoscopic biopsy of one of the nodules in left lower lobe was done. Pathology showed both a carcinoid tumor and tumorlets invading lung bronchioles (Figure 2A & B) and these tumorlets were positive for chromogranin (Figure 2C & D) and pancytokeratin (Figure 2 E & F).

Figure 2. A & B: histology (H&E stain) showing carcinoid tumorlets invading lung bronchioles; C & D: positive staining for chromogranin; E &F: positive staining for pancytokeratin.

A diagnosis of diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) was made, and the patient was treated with intravenous steroids and nebulizers. Her oxygen saturation improved to 94% on room air. She was later discharged on oral steroids. Her CT scan also showed no significant improvement in changes described above.

Review of the Literature

Methods

We searched PubMed for all cases of diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia reported in the English literature since 1992 when the entity was first described. A total of 179 patients were identified in 55 articles, in the form of case reports and case series. In this article we contribute an additional patient (1-55).

Patient Characteristics

A total of 180 patients (including our patient) were identified. There were 161 females (89.5%) and only 19 males (10.5%). Mean age at diagnosis was 57.75 years (males tended to present at a younger age of 52 years, compared to 58.4 years in females). Most patients were never smokers 52.8%, smokers/exsmokers 27.2%, and in 20% smoking status was not mentioned.

The majority of patients presented with cough (91 patients, 50.5%), followed by exertional dyspnea (81 patients, 45%), and hemoptysis (6 patients, 3.3%). Incidental imaging findings led to diagnosis in 22 patients (12.2%). Mean duration of symptoms before diagnosis was 8.25 years (Table 1).

Table 1. Patients` characteristics and presenting symptoms.

Diagnosis, Therapy and Outcome

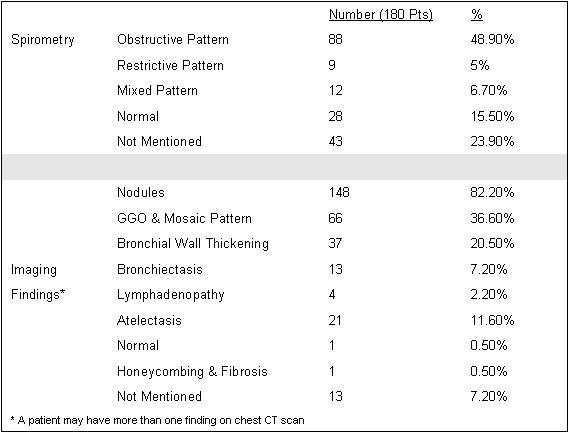

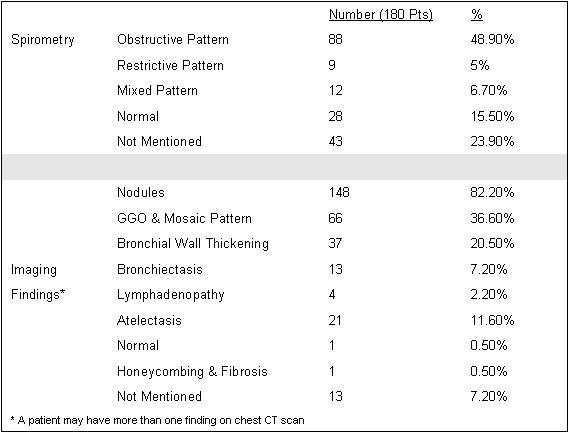

Most patients underwent imaging with chest CT scan, the most common findings were nodules in 148 patients (82.2%), ground glass opacities/mosaic pattern in 66 patients (36.6%), and bronchial wall thickening in 37 patients (20.5%). Most patients had an abnormal spirometry: obstructive pattern (48.9%), restrictive (5%), or mixed obstructive restrictive pattern (6.7%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Spirometry and imaging.

Because of their symptoms, and spirometry findings 45 patients (25%) were labeled with another disease including asthma in 29 patients (16.1%), COPD in 12 patients (6.6%) and bronchiolitis in 4 patients (2.2%).

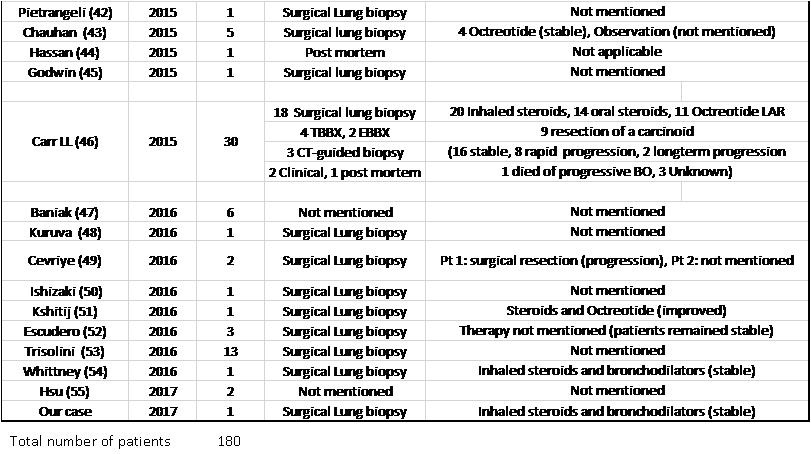

The diagnosis was made using surgical lung biopsy in 148 patients (82.2%), bronchoscopic biopsy in 10 patients (8 transbronchial biopsy, 2 endobronchial biopsy) (5.6%), CT-guided biopsy in 7 patients (3.9%), postmortem diagnosis in 3 patients (1.7%), post lung transplantation in 2 patients (1.1%) and clinically in 2 patients (1.1%). The diagnostic method was not mentioned in 8 patients (4.4%).

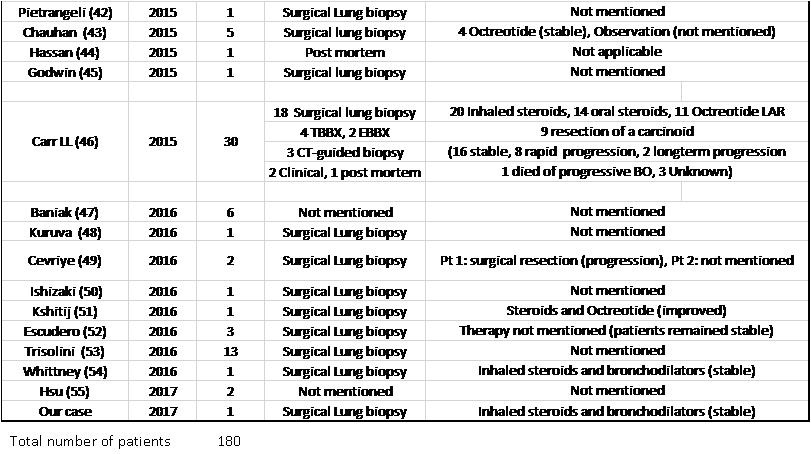

Patients received a variety of therapies including inhaled bronchodilators, inhaled or systemic steroids, and somatostatin analogues among others. Response to treatment was mentioned for 89 patients, (59 patients reported that their symptoms remained stable, 11 patients improved with treatment, while 18 patients reported symptom progression and 2 patients died. (Table 3).

Table 3. List of DIPNECH articles ordered by publication year. This table shows number of patients in each article, diagnostic method, therapy given and outcome.

Of note, 15 out of 23 patients who received a somatostatin analogue reported stable, or improvement in their symptoms (65.2%), which did not necessarily translate into improvement in air flows on spirometry (27, 29, 46, 51).

Discussion

Pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia was described early in the previous century (56), however the significance and role of the pathologic changes were not precisely determined. It was thought that they were secondary to other lung diseases such as interstitial lung disease, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, smoking exposure, or in people who live at high altitude. In addition to the previously mentioned associations, hyperplasia of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells was also thought to be a pre-neoplastic process, since the lesions can potentially progress to carcinoid tumors even without causing symptoms or airflow limitation. In 2004 the changes were recognized by WHO as one end of the spectrum of pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors.

The relationship between carcinoid tumorlets and other pulmonary diseases and its role in precipitating respiratory symptoms remains puzzling. The term DIPNECH was coined in 1992 by Aguayo (1) who described a new entity where idiopathic hyperplasia or dysplasia of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells occurred in the absence of other lung disorders. The changes were associated with physiologic and radiologic airflow limitation similar to obliterative bronchiolitis. This was the first description of pulmonary neuroendocrine hyperplasia as a primary process.

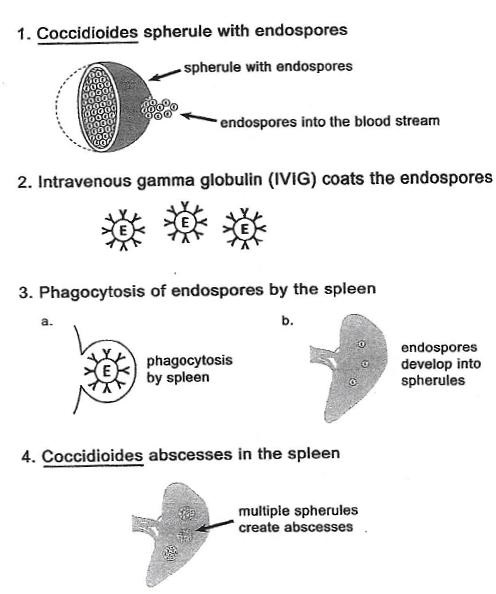

Because of similar symptoms, an obstructive pattern on pulmonary function tests, and chest imaging suggestive of air trapping, many patients receive a diagnosis of asthma for several years before the correct diagnosis is made. This similarity to other obstructive lung diseases can be explained by the pathologic changes of airway obstruction seen on biopsy. Pulmonary neuroendocrine cells, or Kulchitsky cells, are normally present in small numbers in airways, where they release a myriad of bioactive amines and peptides like serotonin, chromogranin A, gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP), and calcitonin.

Airway obstruction is believed to occur both due to physical obstruction of bronchioles by tumorlets and smooth muscle constriction caused by active mediators released. Bombesin and related peptides like gastrin releasing peptide, neuromedin B and neuromedin C are thought to cause bronchoconstriction indirectly through the release of several other bronchoconstrictors that act on smooth muscle cells (57). However, in vitro studies in guinea pig lungs suggest that bombesin may act directly by binding to specific receptors on smooth muscle cells (58).

Pulmonary neuroendocrine pathology occurs in a spectrum of three forms: hyperplasia, tumorlets and carcinoid tumors. DIPNECH is characterized by proliferation of neuroendocrine cells initially limited to the basement membrane of airways, when disease extends beyond the lumen of airway it is called carcinoid tumorlets. Tumorlets larger than 0.5 cm become carcinoid tumors and appear as nodules on chest CT scans. Diagnosis requires lung biopsy, with a surgical biopsy procedure more likely to provide diagnostic tissue than bronchoscopic transbronchial biopsies.

According to Aguayo`s definition of DIPNECH, patients have pulmonary symptoms with radiographic and physiologic abnormalities suggestive of obstructive lung disease, but in our review 12.2% of patients had no symptoms at all, and 15.5% had normal spirometry. We believe hyperplasia, tumorlets and carcinoid tumors represent different aspects of the same disease, the occurrence of symptoms, radiologic and physiologic airflow limitation depends on the time frame at which diagnosis was made, should those patients be followed up, they could develop symptoms and airflow limitation in the future. Thus, we propose to expand the definition to include patients with no symptoms or spirometry abnormalities. However, it remains uncertain whether asymptomatic patients who are diagnosed at an earlier stage need specific treatment or not.

It is also clinically difficult to establish a causal relationship, or determine the direction of the relationship between pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia and other concomitant lung disorders, or harmful exposures (1,59, 60). In our review 27.2% of patients were active or previous smokers, only one patient lived at high altitude (more than 2000m) (14), 29 patients had a history of previous or current malignancy including 8 lung cancers (not shown in table), 13 patients had evidence of bronchiectasis, and one patient had honeycombing on imaging. These findings are similar to data obtained from individual case reports and series (2, 6, 14, 17, 19, 22, 29, 33, 37, 46, 47 and 53).

When the diagnosis is made, therapeutic options may include observation for mild symptoms, inhaled or systemic steroids, in addition to bronchodilators, especially if patients who show reversible airway obstruction on PFT. Other potential therapies are somatostatin analogues, however more studies are needed to determine their precise role. (27, 29, 43, 46)

Conclusion

DIPNECH is a rare clinical entity that requires a high clinical suspicion. Because of clinical, spirometry, and imaging similarity to other obstructive lung diseases, and the requirement for lung biopsy to make the diagnosis, DIPNECH is probably an under-diagnosed entity, with still limited treatment options. The diagnosis should probably be considered in any patient with difficult to treat obstructive lung disease, unexplained bronchiolitis, particularly if there are multiple small lung nodules present on chest CT scan. We propose to expand the definition of DIPNECH to include patients with even no symptoms or spirometric evidence of airflow limitation, as development of these abnormalities depends on the time frame at which diagnosis is made. It is also difficult to establish a causal relationship with other concomitant lung conditions, the presence of which should not rule out a diagnosis of DIPNECH.

References

- Aguayo SM, Miller YE, Waldron JA, et al. Brief report: idiopathic diffuse hyperplasia of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells and airways disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1285-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller RR, Müller NL. Neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia and obliterative bronchiolitis in patients with peripheral carcinoid tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995 Jun;19(6):653-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armas OA, White DA, Erlandson RA, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell proliferation presenting as interstitial lung disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(8):963-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown MJ, English J, Muller NL. Bronchiolitis obliterans due to neuroendocrine hyperplasia: high-resolution CT–pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:1561-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehri M, Cutz E, Banzhoff A, et al. Hyperplasia of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells in a case of childhood pulmonary emphysema. Chest. 1997 Aug;112(2):553-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee JS, Brown KK, Cool C, et al. Diffuse pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: radiologic and clinical features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:180-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffini E, Bongiovanni M, Cavallo A, et al. The significance of associated pre-invasive lesions in patients resected for primary lung neoplasms. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26(1):165-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fessler MB, Cool CD, Miller YE, et al. Idiopathic diffuse hyperplasia of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells in a patient with acromegaly. Respirology. 2004;9(2):274-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmichael MG, Zacher LL. The demonstration of pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia with tumorlets in a patient with chronic cough and a history of multiple medical problems. Mil Med. 2005;170:439-441. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swigris J, Ghamande S, Rice TW, et al. Diffuse idiopathic neuropathic cell hyperplasia an interstitial lung disease with airway obstruction. J Bronchol. 2005;12:62-65. [CrossRef]

- Terminella L, Duarte A. Obliterative bronchiolitis due to diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia. Chest 2005; 128:467S–468S. [CrossRef]

- Adams H, Brack T, Kestenholz P, et al. Diffuse idiopathic neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia causing severe airway obstruction in a patient with a carcinoid tumor. Respiration. 2006;73(5):690-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johney EC, Pfannschmidt J, Rieker RJ, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia and a typical carcinoid tumor. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:1207-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes LJ, Majó J, Perich D, et al. Neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia as an unusual form of interstitial lung disease. Respir Med. 2007 Aug;101(8):1840-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhania N, Liang Q, Cool C, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) in a patient with cough and dyspnea resistant to standard therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:S173. [CrossRef]

- Ge Y, Eltorky MA, Ernst RD, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2007 Apr;11(2):122-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies SJ, Gosney JR, Hansell DM, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: an under-recognised spectrum of disease. Thorax. 2007 Mar;62(3):248-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqdah M, Jokhio S, El-zammar O. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine hyperplasia (DIPNECH). Chest 2007; 132:711S. [CrossRef]

- Warth A, Herpel E, Schmahl A, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) in association with an adenocarcinoma: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2008;2:21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coletta EN, Voss LR, Lima MS, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia accompanied by airflow obstruction. J Bras Pneumol. 2009; 35:489-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanaee MS, O'Byrne PM, Nair P. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine hyperplasia, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, and asthma. Eur Respir J. 2009; 34:1489-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim C, Stanford D, Young I, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: a report of two cases. Pathol Int. 2010; 60:538-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irshad S, McLean E, Rankin S, et al. Unilateral diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia and multiple carcinoids treated with surgical resection. J Thorac Oncol. 2010; 5:921-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenzinger A, Weichert W, Hensel M, et al. Incidental postmortem diagnosis of DIPNECH in a patient with previously unexplained 'asthma bronchiale'. Pathol Res Pract. 2010 Nov 15;206(11):785-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tippett V M, C G Wathen. Diffuse idiopathic neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: an unusual cause of breathlessness and pulmonary nodules. BMJ Case Rep. 2010 Dec 1;2010. pii: bcr0520103006. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron C M, Roberts F, Connell J, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: an unusual cause of cyclical ectopic adrenocorticotrophic syndrome. Br J Radiol. 2011 Jan;84(997):e14-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassar AA, Jaroszewski DE, Helmers RA, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: a systematic overview. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:8-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falkenstern-Ge RF, Kimmich M, Friedel G, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: 7-year follow-up of a rare clinicopathologic syndrome. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011 Oct; 137(10):1495-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorshtein A, Gross DJ, Barak D, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia and the associated lung neuroendocrine tumors: clinical experience with a rare entity. Cancer. 2012 Feb 1;118(3):612-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel C, Tirukonda P, Bishop R, Mulatero C, Scarsbrook A. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) masquerading as metastatic carcinoma with multiple pulmonary deposits. Clin Imaging. 2012 Nov-Dec;36(6):833-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoro Zulueta FJ, Martínez Prieto M, Verdugo Cartas MI, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia with multiple synchronous carcinoid tumors. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012 Dec;48(12):472-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker CM, Vummidi D, Benditt JO, et al. What is DIPNECH? Clin Imaging. 2012 Sep-Oct;36(5):647-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mireskandari M, Abdirad A, Zhang Q, et al. Association of small foci of diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Pathol Res Pract. 2013 Sep;209(9):578-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvořáčková J, Mačák J, Buzrla P. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: case report and review of literature. Cesk Patol. 2013 Apr; 49(2):99-102. [PubMed]

- Oba H, Nishida K, Takeuchi S, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia with a central and peripheral carcinoid and multiple tumorlets: a case report emphasizing the role of neuropeptide hormones and human gonadotropin-alpha. Endocr Pathol. 2013 Dec;24(4):220-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnatovskaia LV, Khoor A, Mira-Avendano I. Sarcoid-like reaction in diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014 Nov 15;190(10):e62-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ayoubi AM, Ralston JS, Richardson SR, Denlinger CE. Diffuse pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia involving the chest wall. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014 Jan;97(1):333-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killen H. DIPNECH presenting on a background of malignant melanoma: new lung nodules are not always what they seem. BMJ Case Rep. 2014 Feb 26;2014. pii: bcr2014203667. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou H, Ge Y, Janssen B, et al. Double lung transplantation for diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2014 Oct; 21(4):342-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdini F, Spaltro AA, Ruiu A, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) and multiple pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (PEH): a case report. Pathologica. 2015 Mar;107(1):37-42. [PubMed]

- Abrantes C, Oliveira RC, Saraiva J, et al. Pulmonary peripheral carcinoids after diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia and tumorlets: report of 3 cases. Case Rep Pulmonol. 2015;2015:851046. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrangeli V, Piciucchi S, Tomassetti S, et al. Diffuse neuroendocrine hyperplasia with obliterative bronchiolitis and usual interstitial pneumonia: an unusual "headcheese pattern" with nodules. Lung. 2015 Dec;193(6):1051-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan A, Ramirez RA. Diffuse Idiopathic Pulmonary Neuroendocrine Cell Hyperplasia (DIPNECH) and the role of somatostatin analogs: a case series. Lung. 2015 Oct;193(5):653-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan WA, Udaka N, Ueda A, et al. Neoplastic lesions in CADASIL syndrome: report of an autopsied Japanese case. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015 Jun 1;8(6):7533-9. [PubMed]

- Ofikwu G, Mani VR, Rajabalan A, et al. Case report: a rare case of diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia. Case Rep Surg. 2015;2015:318175. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr LL, Chung JH, Duarte Achcar R, et al. The clinical course of diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia. Chest. 2015 Feb;147(2):415-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baniak NM, Wilde B, Kanthan R. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH)--An uncommon precursor of a common cancer? Pathol Res Pract. 2016 Feb;212(2):125-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuruva M, Shah HR, Dunn AL, et al. 111In-Pentetreotide imaging in diffuse idiopathic neuroendocrine hyperplasia of the lung. Clin Nucl Med. 2016 Mar;41(3):239-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cansız Ersöz C, Cangır AK, Dizbay Sak S. Diffuse neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: report of two cases. Case Rep Pathol. 2016;2016:3419725. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizaki U, Itoh R, Matsuo Y, et al. Diffuse Idiopathic Pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: a case with long-term follow-up. J Thorac Imaging. 2016 Nov;31(6):W76-W79. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee K, Kamimoto JJ, Dunn A, et al. A case of DIPNECH presenting as usual interstitial pneumonia. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2016;84(3):174-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escudero AG, Zarco ER, Arjona JC. Expression of developing neural transcription factors in diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH). Virchows Arch. 2016 Sep;469(3):357-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trisolini R, Valentini I, Tinelli C, et al. DIPNECH: association between histopathology and clinical presentation. Lung. 2016 Apr;194(2):243-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren WA, Dalane SS, Warren BD, et al. Ten years of chronic cough in a 64-year-old man with multiple pulmonary nodules. Chest. 2016; 150(3):e81-e85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu J, Jia L, Pucar D, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia and granulomatous inflammation mimicking high-grade malignancy on FDG-PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2017 Jan;42(1):47-49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frölich F. Die Helle Zelle der Bronchialschleimhaut und ihre Beziehungen zum Problem der Chemoreceptoren. Frankf Z Pathol. 1949 Apr;60(3-4):517-59.

- Barnes PJ. Pharmacology of airway smooth muscle. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998 Nov;158(5 Pt 3):S123-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lach E, Haddad EB, Gies JP. Contractile effect of bombesin on guinea pig lung in vitro: involvement of gastrin-releasing peptide-preferring receptors. Am J Physiol. 1993 Jan; 264(1 Pt 1):L80-6. [PubMed]

- Campanha RB, Matos C, Nogueira F. DIPNECH (diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia): a rare syndrome or undiagnosed? J Pulm Respir Med 2015;5:4. [CrossRef]

- Aubry MC, Thomas CF Jr, Jett JR, et al. Significance of multiple carcinoid tumors and tumorlets in surgical lung specimens: analysis of 28 patients. Chest. 2007 Jun;131(6):1635-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Yamin HS, Hawarri F, Labib M, Massad E, Haddad H. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia in a patient with multiple pulmonary nodules: case report and literature review. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;15(6):282-93. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjcc139-17 PDF

Tuesday, January 2, 2018 at 8:00AM

Tuesday, January 2, 2018 at 8:00AM