Tip of the Iceberg: 18F-FDG PET/CT Diagnoses Extensively Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis with Cutaneous Lesions

Monday, July 10, 2017 at 10:05AM

Monday, July 10, 2017 at 10:05AM Benjamin B. Nia1

Emily S. Nia2

Ngozi Osondu3

John N. Galgiani3,4

Phillip H. Kuo2,5

1College of Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, USA.

2Department of Medical Imaging

3Department of Medicine, Section of Infectious Disease

4Valley Fever Center for Excellence

5Departments of Medicine and Biomedical Engineering

University of Arizona

Tucson, AZ, USA.

Abstract

We present a case of an immunocompetent 27-year-old African American man who was initially diagnosed with diffuse pulmonary coccidioidomycosis and started on oral fluconazole. While his symptoms improved, he began to develop tender cutaneous lesions. Biopsies of the cutaneous lesions grew Coccidioides immitis. Subsequent 18F-FDG PET/CT revealed extensive multisystem involvement including the skin/subcutaneous fat, lungs, spleen, lymph nodes, and skeleton. This case demonstrates the utility of obtaining an 18F-FDG PET/CT to assess the disease extent and activity in patients with disseminated coccidioidomycosis who initially present with symptoms involving only the lungs.

Report of Case

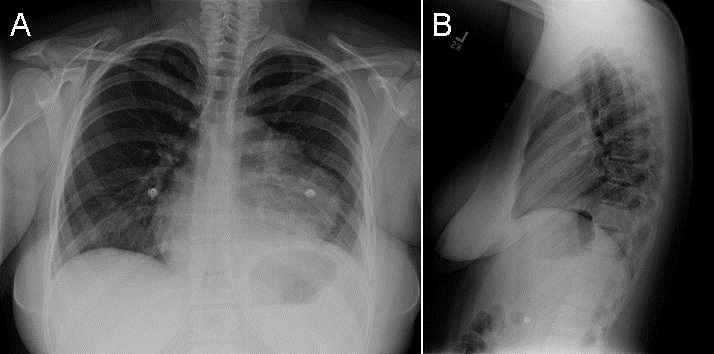

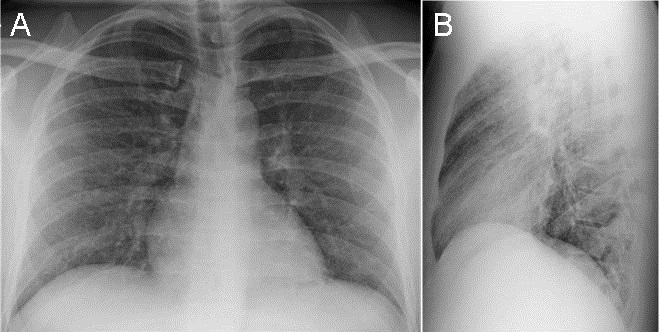

A 27-year-old African American man, who lived in the desert southwest of the United States for several years, with no significant past medical history presented with chest pain, weight loss, and shortness of breath. After two urgent care visits, he was admitted to the hospital with a chest radiograph showing bilateral pulmonary infiltrates (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Frontal (A) and lateral (B) chest radiography at hospital admission shows extensive reticulonodular opacities suspicious for atypical infection.

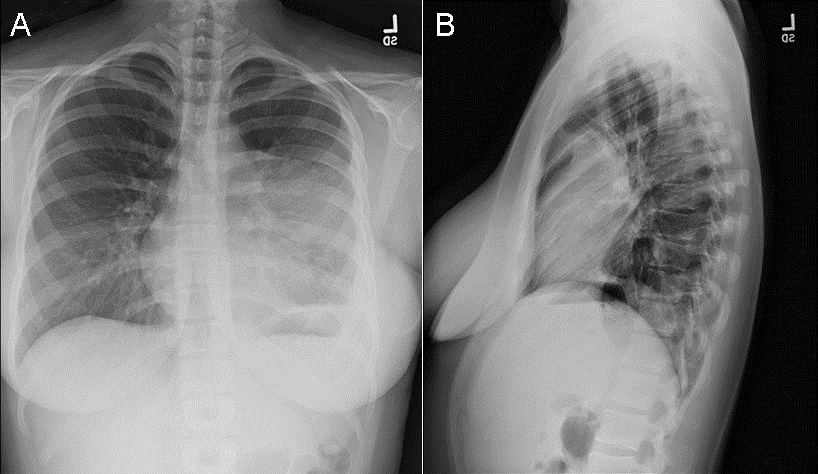

Bronchoscopy yielded Coccidioides spp., and immunodiffusion complement fixation (IDCF) was further confirmatory. Laboratory values showed elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and mildly abnormal liver function tests. He was diagnosed with diffuse pulmonary coccidioidomycosis and discharged home on 400 mg of oral fluconazole per day. At initial follow-up appointment, he reported feeling significantly better with resolution of his chest pain. He was gaining weight and had increased physical activities. At three-month follow-up, he reported continued improvement but complained of three new “spots” on the skin of his lower abdomen (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Photograph of the cutaneous lesions at nine months (red arrows) that were also present at 3- and 6-month follow-up appointments.

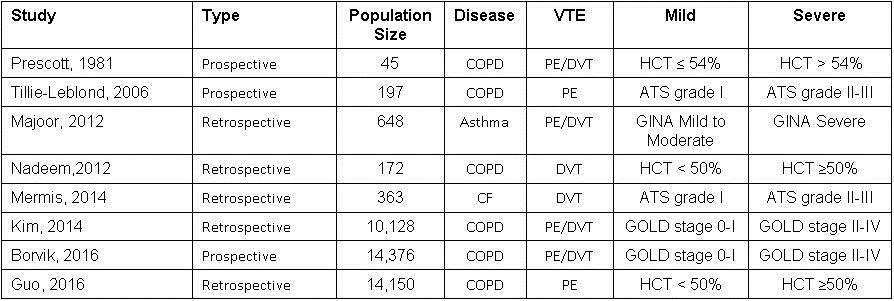

On physical exam, the cutaneous lesions were not suspicious for disseminated infection so treatment was continued unchanged. At six-month follow-up, he displayed numerous cutaneous lesions that were now tender. A biopsy of a cutaneous lesion demonstrated Coccidioides spherules on microscopy. An 18F-FDG PET/CT scan was performed to assess the extent of disease and demonstrated FDG-avid disease involving the skin/subcutaneous tissue, lungs, spleen, multi-station lymph nodes, and the skeleton (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Coronal maximum-intensity projection (A) and axial fused (B) 18F-FDG PET/CT scan shows FDG-avid disease involving the spleen (blue arrow), osseous structures (green arrows), multiple lymph nodes stations (yellow arrows), and soft tissues, including the skin and subcutaneous tissues (red arrows).

After another month, the skin lesions improved and, on further questioning, the patient revealed that he had previously not been taking his fluconazole as prescribed. Because of the skeletal involvement uncovered by the PET/CT scan, the patient’s oral fluconazole dose was increased to 800 mg per day. At nine-month follow-up, patient reported continued improvement and resolution of majority of skin lesions, albeit with residual hyperpigmentation.

Discussion

Coccidioidomycosis, or “Valley fever” is a fungal infection caused by inhalation of Coccidioides immitis or Coccidioides posadasii spores. Most infections cause little clinically apparent illness and result in lifelong immunity. Approximately one-third of infections produce pulmonary syndromes compatible with a community-acquired pneumonia, whereas <1% are complicated by potentially fatal blood-stream dissemination. Skin involvement is one of the most common manifestations of disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Other common sites of involvement include the bones, joints, and meninges. Unfortunately, nonspecific symptoms, the subacute nature of this disease, and lack of familiarity with this infection result in delayed diagnosis, increasing the risk of dissemination. Risk factors for disseminated coccidioidomycosis include African-American or Filipino ancestry, immunocompromised state, pregnancy, and discrete genetic defects. Coccidioides-endemic areas include parts of the southwestern United States, Central and South America (1,2).

18F-FDG PET/CT is an imaging modality most commonly utilized to stage malignancies and monitor response to therapy. 18F-FDG is a radioactive analog of glucose and is taken up by inflammatory cells. Detecting and monitoring infectious and inflammatory processes can be achieved with various imaging techniques, including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and ultrasonography. However, these techniques rely primarily on structural changes, and differentiation between active and indolent infections can be difficult. PET/CT’s whole-body coverage and high sensitivity can localize all sites of disease and assess level of disease activity (3,4).

This case demonstrates the utilization of 18F-FDG PET/CT to provide a comprehensive assessment of disease extent and activity in a patient with disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Diagnosing extent of disease is particularly important in this circumstance as osseous coccidioidomycosis predominantly results in osteolytic lesions that increase risk for fractures. Additionally, soft tissue assessment may reveal clinically occult soft tissue abscesses that may require surgical debridement (5). For this patient, the PET/CT scan results provided information that prompted medication dose escalation and emphasized the need for medication compliance. If disseminated coccidioidomycosis is suspected, PET/CT may provide value for the diagnostic evaluation in selected patients.

References

- Odio CD, Marciano BE, Galgiani JN, Holland SM.Risk factors for disseminated coccidioidomycosis, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 Feb;23(2). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen C, Barker BM, Hoover S, Nix DE, Ampel NM, Frelinger JA, Orbach MJ, Galgiani JN. Recent advances in our understanding of the environmental, epidemiological, immunological, and clinical dimensions of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(3):505-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang H, Alavi A. 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomographic Imaging in the Detection and Monitory of Infection and Inflammation. Semin Nucl Med. 2002;32:47-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu S, Chryssikos T, Moghadam-Kia S, Zhuang H, Torigian DA, Alavi A. Positron emission tomography as a diagnostic tool in infection: present role and future possibilities. Semin Nucl Med. 2009;39:36–51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta NA, Iv M, Pandit RP, Patel MR. Imaging manifestations of primary and disseminated coccidioidomycosis. App Radiol. 2015;44(2):9-21. Available at: http://appliedradiology.com/articles/imaging-manifestations-of-primary-and-disseminated-coccidioidomycosis (accessed 7/10/17).

Cite as: Nia BB, Nia ES, Osondu N, Galgiani JN, Kuo PH. Tip of the iceberg: 18F-FDG PET/CT diagnoses extensively disseminated coccidioidomycosis with cutaneous lesions. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;15(1):28-31. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc069-17 PDF