Safety and Complications of Bronchoscopy in an Adult Intensive Care Unit

Saturday, October 10, 2015 at 2:32PM

Saturday, October 10, 2015 at 2:32PM Aarthi Ganesh, MBBS1

Nirmal Singh, MBBS, MPH2

Gordon E. Carr, MD1

1Department of Pulmonary & Critical Care

2Department of Internal Medicine

University of Arizona

Tucson, Arizona

Abstract

Background: Bronchoscopy is a common procedure performed in adult intensive care units (ICU). However, very few studies report the safety and complications of the bronchoscopy and related procedures performed on critically ill patients. The primary aim of this study was to determine the incidence of complications following ICU bronchoscopy.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients admitted to an adult ICU and underwent bronchoscopy with or without bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and other bronchoscopic procedures. Data included patient demographics, APACHE II score, hemodynamics, comorbidities, type of ventilation and procedure performed. Data from BAL, including cellular differential and microbiology, were also collected.

Results: We identified 120 patient charts between November 2011 to March 2012. The most common procedure was bronchoscopy with BAL (62%) to evaluate for pneumonia (58%). Other procedures included transbronchial biopsy, APC and cryotherapy, balloon and stent placement, endobronchial biopsy and EBUS. Complications occurred in 18% of the patients, with hypoxia being the most common (7.5%). No deaths occurred related to the procedures. Nine percent of patients who had BAL or inspection had complications compared to 29% who underwent other procedures. Subgroup analysis conducted on patients undergoing BAL revealed significantly higher neutrophil counts (p=0.001) and higher APACHE II score (p=0.02) among those with BAL positive for bacteria and co-infection.

Conclusion: Bronchoscopy with BAL and inspection is relatively safe procedure even in critically ill patients. However, other interventional bronchoscopic procedures should be performed with caution in the ICU.

Abbreviations:

ICU: Intensive care unit

BAL: Bronchoalveolar lavage

EBUS: Endobronchial Ultrasound

APC: Argon Plasma Coagulation

SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure

CI: Confidence Interval

IP: Interventional pulmonary

MAP: Mean arterial pressure

SD: Standard deviation

CHF: Congestive heart Failure

COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

ILD: Interstitial Lung Disease

ET: Endotracheal

Introduction

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is a commonly performed procedure in the medical intensive care unit (ICU). Prior studies have indicated that bronchoscopy is generally safe, making it a relatively low-risk procedure in appropriately selected ICU patients (1-3). Most prior studies reporting the safety of bronchoscopy were performed in early 1990s. The rates of complications or adverse events in these earlier studies ranged from 2% to 40% (2,4-6). The primary aim of this study was to assess the incidence of complications in ICU patients undergoing bronchoscopy in the contemporary era.

Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Arizona. We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients, 18 years or older, admitted to the adult medical intensive care unit, who underwent bronchoscopy with or without bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and other bronchoscopic procedures from November 1, 2011 to March 31, 2012. The other bronchoscopic procedures included transbronchial biopsies, endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) guided biopsy, argon plasma coagulation (APC) and cryotherapy, balloon dilatation with stenting, and endobronchial biopsy. We excluded patients with incomplete charts, and patients who had bronchoscopy as a part of percutaneous tracheostomy procedure. Data included patient demographics, APACHE II scores, hemodynamics, co-morbidities, type of ventilation, type of procedure performed and the complications. Sedation used in the procedures included propofol or midazolam with fentanyl for analgesia. BAL results, including cellular differential and microbiology studies, were also collected. We used pre-specified definitions to assess for complications. We defined hypotension as reduction in systolic blood pressure (SBP) by >20 mm Hg or when a patient required vasopressors to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) > 60 mm Hg during or after the procedure. Hypoxia was defined by drop in saturation to < 90% or when the FiO2 requirement increased by > 20% for more than 2 hours after the procedure. Hemorrhage was indicated as per the procedure note by the bronchoscopist or when the note indicated use of epinephrine or when additional procedures needed to be performed to control the bleeding. During the procedure all the patients FiO2 was increased but was turned down to their previous ventilatory settings unless there was significant hypoxia.

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA/IC 13.1 (StataCorp LP, Texas). Numerical variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated where appropriate. Univariate comparisons between patients who did and did not develop complications were calculated using a χ2 test or Fischer's exact test for categorical variables and a 2-sample t test for continuous variables applying central limit theorem. All statistical testing was two-tailed with significance level set at the alpha level of ≤0.05.

Results

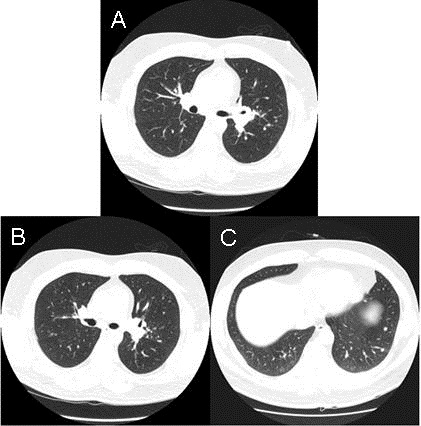

We identified 140 patients who underwent ICU bronchoscopy during the study period. Eighteen patients were excluded due to incomplete information. Two charts were excluded as the bronchoscopy was performed for percutaneous tracheostomy. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients undergoing ICU bronchoscopy.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Prior to Bronchoscopy

Key: CAD: Coronary Artery Disease

CHF: Congestive Heart Failure

COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

FiO2: Oxygen required

ILD: Interstitial Lung Disease

MAP: Mean arterial pressure

NM Disease: Neuromuscular disease

Sixty-nine percent of the patients were male and average age was 52 ± 16 years. The average APACHE II score was 18 ± 6 with a median of 18 and 88% of the patients were intubated and mechanically ventilated. The mean percentage oxygen (FiO2) requirement in the patients prior to the procedure was 63% ± 26. Sixty-three percent of the patients were immunocompromised, likely related to the large proportion of lung transplant recipients in our study population. Fifty-four percent also had chronic lung disease including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and interstitial lung disease (ILD). Other common co-morbidities included cardiovascular disease including congestive heart failure (CHF) and arrhythmias, malignancy and neuromuscular diseases. Table II shows the indications for ICU bronchoscopy. The most common indication for the procedure was to evaluate for pneumonia or infiltrate in 87 cases (72%), followed by atelectasis/ collapse/ secretions in 19 cases (15.8%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Indications For Procedures

Other indications included tracheal or airway diseases, which included tracheal stenosis, upper airway obstruction, tracheal mass and bronchopleural fistula in 11 (8%) and hemoptysis (2%). The most common procedures performed were bronchoscopy with BAL in 75 (62%) and inspection in 31 (26%) (Table 3).

Table 3. Procedures

Key: APC: Argon plasma coagulation

BAL: Bronchoalveolar lavage

Cryo: Cryotherapy

EBUS: Endobronchial ultrasound

ET: Endotracheal tube

Other procedures included transbronchial biopsy, APC and cryotherapy, balloon and stent placement, endobronchial biopsy and EBUS.

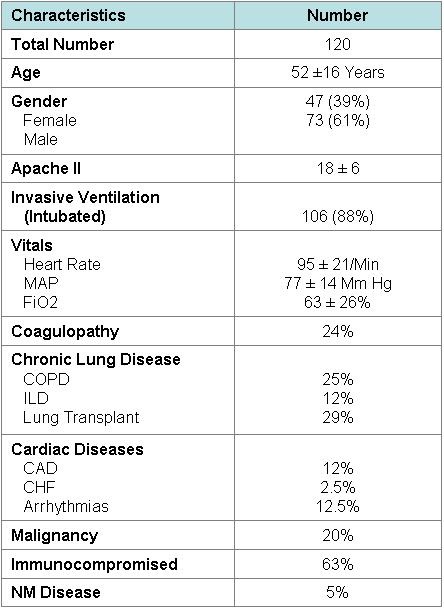

Table 4 shows the complications resulting from ICU bronchoscopy in this study population.

Table 4. Complications

Twenty two complications occurred during or within 2 hours after the procedure (18%), with hypoxia being the most common (7.5%). Hypoxia in two patients occurred secondary to hemorrhage. Pneumothorax was seen in one patient who underwent transbronchial biopsy with no fluoroscopic guidance. Hypotension which needed treatment with fluids or vasopressors occurred in 5.8% and hemorrhage in 3.3%. Hemorrhage was unrelated to coagulopathy in the patients. Significant bradycardia requiring treatment with atropine occurred in one patient. No deaths were reported related to the procedures. None of the procedures had to be terminated secondary to the complications. More adverse events were seen among the patients who underwent other bronchoscopic procedures (29%) than those undergoing BAL or inspection only (9%), though this was not statistically significant (p = 0.07).

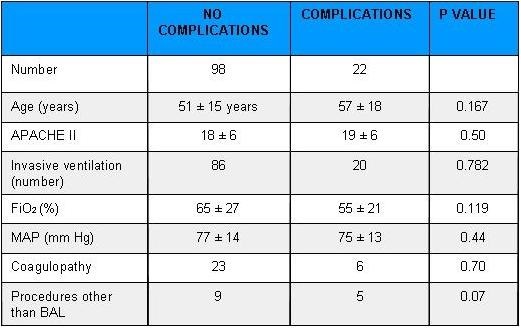

As depicted in Table 5, none of the complications were significantly affected by the underlying comorbidities or the APACHE scores.

Table 5. Patient Characteristics Stratified by Complications

Key: BAL: Bronchoalveolar lavage

MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure

Complications were not significantly associated with the amount of oxygen required (FiO2) and the mode of ventilation which the patients were on prior to the procedure. Similarly, neither the mean arterial pressure before the procedure or coagulopathy influenced the rate of complications. Hospital mortality was not different in the group with or without complications.

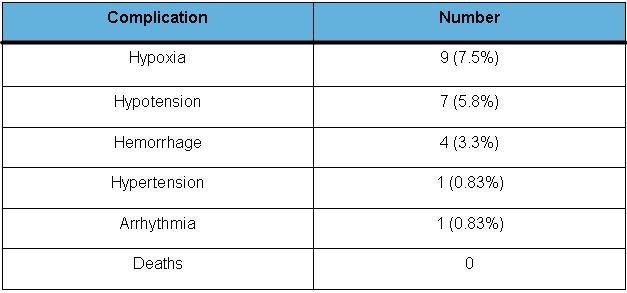

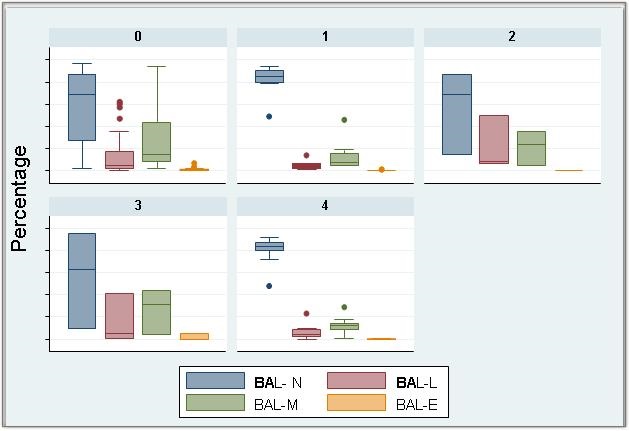

Figure 1 and Table 6 show the BAL cell differential.

Figure 1. BAL differential in culture with normal respiratory flora (0), bacteria (1), Viral (2), Fungal (3) and Co-infection (4). Each bar represents the differential in percentage.

Key: BAL: Bronchoalveolar lavage

BAL N: Neutrophil count in BAL (in percentage)

BAL L: Lymphocyte count in BAL (in percentage)

BAL M: Macrophages count in BAL (in percentage)

BAL E: Eosinophils count in BAL (in percentage)

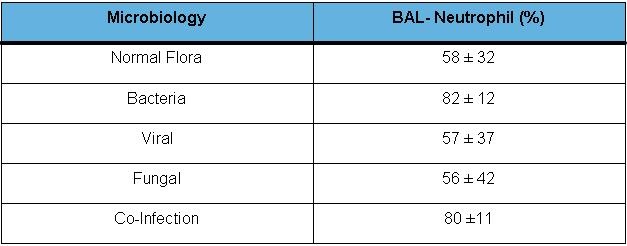

Table 6. Bronchoalveolar Lavage Differential

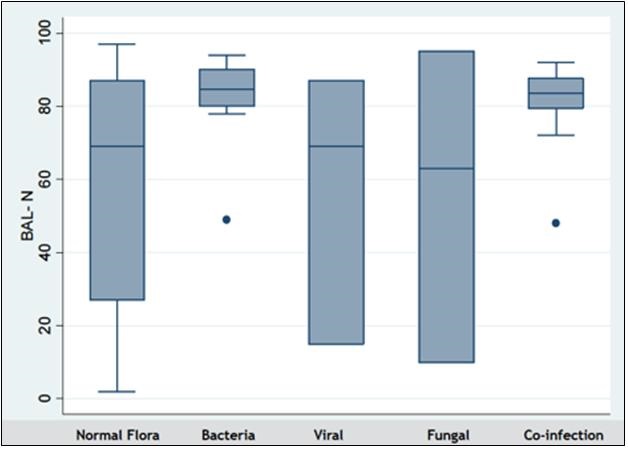

Patients found to have bacterial pneumonia or mixed viral and bacterial infection had significantly higher neutrophil counts (mean BAL neutrophil count 82% for bacterial infection, and 80% for co-infections) than other patients (p=0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Neutrophil predominance in bacterial pneumonia. KEY: BAL-N: Bronchoalveolar lavage, neutrophil differential (in percentage).

These patients also had a higher APACHE II score (p=0.02). Hospital mortality was higher among those with BAL positive for bacteria (p= 0.012). Mortality was also significantly higher among patients with underlying malignancy (p= 0.002).

Discussion

In our study of 120 ICU bronchoscopies, we found a complication rate of 18%. No deaths were observed in this study. Hypoxia was the most common adverse event in our study, occurring in 9 procedures (7.5%) as has been noticed in the previous studies. Introduction of a bronchoscope through an endotracheal (ET) tube is known to cause airway obstruction resulting in increasing intra-tracheal pressures and variation in respiratory physiology (6). Almost all the patients who were mechanically ventilated had a size 7.5 - 8.5 ET tube or had tracheostomy in place. As in prior studies, BAL performed for evaluation of pneumonia and atelectasis were the two most common indications of the procedure (72% and 15.8% respectively) in our study (1-7). Even though bronchoscopy has not shown to be routinely superior to chest physiotherapy, certain subset of patient population may benefit from it (3,8,9). Improvement in oxygenation has been shown to occur in certain earlier studies (10,11).

Hypotension is also a known complication occurring during bronchoscopy. Our study had 7 events (5.8%) of hypotension needing vasopressor or fluid infusion. This was likely related to the sedation. Hypertension was observed in one case and bradycardia requiring treatment was seen in one. Cardiovascular abnormalities associated with bronchoscopy is generally related to the sympathetic surge happening during the procedure and the hypoxia (12-14). Per earlier studies, the complication rate of transbronchial biopsies in mechanically ventilated patients range between 0-15% (15,16,17). But it is relatively safe in comparison to open lung biopsy.

With the advent of newer technology, there has been an increase in the number of other bronchoscopic interventional pulmonary (IP) procedures, including endobronchial ablative therapies such as APC and cryotherapy. Endobronchial lesions occupying more than 50% of the airway lumen can alter the airway physiology and result in hypoxia, ventilation perfusion mismatch and hence respiratory failure. Use of ablative therapies can potentially reverse this (18). APC has been an useful tool to remove endobronchial lesions and relieve obstruction. It has been shown to be efficient and relatively safe in outpatient setting, but APC on mechanically ventilated patients has not been very well studied (19). APC in mechanically ventilated patient requires decrease in the FiO2 to less than or equal to 40%. Complications related to IP procedures performed specifically in patients requiring mechanical ventilation are difficult to assess from the available literature (20). However, given the complexity of these cases and underlying illness, usually the complications are minor. In our study, interventional bronchoscopy procedures like APC, cryotherapy was to relieve airway obstruction which was the cause of mechanical ventilation. In our study, APC case was associated with hemorrhage. The balloon dilatation and stenting which was performed for a case of tracheal stenosis arising from malignancy. This was not associated with any complications related to the procedure in our study. Further study is needed to refine our understanding of the risks of advanced bronchoscopic techniques in ICU patients.

Procedures like EBUS are usually not done in critically ill patients. There are no studies which have looked into the use of and complications of performing EBUS in critically ill patients. Bhaskar et al. (21) report the use of esophageal access for mediastinal sampling through EBUS in ICU patients for the reason of causing hypoxia and changes in airway physiology with the EBUS scope in airway. Our study had one patient who had an EBUS for lung mass and this was not associated with any complications.

Subgroup analysis in our study showed the presence of neutrophilic predominance with neutrophil count of >80% in the BAL differential in patients diagnosed with bacterial infections and co-infections compared to those with viral/ fungal or mixed flora (p=0.001). This was similar to results from earlier studies (22,23). Neutrophilic pleocytosis in BAL fluid is frequently found in patients with pneumonia. As the neutrophil count is higher in bacterial pneumonia, it can indicate towards a differential of bacterial pneumonia even prior to the final microbiology results. Hence BAL differential may be complimentary to final culture results and maybe helpful to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in critically ill patients. Mortality among critically ill patients with bacterial pneumonia was higher compared to others (p=0.012). These patients tend to be sicker with higher APACHE II scores.

The weaknesses of the study includes the fact that it was retrospective chart review. The total number is small, and the number of the IP procedures performed is even smaller. Hence it is important that more studies should be conducted looking into the safety and complications of IP procedures in critically ill patients.

Conclusion

Our study looked into the fiberoptic bronchoscopy with BAL and inspection as well as other therapeutic procedures done in the critically ill patients. It indicates that even in critically ill patients, bronchoscopy with inspection and BAL is safe. Other interventional pulmonary procedures may have more complications. Even though the number of IP procedures performed in the study is low, the evidence of slightly more number of complications with these procedures indicates the need for caution before attempting them in the critically ill patients.

References

-

Barrett CR Jr. Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy in the critically ill patient. Methodology and indications. Chest. 1978;73(5 Suppl):746-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Hertz MI, Woodward ME, Gross CR, Swart M, Marcy TW, Bitterman PB. Safety of bronchoalveolar lavage in the critically ill, mechanically ventilated patient. Crit Care Med. 1991;19(12):1526-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Olopade CO, Prakash UB. Bronchoscopy in the critical-care unit. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64(10):1255-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Steinberg KP, Mitchell DR, Maunder RJ, Milberg JA, Whitcomb ME, Hudson LD. Safety of bronchoalveolar lavage in patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148(3):556-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Prebil SE, Andrews J, Cribbs SK, Martin GS, Esper A. Safety of research bronchoscopy in critically ill patients. J Crit Care. 2014;29(6):961-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Guerreiro da Cunha Fragoso E, Gonçalves JM. Role of fiberoptic bronchoscopy in intensive care unit: current practice. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2011;18(1):69-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Raoof S, Mehrishi S, Prakash UB. Role of bronchoscopy in modern medical intensive care unit. Clin Chest Med. 2001;22(2):241-61, vii. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Kreider ME, Lipson DA. Bronchoscopy for atelectasis in the ICU: a case report and review of the literature. Chest. 2003;124(1):344-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Marini JJ, Pierson DJ, Hudson LD. Acute lobar atelectasis: a prospective comparison of fiberoptic bronchoscopy and respiratory therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;119(6):971-8. [PubMed]

-

Snow N, Lucas AE. Bronchoscopy in the critically ill surgical patient. Am Surg. 1984;50(8):441-5. [PubMed]

-

Stevens RP, Lillington GA, Parsons GH. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy in the intensive care unit. Heart Lung. 1981;10(6):1037-45. [PubMed]

-

Katz AS, Michelson EL, Stawicki J, Holford FD. Cardiac arrhythmias. Frequency during fiberoptic bronchoscopy and correlation with hypoxemia. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141(5):603-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Lindholm CE, Ollman B, Snyder JV, Millen EG, Grenvik A. Cardiorespiratory effects of flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy in critically ill patients. Chest. 1978;74(4):362-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Trouillet JL, Guiguet M, Gibert C, Fagon JY, Dreyfuss D, Blanchet F, Chastre J. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy in ventilated patients. Evaluation of cardiopulmonary risk under midazolam sedation. Chest. 1990;97(4):927-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Bulpa PA, Dive AM, Mertens L, Delos MA, Jamart J, Evrard PA, Gonzalez MR, Installé EJ. Combined bronchoalveolar lavage and transbronchial lung biopsy: safety and yield in ventilated patients. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(3):489-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

O'Brien JD, Ettinger NA, Shevlin D, Kollef MH. Safety and yield of transbronchial biopsy in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(3):440-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Casal RF, Ost DE, Eapen GA. Flexible bronchoscopy. Clin Chest Med. 2013;34(3):341-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Seaman JC, Musani AI. Endobronchial ablative therapies. Clin Chest Med. 2013;34(3):417-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Morice RC, Ece T, Ece F, Keus L. Endobronchial argon plasma coagulation for treatment of hemoptysis and neoplastic airway obstruction. Chest. 2001;119(3):781-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Boyd M, Rubio E. The utility of interventional pulmonary procedures in liberating patients with malignancy-associated central airway obstruction from mechanical ventilation. Lung. 2012;190(5):471-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Bhaskar N, Shweihat YR, Bartter T. The intubated patient with mediastinal disease--a role for esophageal access using the endobronchial ultrasound bronchoscope. J Intensive Care Med. 2014;29(1):43-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Stolz D, Stulz A, Müller B, Gratwohl A, Tamm M. BAL neutrophils, serum procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein to predict bacterial infection in the immunocompromised host. Chest. 2007;132(2):504-14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Choi SH, Hong SB, Hong HL, Kim SH, Huh JW, Sung H, Lee SO, Kim MN, Jeong JY, Lim CM, Kim YS, Woo JH, Koh Y. Usefulness of cellular analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for predicting the etiology of pneumonia in critically ill patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97346. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Ganesh A, Singh N, Carr GE. Safety and complications of bronchoscopy in an adult intensive care unit. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2015;11(4):156-66. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc106-15 PDF