Christopher Strawter, MD

Pedro Quiroga, MD

Syed Zaidi, MD

Thomas Ardiles, MD

Maricopa Medical Center

Phoenix, Arizona

Abstract

The differential diagnosis of multiple pulmonary nodules is large and includes congenital and inherited disorders, malignancy, infectious etiologies, noninfectious granulomatous and inflammatory conditions,among many others. Diagnostic evaluation is aided by attention to extrapulmonary symptoms and features. We herein describe an unusual case of multiple pulmonary nodules attributed to cysticercosis and present a discussion of pathophysiologic changes related to medications and highlight the diagnostic value of extrapulmonary cutaneous features.

Case Report

History of Present Illness

A 31-year-old incarcerated Hispanic male presented with a nonproductive cough for several months and one episode of blood tinged sputum. He admitted to weight loss and night sweats, headaches, and visual disturbances. He was an immigrant from Honduras and lived in Arizona for the past 15 years. He had chronic hepatitis C infection and was receiving treatment with pegylated interferon-alfa-2a (IFN-α) and ribavirin. His symptoms began one month after initiating antiviral therapy.

Physical Exam

On admission, his vital signs were stable. Several mobile one cm cutaneous and subcutaneous nodules were palpable on the trunk and neck. Lymphadenopathy was not present. The neurological exam revealed diplopia upon lateral gaze. The cardiopulmonary exam was unremarkable.

Laboratory Data

Routine hematology work-up revealed leukopenia (2.3 x 103/µL), neutropenia (1.4 x 103/µL) without eosinophilia. AST and ALT were 239 U/L and 265 U/L respectively. Quantiferon TB and coccidioidomycosis tests were negative.

Radiology

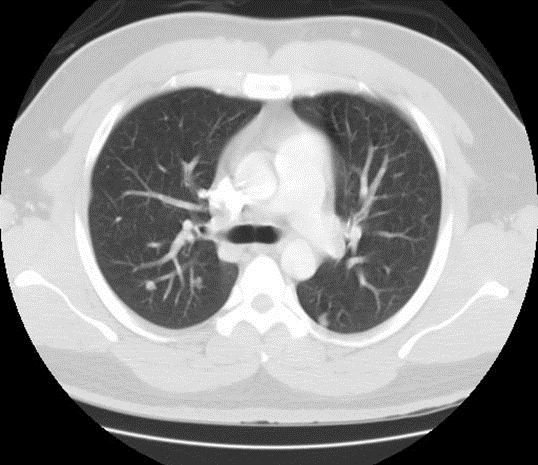

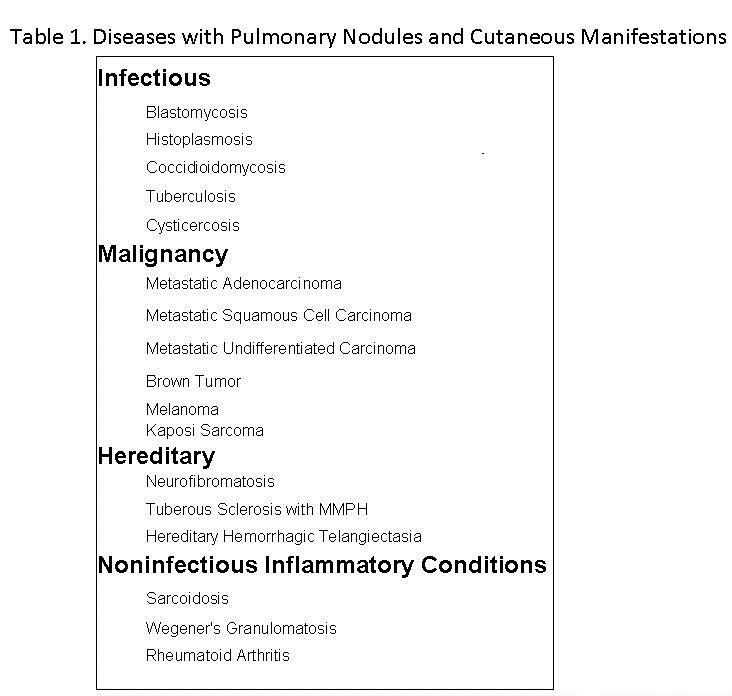

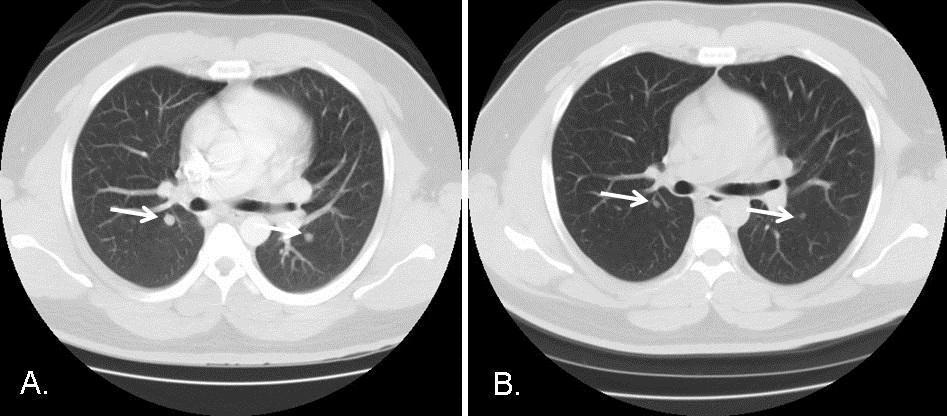

Plain radiograph of the chest was unremarkable. Computed Tomography (CT) of the chest demonstrated multiple bilateral well defined nodules ranging in size from 7.2 mm to 11mm in diameter involving lung parenchyma and chest wall soft tissue structures (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Computed tomography (CT) chest lung window. Seen here are multiple, bilateral, well defined nodules involving the lung parenchyma and subcutaneous tissue.

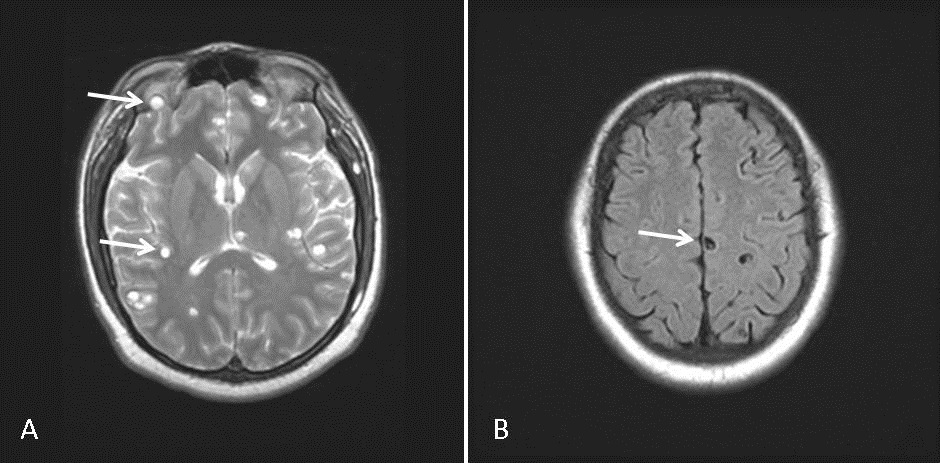

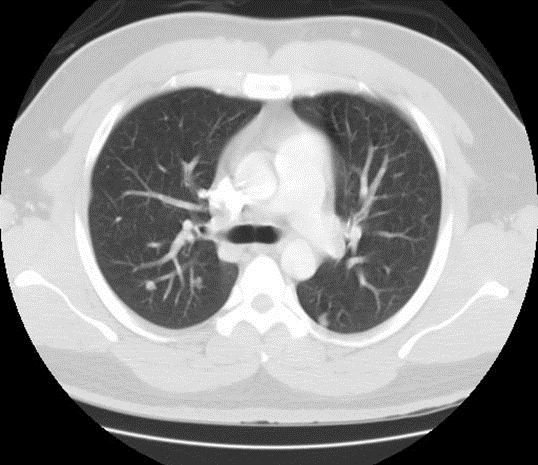

MRI of the brain showed extensive bilateral T2 hyperintense and peripherally enhancing foci within the cerebrum, cerebellum and extraocular muscles consistent with the vesicular stage of neurocysticercosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. MRI brain. Extensive bilateral T2 hyperintense and peripherally enhancing foci within the brain parenchyma and extraocular muscles consistent with the vesicular stage of neurocysticercosis (A). The scolex can be visualized within the cyst as a high intensity nodule giving the lesion a pathognomonic ‘hole-with-dot’ appearance (B).

Histopathology

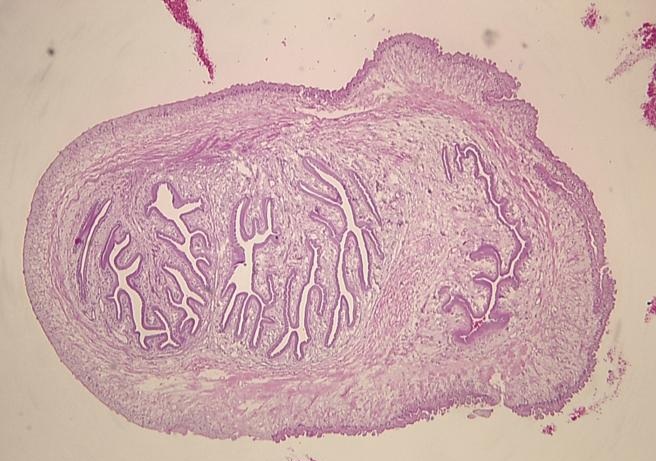

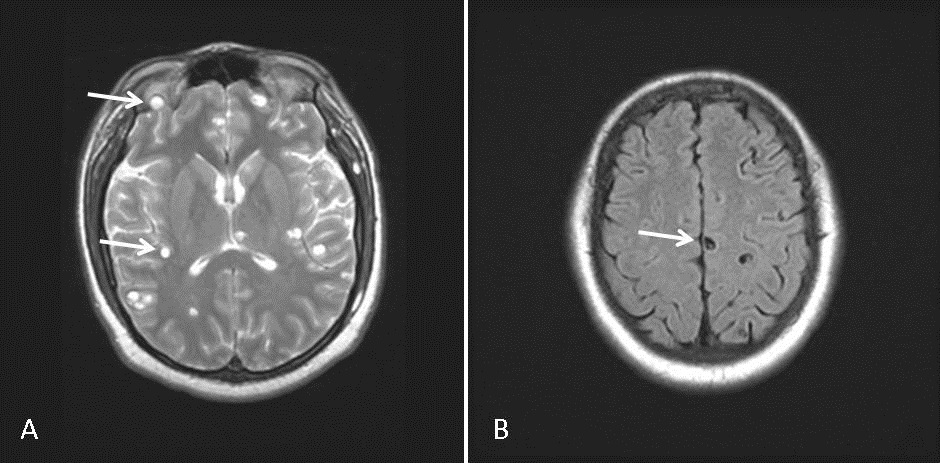

Bronchoscopy revealed normal airways with negative bronchoalveolar lavage. Histopathology from a needle core biopsy of a chest wall nodule revealed a cystic wall structure, consistent with cysticercosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Stained microsection of a chest wall needle core biopsy showing the cystic wall structure of cysticercosis. The wall consists of 3 layers: an outer or cuticular layer, a middle cellular layer and an inner fibrillary layer.

Percutaneous lung nodule biopsy demonstrated nonspecific necrotic granulomatous tissue.

Hospital Course

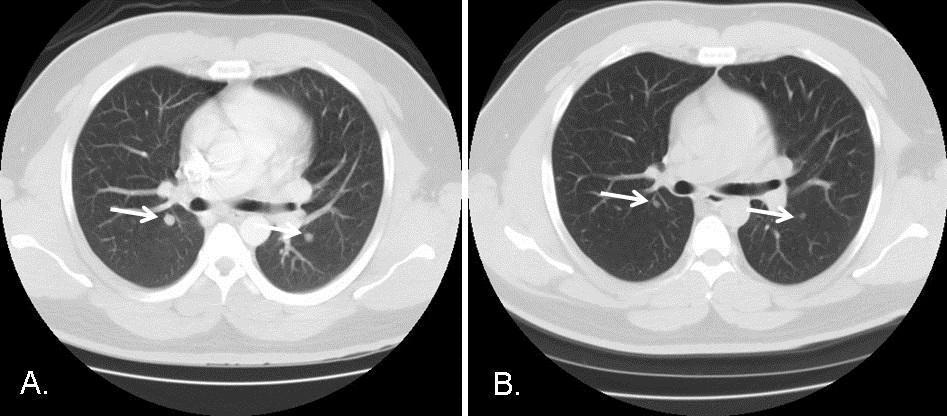

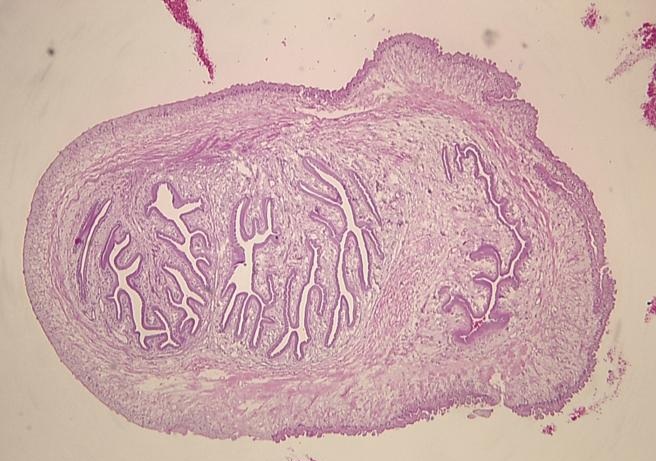

On the basis of neuroimaging and subcutaneous biopsy findings, a diagnosis of disseminated cysticercosis with pulmonary involvement was made and the patient was started on a 28-day course of albendazole therapy. One month follow-up revealed resolution of respiratory symptoms. Repeat CT chest, 53 days post-hospitalization revealed a regression in the magnitude of the pulmonary nodules, the largest now measuring 6mm in diameter (Figure 4).

Figure 4. CT scans of the chest, lung windows. Comparing Panel A with Panel B performed 53 days later reveals a reduction in the size of the bilateral pulmonary nodules (arrows) after a 28-day course of anti-parasitic therapy with albendazole.

Regression of the pulmonary nodules was consistent with the diagnosis of pulmonary cysticercosis, in line with previous reports (1).

Discussion

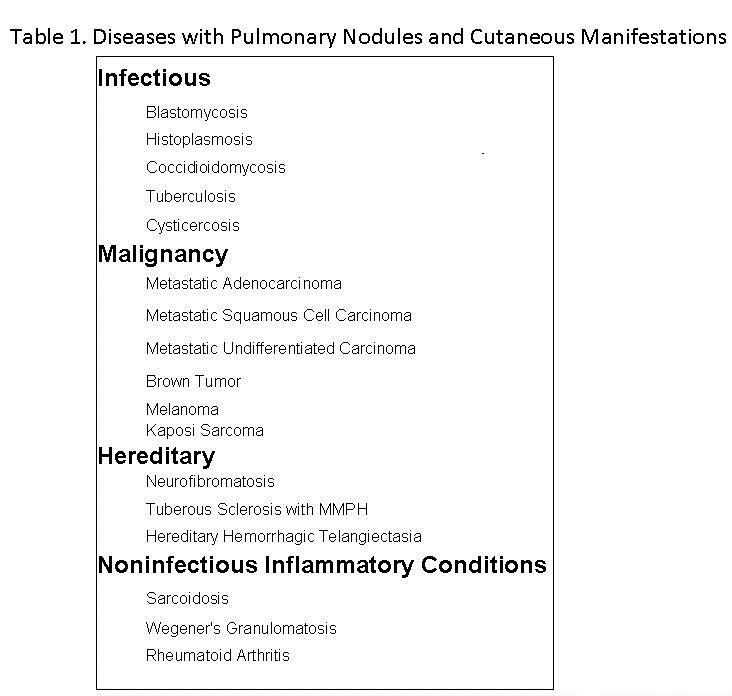

The differential diagnosis of multiple pulmonary nodules is large. A variety of pulmonary disorders may affect both cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues and the lung (Table 1).

The findings of extrapulmonary nodules in other organ systems and biopsy of nodules can help establish the diagnosis or limit the differential diagnosis of multiple pulmonary nodules when thoracic image findings are nonspecific.

Cysticercosis refers to infection by the larval stage of the pork tapeworm, Taenia solium. Cysticercosis has emerged as a cause of severe neurologic disease in the United States that primarily affects immigrants from endemic regions. Within the US cases of cysticercosis are mostly reported in CA, IL, OR, TX, and NY. Disseminated cysticercosis is an uncommon manifestation of the disease with fewer than 50 cases described worldwide, most occurring in India. Even more unusual is involvement of the lung parenchyma (1), with less than 10 cases described in literature. To our knowledge, this is only the second case of disseminated cysticercosis with pulmonary involvement described in North America (2).

Cysticercosis most commonly affects the central nervous system (neurocysticercosis). However, when disseminated, it frequently involves the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Cutaneous cysticerci are often a clue to the involvement of internal organs. In one case series of thirty-three patients with disseminated cysticercosis, sixteen (48%) presented with cutaneous lesions (3). Detection of the parasite in a biopsy specimen of skin nodules will aid in the diagnosis of disseminated cysticercosis and may prevent further, unnecessary diagnostic tests from being performed.

Sarcoidosis is a common cause of pulmonary nodules with extrapulmonary manifestations. Recent reports have characterized the development of sarcoidosis in patients receiving pegylated interferon alfa and ribavirin for the treatment of Hepatitis C (4). In sarcoidosis, there is a predominance of Th1 type immune response, while Th2 lymphocytes are relatively inactivated in granuloma formation (5). Both IFN-α and ribavirin stimulate the differentiation of Th1-type lymphocytes while inhibiting the activation of Th2-type lymphocytes (6). Together, this combination therapy works in favor of granuloma formation and the activation/re-activation of sarcoidosis. The temporal association between the initiation of therapy for hepatitis C and the onset of symptoms in the above case raised concern for drug induced sarcoidosis. However, sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion and the specific identification of the parasite in the subcutaneous nodule biopsy makes sarcoidosis unlikely.

The skin is the most common site for disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Multiple pulmonary nodules with cutaneous lesions in an individual living in Arizona should raise suspicion for coccidioidomycosis. The above patient had a negative coccidioidomycosis work-up and biopsies were not consistent with that of coccidioidomycosis.

Conclusion

Pulmonary cysticercosis is an uncommon manifestation of cysticercosis. The differential diagnosis of multiple pulmonary nodules is large. However, the diagnosis may be aided by recognizing extrapulmonary lesions that are often associated with lung diseases. Disseminated cysticercosis with pulmonary involvement should be suspected in any patient presenting with multiple pulmonary nodules who is an immigrant from an endemic region or an individual who has resided in one of the States where cysticercosis is most commonly encountered.

References

- Mamere AE, Muglia VF. Disseminated Cysticercosis With Pulmonary Involvement. J Thorac Imaging 2004;19:109-111.

- Walts AE, Nivatpumin T, Epstein A. Pulmonary cysticercus. Mod Pathol 1995;8:299-302

- Arora PN, Sanchetee PC, Ramakrishnan KR, Venkataram S. Cutaneous, mucocutaneous and neurocutaneous cysticercosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1990;56:115-8

- Ramos-Casals M, Mana J, Nardi N et al. Sarcoidosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: analysis of 68 cases. Medicine 2000;84:69-80.

- Rodríguez-Lojo, M. Almagro, J. M. Barja, et al., “Subcutaneous Sarcoidosis during Pegylated Interferon Alfa and Ribavirin Treatment for Chronic Hepatitis C,” Dermatology Research and Practice, vol. 2010, Article ID 230417, 2010. doi:10.1155/2010/230417

- Tam RC, Pai B, Bard J, et al. Ribavirin polarizes human T cell responses towards a type 1 cytokine profile. J Hepatol 1999;30:376-382.

Address inquires to: Christopher.Strawter@mihs.org

Reference as: Strawter C, Quiroga P, Zaidi S, Ardiles T. Pulmonary nodules with cutaneous manifestations: A case report and discussion. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2012;4:116-21. (Click here for a PDF version of the manuscript)

Friday, May 4, 2012 at 3:39PM

Friday, May 4, 2012 at 3:39PM