Congenital Bronchial Atresia: A Case Report with Radiographic and Pathologic Correlation

Monday, September 26, 2011 at 3:50PM

Monday, September 26, 2011 at 3:50PM Lewis J. Wesselius, MD1

John R. Muhm, MD2

Henry D. Tazelaar, MD3

Departments of Pulmonary Medicine1, Radiology2, and Laboratory Medicine- Pathology3, Mayo Clinic Arizona, 13400 East Shea Boulevard, Scottsdale, AZ 85259

Reference as: Wesselius LJ, Muhm JR, Tazelaar HD. Congenital bronchial atresia: a case report with radiographic and pathologic correlation. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2011;3:64-9. (Click here for a PDF version)

Abstract

Bronchial atresia is a rare congenital disorder characterized by localized atresia or stenosis of a segmental bronchus. Imaging features typically include mucus impaction in distal airways associated with regional lung hyperlucency. Pathologic features of bronchial atresia have been rarely been reported. This case demonstrates CT features of this disorder as well as the unusual finding of increased lung uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose on PET scan. This finding led to a surgical lung biopsy to exclude infectious or neoplastic disorders. This case provides radiologic-pathologic correlation in a patient with congenital bronchial atresia and demonstrates that localized, mildly increased uptake on PET scan be associated bronchial atresia.

Case Presentation

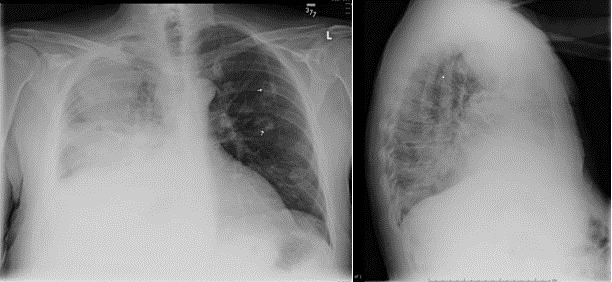

A 35-year-old woman was referred for evaluation of an abnormal thoracic CT scan. An abnormality was noted on a routine chest radiograph 2 years previously, and thoracic CT reportedly showed an “infiltrate” in the right upper lobe. Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage performed 1 year previously was reportedly negative. The patient was asymptomatic and denied any cough, fever or shortness of breath. On physical examination the patient was afebrile and the chest examination was within normal limits. She had a normal complete blood count and serologic studies for coccidioidomycosis were negative. A recent chest radiograph (Figure 1) and thoracic CT (Figure 2) performed at the referring medical center demonstrated abnormalities in the right upper lobe, without clear visualization of the posterior segment right upper lobe bronchus. Repeat bronchoscopy was performed which and reportedly demonstrated a patent right upper lobe posterior segmental bronchial orifice, although limited visualization into the airway was noted. Microbiologic studies and cytologic examination of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were negative.

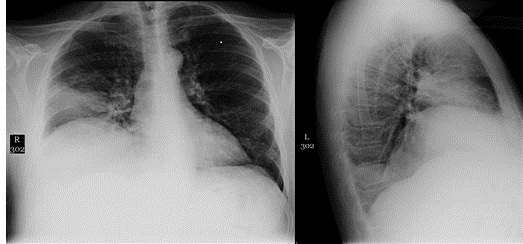

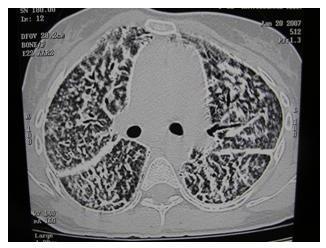

Figure 1: Chest radiograph performed one month prior to presentation shows small nodular opacities of indeterminate etiology in the right upper lung.

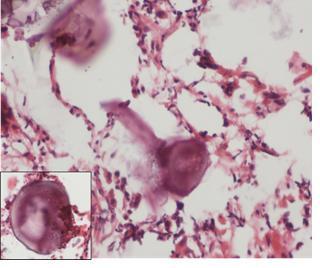

Figure 2: Thoracic CT shows atresia of the central portion of the right upper lobe posterior segment bronchus (arrow). In the right upper lobe posterior segment, peripheral to the atretic bronchus, numerous irregular opacities resulting from dysplastic bronchi filled with mucus are noted. The hypoattenuating areas in the right upper lobe posterior segment represent hypoperfused secondary pulmonary lobules resulting from the obstructed, dysplastic bronchioles.

Subsequent Clinical Course

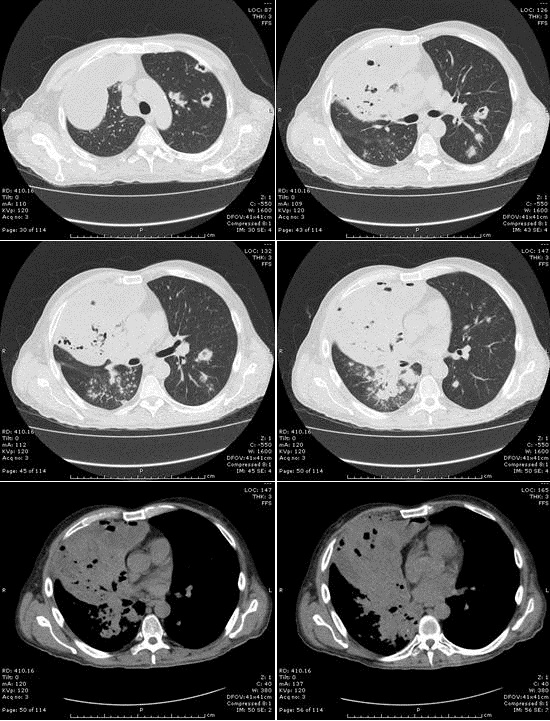

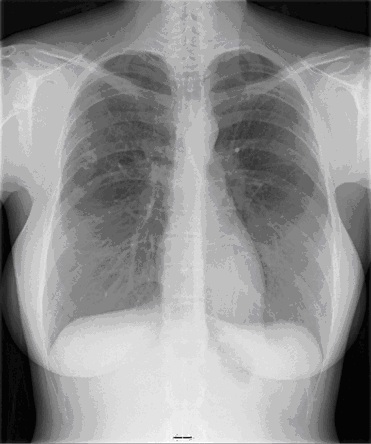

Subsequent 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG- PET, Figure 3) scan performed at the outside medical center showed hypermetabolism within the right upper lobe, with a standard uptake value (SUV) of 2.9.

Figure 3: Image from Coronal FDG-PET shows areas of mild-to-moderate increased uptake (SUV 2.2) in the posteromedial aspect of the right upper lobe.

The finding of elevated FDG uptake on PET scan, as well as an increase in the extent of CT abnormalities, raised clinical concern for an undiagnosed infectious process or low-grade malignancy. The patient subsequently underwent a thoracoscopic lung biopsy at the outside institution to exclude those possibilities.

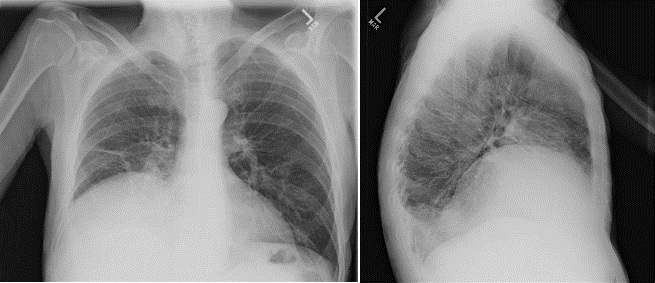

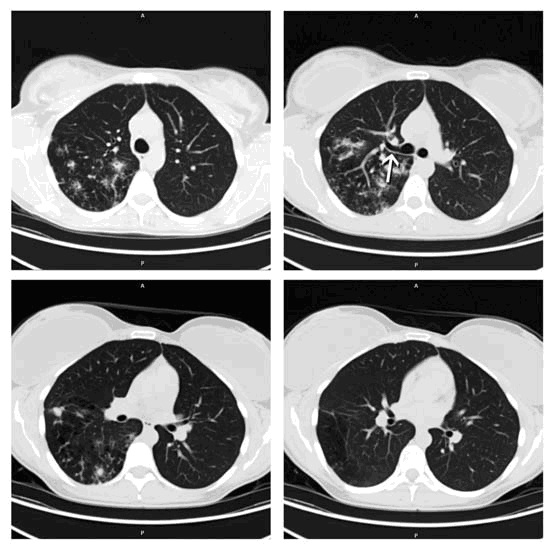

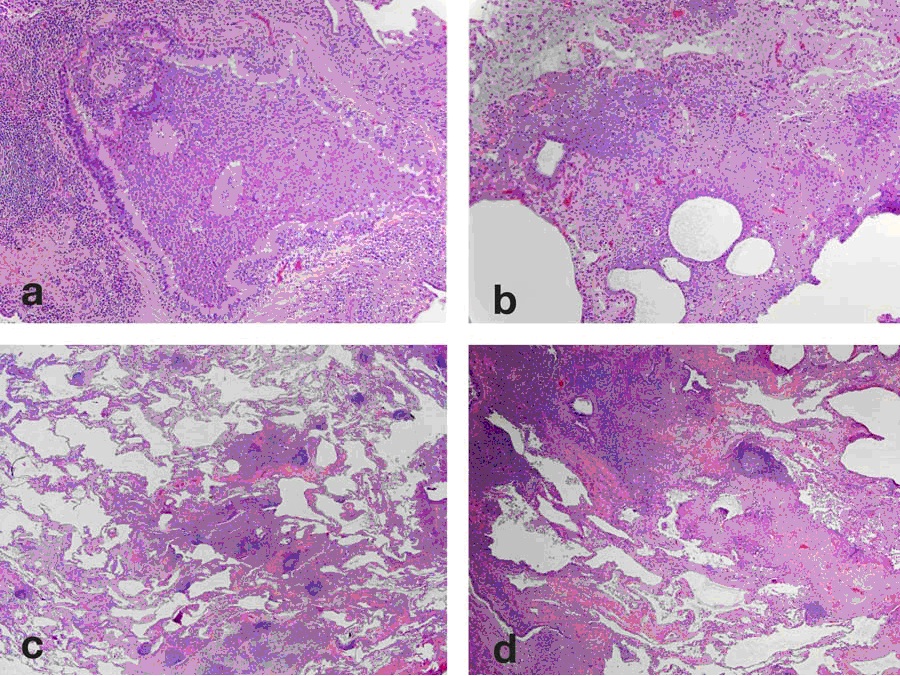

Further radiology review of the lung CT scan was concurrently requested by the referring physician and the radiographic features of bronchial atresia involving the posterior segment of the right upper lobe were noted. There was a dysplastic bronchus supplying the posterior segment of the right upper lobe, filled with mucus, and associated with evidence of hypoperfusion of that segment. Review of the tissue obtained at lung biopsy (Figure 4) demonstrated mucus impaction in small airways, consistent with changes secondary to bronchial atresia. There was no evidence of active infection or a neoplastic process.

Figure 4: VATS biopsy specimen obtained from the right upper lobe. The biopsy shows a chronic bronchiolitis (a) with lymphoid hyperplasia and germinal centers (b.center). There is also prominent bronchiolectasis (c) with mucostasis in the airway lumen and extending into the surrounding lung (d).

Discussion

Bronchial atresia is an uncommon congenital tracheobronchial abnormality first described in 1953 and is characterized by stenosis of a segmental airway (1). The abnormality generally involves a single segment, although cases with mult- isegment involvement have been reported (2). The apical-posterior segment of the left upper lobe is most frequently involved, followed by segments within the right upper, middle and lower lobes (3,4). This abnormality is frequently asymptomatic and is incidentally detected on chest radiography in 58% of cases (2). Patients may present, often in early adulthood, with symptoms of recurrent infections (21%), dyspnea (14%) and cough (6%). Cases associated with spontaneous pneumothorax have been reported (5).

The diagnosis of congenital bronchial atresia can generally be made from thoracic CT findings alone. Characteristic imaging findings include mucus impaction in dilated airways distal to the area of stenosis (6), typically associated with regional pulmonary parenchymal hyperlucency due to hypoperfusion, representing mosaic perfusion, resulting from obstructed dysplastic bronchi.

Bronchoscopy can be helpful to exclude competing diagnostic considerations and to exclude infectious processes. In some patients, segmental airway atresia or an obvious narrowing may be directly observed at bronchoscopy. However, the area of stenosis is not always visible at bronchoscopy (7). In our patient, the bronchoscopy did not clearly identify an area of segmental narrowing, although that finding was suggested by the CT scan (Figure 2).

FDG-PET (Figure 3), performed to evaluate for a possible undiagnosed infectious or malignant process, showed increased uptake in the areas of radiographic abnormality. However, subsequent VATS biopsy of the right upper lobe was negative for any infectious or neoplastic process. Increased uptake pulmonary parenchymal on FDG-PET scan is commonly seen in lung neoplasms and infections, but has also been reported in non-infectious inflammatory lung conditions, including sarcoidosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (8,9). There are prior case reports of localized pulmonary parenchymal uptake on FDG-PET scans performed in patients with benign airway disorders, including acute bronchitis and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (10,11). The finding of increased uptake on FDG-PET scan has not previously been reported in patients with congenital bronchial atresia. The specific reason for the localized uptake in the pulmonary parenchyma distal to the atretic bronchus in our patient is not certain. It is possible that local inflammation associated with mucostasis contributed to this finding as there was some evidence of interstitial inflammation noted on the surgical lung biopsy.

The lung biopsy obtained in this patient showed findings consistent with bronchial atresia including mucostasis in airways. The finding of mucostasis correlates with the CT findings of mucus impaction in dilated airways. Review of the literature indicated only one prior report of pathologic findings in patients with bronchial atresia (12). The findings in our case- respiratory bronchioles plugged with mucus- are consistent with those previously reported. Dilation of surrounding alveoli without evidence of destruction has also been previously reported, consistent with air-trapping.

Summary

Congenital bronchial atresia is an uncommon disorder that can present with a specific pattern on thoracic CT performed on asymptomatic patients or patients with respiratory symptoms of recurrent infections, dyspnea and cough. Bronchoscopy can be helpful to exclude other diagnostic considerations and may demonstrate evidence of segmental bronchial stenosis, although the area of stenosis may not be evident in all cases. Our patient presented with the unusual finding of mildly increased, localized uptake of FDG-PET scan, a finding previously unreported. Lung biopsy confirmed pathologic features consistent with bronchial atresia, including airway dilatation and terminal bronchial mucus impaction.

References

- Ramsey BH, Byron FX. Mucocele, congenital bronchiectasis and bronchogenic cyst. J. Thoracic Surg 1953;26:21-30.

- Jederlinic PJ, Sicilian L, Baigelman W, et al. Congenital bronchial atresia – a report of 4 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine 1986;65:73-83.

- Meng RL, Jensik RJ, Faher LP, Matthew GP, Kittle CF. Bronchial atresia, Ann Thoracic Surg 1978;25:184-192.

- Muller NL, Fraser RS, Colman N, Pare P. Developmental and hereditary lung disease. In: Radiologic diagnosis of diseases of the chest. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2001: 125-128.

- Berkman N, Bar-Ziv J, Breuer R. Recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax associated with bronchial atresia. Resp Med 1996;90:307-309.

- Matsushima H, Takoyanagi N, Satoh M, et al. Congenital bronchial atresia: radiologic findings in nine patients. J Comp Assist Tomog 2002;26:860-864.

- Ward S. Morcos SK. Congenital bronchial atresia – presentation of three cases and a pictoral review. Clin Radiol 1999;54:144-148.

- Brudin LH, Balind SO, Rhodes CG, et al. Fluorine-18 deoxyglucose uptake in sarcoidosis measured with positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med 1994;21:297-305.

- Groves Am, Win T, Screaton NJ, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and diffuse parenchymal lung disease: implications from initial experience with18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med 2009;50:538-545.

- Kicska G, Zhuang H, Alavi H. Acute bronchitis imaged with F-18 FDG positron emission tomography. Clin Nucl Med 2003;28:511-512.

- Nakajima H, Sawaguchi H, Hoshi S, Nakajimo S, Tohda Y. Intense 18F- fluorodeoxyglucose uptake due to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Jap J. Allergology 2009;58:1426-32.

- Gipson MG, Cummings KW, Hurth KM. Bronchial atresia Radiographics 2002;29:1531-1535.