S Keerti kumar S

B Maharani, MD

R Venkateswara Babu, MD

M Prakash, MD

Departments of Pharmacology, Respiratory Medicine and Community Medicine

Indira Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute

Puducherry, India

Abstract

Introduction: Medication adherence is a major determinant for the success of therapy among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. The research objectives of the present study were to assess the adherence to prescribed medications and its association with quality of life among COPD patients, to determine the major factors that influence the medication adherence and to assess patient’s knowledge on COPD and its relation to medication adherence.

Methods: It was a hospital based cross-sectional study. Patient demographic characteristics, smoking and alcoholic status, severity grading of COPD, concomitant disease, affordability of patients to medication, patient knowledge on COPD (Knowledge Questionnaire), adherence to medication and inhaler, major factors influencing adherence, disease control and quality of life (COPD Assessment Test) were recorded.

Results: Most of the patients were non-smokers and patients exposed to occupational air pollutants was high. Complete adherence to prescribed medication was found among 47% (MAS Score 6) of the participants and 81% of the participants were partially adherent (MAS score, range of 1-6). Highly adherent group was found to have high CAT score which was statistically significant. (P=0.020). Major factors for medication non-adherence were forgetfulness (82.5%) and symptomatic relief of illness (12.5%). There was no statistically significant association between individual knowledge questions and medication adherence except the question “COPD medicines prevent the disease from getting worse” (P=0.021).

Conclusion: There was a statistically significant association between medication adherence and quality of life. Appropriate health education should be implemented for improving patient awareness and medication adherence.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common, preventable and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases (1). In industrialized and developed countries, it is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality (2). The World Health Organization predicts that COPD will become the third leading cause of death by 2030 (3). Currently, various drugs like β2 agonist (long and short acting), inhalational anticholinergics, inhalational corticosteroids and methyl xanthines are utilized to prevent, control the symptoms and also to minimize the occurrence of COPD exacerbations (4,5).

The main factor that determines the success of therapy appears to be medication adherence. The medication adherence rates among COPD patients in clinical trials has been found to be 70 to 90% but in clinical practice it was very low accounting for only 10 to 40% (6-11). Non-adherence to therapy may lead to poor health and increased morbidity and health care cost, which in turn alters the quality of life (12). There appear to be few studies in India on medication adherence among COPD patients. This study is novel in assessing the adherence to drug therapy and its relation to quality of life, patients’ knowledge on COPD and its relationship to medication adherence and major factors influencing the medication adherence among COPD patients attending the tertiary care Institute in one of the Union Territory in India.

Methods

Study design and setting: A cross-sectional study was conducted in a tertiary care hospital. The study center was a referral hospital for nearby primary and secondary care hospitals and a separate COPD clinic was run every week for treating COPD patients. The study was conducted for a period of 6 months after obtaining Institutional Ethics Committee clearance.

Study Population: Eligible patients were those referred and diagnosed with COPD by FEV1 and categorized according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) staging and were receiving medications (with no alterations in treatment regimen during the past 3 months). Since the study was on medication adherence, all the COPD patients attending the outpatient department during the study period were considered. Patients with a history of asthma, allergic rhinitis, hospitalization for COPD exacerbation in last 3 months, heart failure or serious liver disease or renal failure or acute coronary syndrome patients and mental illness patients were excluded.

Data Collection: The patients satisfying the inclusion criteria were interviewed after obtaining their written informed consent. Patient demographic details, smoking and alcoholic status, occupational exposure to air pollutants, age at diagnosis of COPD, duration of COPD, concomitant disease, affordability of patients to medication were recorded. Post-bronchodilator FEV1 was measured with spirometry and grading of COPD was done following Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) staging (13).

Questionnaires used: Patient knowledge on COPD was assessed using COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (COPD-Q) (14). It is a valid, reliable and low-literacy tool to assess COPD related knowledge in patients. Adherence to medication and inhaler was evaluated by using Medication Adherence Scale (MAS) and Medication adherence report scale (MARS) (15,16). Reasons for non-adherence (missing or discontinuing the dose) were also obtained from the patients. Disease control and quality of life was assessed by using COPD assessment Test (CAT) (17). CAT score varies with changes in treatment and exacerbations of disease due to poor adherence. CAT scoring ranges between 0 and 40. Score of

> 30 - very high impact of COPD on patients

>20 - high impact of COPD on patients

10 to 20 - medium impact of COPD on patients

<10 - low impact of COPD on patients

5 - very low impact of COPD on patients

Statistical Analysis: Data entry was done in MS Excel 2010. Data was analyzed using professional statistics package EPI Info 7.0 version for windows. Descriptive data was represented as mean ± SD, median and interquartile range for numeric variables, percentages and proportions for categorical variables. Appropriate tests of significance were used depending on nature & distribution of variables like Chi square test, student’s t test for categorical variables. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Spearman’s correlation test was used to find out the relationship between medication adherence and quality of life.

Results

During the six months study period, 157 COPD patients were contacted. Out of the 157 patients, 19 patients refused to participate in the study, 5 patients were not able to answer appropriately and 42 patients had not satisfied the inclusion criteria. A total of 91 patients completed the study and gave complete responses to the questionnaire.

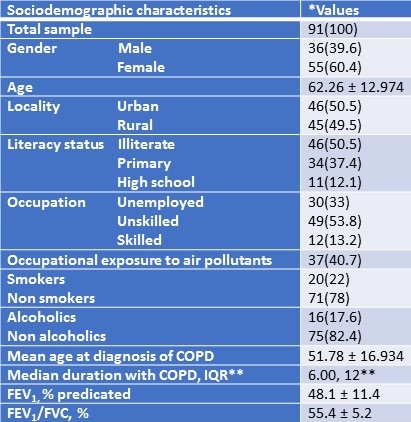

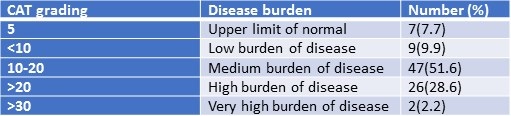

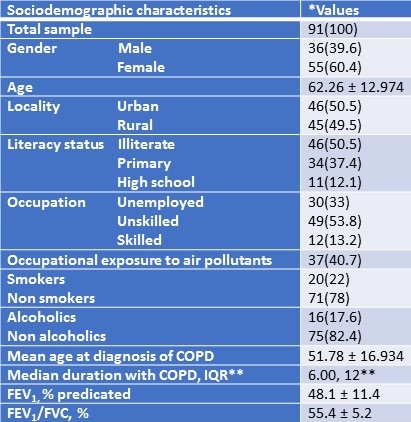

Sociodemographic characteristics of the patients were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants.

Most of the patients were non-smokers and patients exposed to occupational air pollutants was high. Based on GOLD staging of severity of COPD, 14% were graded as mild, 63% were graded as moderate, 20% were graded as severe and 3% of patients had very severe form of COPD. Concomitant diseases like diabetes, hypertension and hyperthyroidism was found in 74.7% of the participants. Nearly 50% of the participants belong to very low socioeconomic status as per Modified Prasad Classification and medication cost was affordable only by 24.2%.

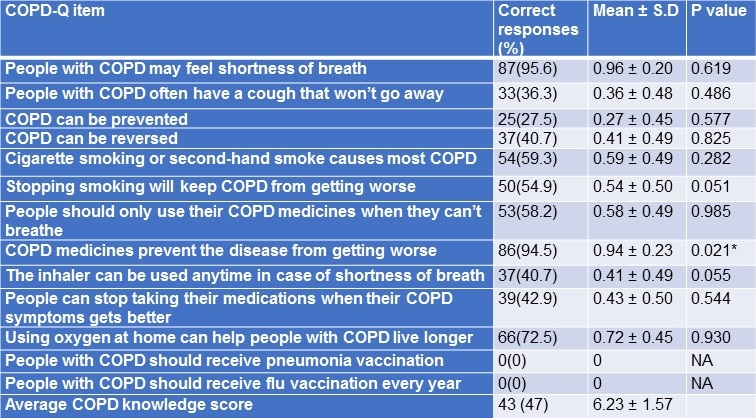

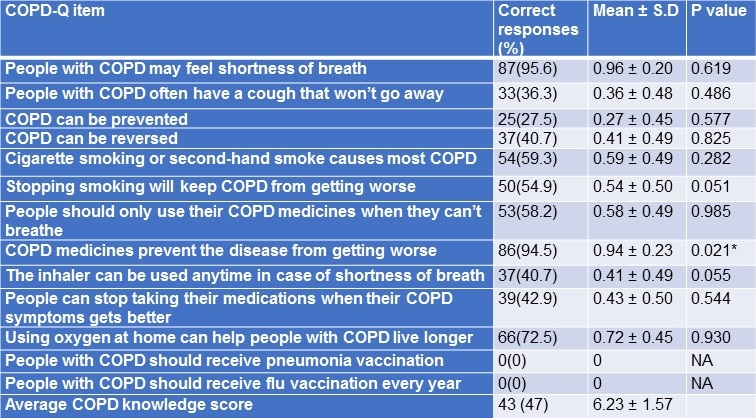

Patient responses to COPD – Knowledge Questionnaire (COPD-Q) and its relation to medication adherence were summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. COPD Knowledge Questionnaire responses and its relation to medication adherence among study participants.

*p<0.05 - statistically significant.

There was no statistically significant association between individual knowledge questions and medication adherence except the question “COPD medicines prevent the disease from getting worse” (P=0.021). Average COPD-knowledge score was 6.23 ± 1.57.

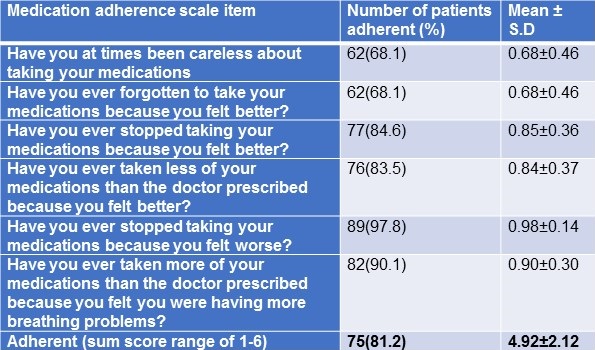

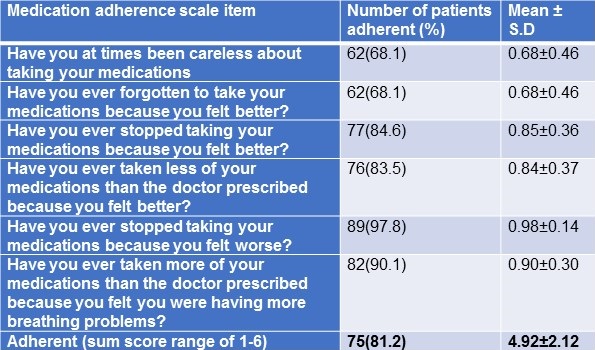

Responses to medication adherence scale were summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Responses to COPD medication adherence.

The adherent sum score ranged between 1-6, 43 (47%) participants who had a sum score of 6 were fully adherent to prescribed medications, 27 (30%) participants had a sum score of 5 and others had a sum score of 1-4 were partially adherent to prescribed medications. The overall medication adherence (range 1-6) among the participants was 81%.

Inhalational medications were used only by 43 (47.3%) patients. Responses to adherence to inhaled medications were summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Responses to inhalational medication adherence.

MARS sum score was 23.55±3.95. Higher score indicates higher self-reported adherence. MARS sum score ranged between 5-25. Out of 43 patients, 39 (91%) had the sum score in the range of 21-25.

The common reasons for medication non-adherence were forgetfulness (82.5%), symptomatic relief of illness (12.5%), 10% responded that medicines got exhausted and 2.5% reported that it was socially inconvenient to take the medications.

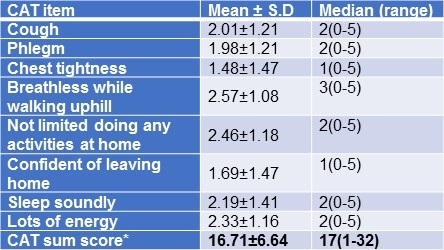

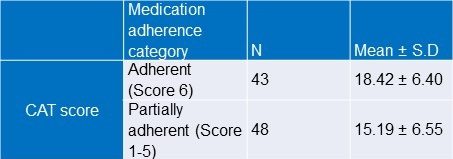

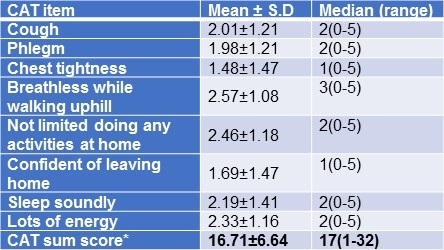

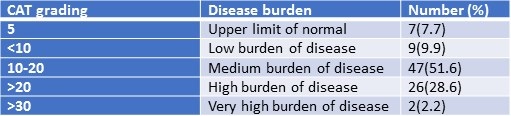

CAT score of the patients and grading were summarized in Tables 5 and 6.

Table 5. COPD Assessment Test (CAT) – Individual item responses.

Table 6. Categorization of study participants based on CAT Score.

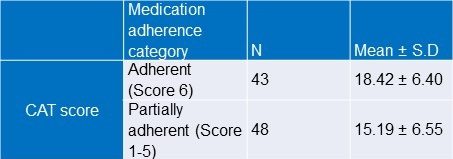

There was a statistically significant difference between adherent and partially adherent groups with respect to CAT score of the participants (Student’s t test; p value=0.020).

Highly adherent group was found to have high CAT score. (Table 7).

Table 7. Association between medication adherence score and CAT score.

Student’s t test; p value=0.020.

There was a statistically significant weak positive correlation (r=0.246) between medication adherence sum and CAT score.

Discussion

The patients in the present study had adherence to the medication at 47%. The percentage of adherence was less than the studies conducted in Hungary (58.2%) and Nepal (65%) (18,19). Although complete adherence was less than 50%, majority of the participants were partially adherent to the medications which was at 81% (Table-3). The most common cause for non-adherence was forgetfulness (82.5%). The percentage was very high when compared to other studies in which forgetfulness accounted for about 50% (15,19).

There was a statistically significant association between medication adherence score and the CAT score similar to the study done by Kocakaya et.al. (20). The study had revealed better the adherence, better the quality of life. Though there is weak positive spearman’s correlation which was statistically significant, it may not be clinically significant. This can be overcome by increasing the sample size. Only 43 participants used inhalational medications and there was higher self-reported adherence to inhalational medications. That data is similar to a study done by Tommelein et al. (16).

In the tertiary care Institute where the study was conducted, patients with moderate and severe symptoms alone were advised to purchase inhaler and during inhaler introduction they were properly trained on how to use the inhaler. Further, compliance to the inhalational medications were checked during each follow-up. Since moderate to severe symptomatic patients were comfortable with inhalational medications, there was high degree of adherence to inhalational medications.

The patient’s COPD knowledge score was 6.23 ± 1.57. It was less when compared to the study done by Ray SM., et al. (7.6 ± 2.1) (14). Awareness of the patients on smoking and its association with COPD, reversal of COPD with quitting of smoking was only around 50% but comparable to prior studies (14). The percentage of COPD patients with smoking was only 22%. The results were similar to the study done by Mahmood T et.al., in which the percentage of nonsmokers with COPD was higher when compared to smokers with COPD (21). It was interesting to note that 100% of the participants were not aware about the importance of flu and pneumonia vaccination. It may be because of poor literacy rate and lack of awareness among the participants.

The results of our study are not surprising and consistent with prior studies. However, sociodemographic factors affect compliance. To our knowledge this is the first study to show the association between adherence and quality of life in COPD in a unique Indian population.

Conclusion

The study showed a statistically significant association between medication adherence and quality of life. Further studies evaluating the impact of education on medication adherence and quality of life are needed.

References

- Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report. GOLD Executive Summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(5):557–82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viegi G, Scognamiglio A, Baldacci S, Pistelli F, Carrozzi L. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Respiration. 2001;68:4–19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2017 Dec 28]. Available from: http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/en/ (accessed 6/18/19)

- Toy EL, Beaulieu NU, McHale JM, et al. Treatment of COPD: Relationships between daily dosing frequency, adherence, resource use, and costs. Respir Med. 2011;105(3):435–41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazzola M, Dahl R. Inhaled Combination Therapy with Long-Acting β2-Agonists and Corticosteroids in Stable COPD. Chest. 2004;126(1):220–37. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rand CS, Nides M, Cowles MK, Wise RA, Connett J. Long-term metered-dose inhaler adherence in a clinical trial. The Lung Health Study Research Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:580–8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesten S, Flanders J, Serby CW, Witek TJ. Compliance with tiotropium, a once daily dry powder inhaled bronchodilator, in one-year COPD trials. Chest. 2000;118:191s– 192s.

- Van Grunsven PM, Van Schayck CP, Van Deuveren M, Van Herwaarden CL, Akkermans RP, Van Weel C. Compliance during long-term treatment with fluticasone propionate in subjects with early signs of asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): results of the Detection, Intervention and Monitoring Program of COPD and Asthma (DIMCA) Study. J Asthma. 2000;37:225–34. [PubMed]

- Krigsman K, Nilsson JL, Ring L. Refill adherence for patients with asthma and COPD: comparison of a pharmacy record database with manually collected repeat prescriptions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:441–8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender BG, Pedan A, Varasteh LT. Adherence and persistence with fluticasone propionate/salmeterol combination therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:899-904. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breekveldt-Postma NS, Gerrits CMJM, Lammers JWJ, Raaijmakers J a. M, Herings RMC. Persistence with inhaled corticosteroid therapy in daily practice. Respir Med. 2004;98(8):752–9. [PubMed]

- Montes de Oca M, Menezes A, Wehrmeister FC, et al. Adherence to inhaled therapies of COPD patients from seven Latin American countries: The LASSYC study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0186777. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2019 report. Available at: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GOLD-2019-v1.7-FINAL-14Nov2018-WMS.pdf (accessed 6/18/19).

- Ray SM, Helmer RS, Stevens AB, Franks AS, Wallace LS. Clinical utility of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease knowledge questionnaire. Fam Med. 2013;45(3):197–200. [PubMed]

- Dolce JJ, Crisp C, Manzella B, Richards JM, Hardin JM, Bailey WC. Medication adherence patterns in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 1991;99(4):837–41. [PubMed]

- Tommelein E, Mehuys E, Van Tongelen I, Brusselle G, Boussery K. Accuracy of the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS-5) as a quantitative measure of adherence to inhalation medication in patients with COPD. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(5):589–95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, Wiklund I, Chen WH, Kline Leidy N. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:648-654. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agh T, Inotai A, Meszaros A. Factors Associated with Medication Adherence in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Respiration. 2011;82(4):328–34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha R, Pant A, Shakya Shrestha S, Shrestha B, Gurung RB, Karmacharya BM. A Cross-Sectional Study of Medication Adherence Pattern and Factors Affecting the Adherence in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2015;13(49):64–70. [PubMed]

- Kocakaya D, Yıldızeli ŞO, Arıkan H, et al. The relationship between symptom scores and medication adherence in stable COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(61):PA1062.

- Mahmood T, Singh RK, Kant S, Shukla AD, Chandra A, Srivastava RK. Prevalence and etiological profile of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in nonsmokers. Lung India. 2017;34(2):122–6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: kumar S KS, Maharni B, Babu RV, Prakash M. Adherence to prescribed medication and its association with quality of life among COPD patients treated at a tertiary care hospital in Puducherry – a cross sectional study. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2019;18(6):157-66. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc021-19 PDF

Sunday, September 1, 2019 at 8:00AM

Sunday, September 1, 2019 at 8:00AM